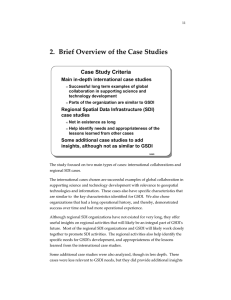

4. The Case Studies Detailed Descriptions of the Case Studies

advertisement