How to Defuse Iran’s Nuclear Threat Spring 2012

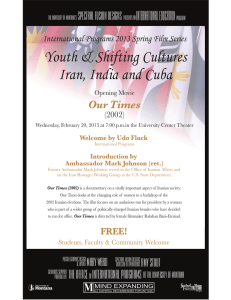

advertisement