@ Environment Harvard Hope in Copenhagen?

advertisement

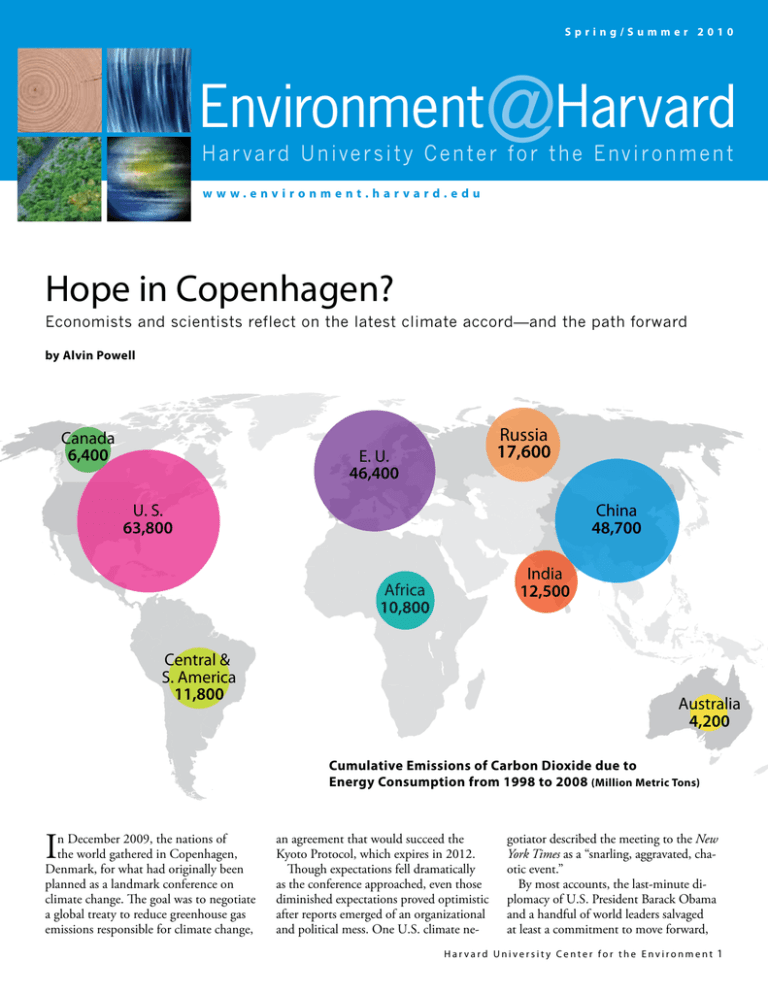

Spring/Summer 2010 Environment @Harvard H a r v a rd U n i ve r s i t y C e n t e r f o r t h e E nv i r o n m e n t www.environment.harvard.edu Hope in Copenhagen? Economists and scientists reflect on the latest climate accord—and the path forward by Alvin Powell Canada 6,400 Russia 17,600 E. U. 46,400 China 48,700 U. S. 63,800 India 12,500 Africa 10,800 Central & S. America 11,800 Australia 4,200 Cumulative Emissions of Carbon Dioxide due to Energy Consumption from 1998 to 2008 (Million Metric Tons) I n December 2009, the nations of the world gathered in Copenhagen, Denmark, for what had originally been planned as a landmark conference on climate change. The goal was to negotiate a global treaty to reduce greenhouse gas emissions responsible for climate change, an agreement that would succeed the Kyoto Protocol, which expires in 2012. Though expectations fell dramatically as the conference approached, even those diminished expectations proved optimistic after reports emerged of an organizational and political mess. One U.S. climate ne- gotiator described the meeting to the New York Times as a “snarling, aggravated, chaotic event.” By most accounts, the last-minute diplomacy of U.S. President Barack Obama and a handful of world leaders salvaged at least a commitment to move forward, Harvard University Center for the Environment 1 “Copenhagen illustrated problems with the process… . About 190 countries are talking, when 20—counting the EU as one—account for 80 percent of global emissions.” Pratt professor of business and government Robert N. Stavins of the Harvard Kennedy School directs the Harvard Environmental Economics Program and the Harvard Project on International Climate Agreements. with most participating nations “noting” a short, nonbinding accord, providing at least some guidelines for action and cause for hope. The months since have allowed time for reflection on Copenhagen and on what meaningful action might come next, perhaps as soon as the next such meeting, scheduled for Cancun, Mexico in December 2010. To better understand where these complex issues stand today, the Harvard University Center for the Environment (HUCE) posed questions on the Copenhagen meeting, its implications, in this issue Hope in Copenhagen? Economists and scientists assess the successes and failures of the Copenhagen climate conference—and the way forward. 3 Mostafavi about the intersection of sustainability and design principles. 13 Food in the Balance In the global battle against hunger, climate change introduces a host of new uncertainties. Letter from the Director 10 Re-envisioning Sustainability as a Design Art HUCE director Dan Schrag talks with Graduate School of Design dean Mohsen 2 and the best way forward to a handful of HUCE-affiliated faculty members involved in climate change science and policy. Participants include: Robert Stavins, Pratt professor of business and government at the Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) and director of the Harvard Project on International Climate Agreements; Jeffrey Frankel, Harpel professor of capital formation and growth at HKS; Richard Cooper, Boas professor of international economics; James G. Anderson, Weld professor of atmospheric chemistry; Peter Huybers, assistant professor of earth and planetary sciences; Steven Wofsy, Rotch professor of atmospheric and environmental science; Michael McElroy, Butler professor of environmental studies; and HUCE director Daniel Schrag, Hooper professor of geology. Spring/Summer 2010 20 Implications of a Nuclear Renaissance Is nuclear power a viable source of energy for the future? Leading policy experts discuss the potential and the pitfalls. E@H: Would you characterize Copenhagen as a success? Robert Stavins: It would have been very unfortunate to achieve what some participants would have defined as “success” in Copenhagen. That would have been a signed international agreement, glowing press releases, and photo opportunities. The reason I say “unfortunate” is that there is only one possible agreement that would have met those characteristics. That would have been the Kyoto Protocol on steroids. In other words, more stringent targets for the Annex 1 countries—that’s the industrialized world; no meaningful action by the key emerging economies— China, India, Brazil, South Africa, Korea, Mexico, and a couple of others. That would have meant no emissions reductions globally. It also would have meant no ratification by the United States Senate, which would have been just like Kyoto—no real progress on climate change. There was political grandstanding and a lack of consensus. But at the last minute, quite dramatically, there were direct negotiations by key national leaders. This was virtually unprecedented because it’s usually people four levels down in the respective ministries that do the negotiations. That saved the conference from complete collapse and produced a significant political—not legal, but political—agreement that has been labeled the Copenhagen Accord. The accord takes a “portfolio of domestic commitments” approach—each country essentially commits to do what it has on the books domestically. It addresses two very important deficiencies of the Kyoto Protocol. One is it expands the coalition of meaningful commitments to include all the major emitters. And it expands the timeframe of action. So the Copenhagen accord has both good news and bad news. The good news Jeffrey Frankel, Harpel professor of capital formation and growth at the Harvard Kennedy School. is it provides real cuts on greenhouse gas emissions by all the major emitters. It establishes a transparent framework for evaluating countries’ performances. It initiates a substantial flow of resources to help poor, vulnerable nations carry out mitigation and adaptation. But there’s bad news. This is certainly not on track for a two degree centigrade, or a 450 parts per million (ppm) stabilization of CO2; but neither is any other policy, including a hypothetical Kyoto agreement on steroids. Jeffrey Frankel: My definition of progress is steps toward specific, credible commitments by a large number of countries. And in that sense, we actually had some good news. January 31 [2010] was the deadline under the Copenhagen Accord [to specify 2020 emissions targets] and 106 countries responded. Six big, emerging market countries set targets. Many of them are vague about the base year and they clearly resist saying this is a legal commitment— that’s obviously a limitation. The fact that they’re taking this seriously means that Obama’s personal breakthrough there on the last day may indeed lead somewhere. Richard Cooper: It was even worse than I expected it to be. I forecast two years ago that it would fail on substantive grounds. But the process is a throwback to 30 to 35 4 Spring/Summer 2010 years ago, which I think is sad for the international community. The G-77 [the group that represents developing world countries] is unable to negotiate. They get together ahead of time and decide what their demands are going to be. Once they decide what their position is going to be, they find it impossible to change, in a give-andtake sense. E@H: Some have argued that the United Nations process is unworkable and will never lead to a meaningful treaty. What are the prospects for progress going forward? Robert Stavins: Copenhagen illustrated problems with the process under the United Nations, particularly what’s called the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change [UNFCCC]. The first problem is the size. About 190 countries are talking, when the 20 largest economies—counting the EU as one— account for more than 80 percent of global emissions. Getting agreements among the full set of 190 countries on anything is difficult. What exacerbates that is that the U.N. culture tends to polarize factions, particularly the industrialized world versus the developing world. And then there’s the UNFCCC voting rule: unanimity is required. It was the lack of consensus on the Copenhagen Accord that led to it being noted, not adopted. So what are alternative institutions going forward? For the Harvard Project on International Climate Agreements, this is a major focus of research for the next six to nine months. One possible venue is the Major Economies Forum, an initiative launched by the Bush Administration as the Major Emitters Meeting. At the time, it was lambasted by environmental advocacy groups in the U.S. and Europe and by the E.U. as a diversion from the U.N. process. Wisely, the Obama administration recognized that it made a lot of sense, so they changed its name but kept it. Now it’s called the Major Economies Forum on Energy and Climate. And again, more than 80 percent of global emissions are covered by the 17 participating countries and regions. Another important potential forum going forward is the G-20. For the most part this has been finance ministers focusing on economic issues, but they think more broadly. It has the advantage of not being the creature of a single nation, which is a limitation of the Major Economies Forum. I believe it’s too early to write the obituary of the UNFCCC. For one thing, the Kyoto Protocol is going to be with us until 2012. Even more important is that it has a huge constituency, namely a majority of countries in the world—those are the developing countries. They would like everything to stay within the UNFCCC. In fact, they’d like to extend the Kyoto Protocol to become the exclusive focus of negotiations, for clear reasons that are in their self interest. But there is also international legitimacy for anything under the United Nations versus something that is the creation of a single nation. Jeff Frankel: Copenhagen was pretty discouraging. Progress is not possible solely in the U.N. framework because small member nations will obstruct the process. It isn’t just the one country-one vote thing; the WTO [World Trade Organization] is the same way. Technically, one country can hold it up but in that forum they never do. Because the big guys decide what the deal is, then the others take it or leave it and they usually take it. The important decisions can only be made by a small steering group, as has long been true with multilateral governance. And in the past it’s always the G-7. After years and years of talking about giving major emerging markets a voice and doing nothing, suddenly in 2009, the G-20 supplanted the G-7. That means they have representation for the first time. This is good news generally, that big emerging markets have been given a voice in world governance. Richard Cooper: For a variety of reasons, I think this forum cannot negotiate an agreement on climate change, but it’s not going to go away either, because the COP [Conference of Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change] are a regular part of the UNFC- “Two things have to happen. One, people have to get scared about climate change. And two, the strategy for dealing with it has to look a little bit cheaper and a little bit more doable.” CC process. So I think we need to have a negotiation outside and present them with the outcome of the negotiation. The negotiations have to be sensitive to the interests of the key developing countries and present it to them as, “this is what the deal is.” Dan Schrag: If out of Copenhagen and what President Obama did, we see a move to negotiations between a smaller number of key countries: the U.S., China, India, Brazil, the EU—the G-8 plus a handful— as opposed to all of the countries, I think that’s a positive move because it’s more likely to get something done. But at the same time no international treaty is going to be useful if people aren’t convinced that this is a serious problem. Nobody’s going to follow through on an agreement if they’re not actually concerned about the problem. It’s too expensive. Part of me feels like Copenhagen and the whole Kyoto process is almost irrelevant to the real activity around climate change, which is focused on industry, both in terms of alternative energy—bringing the cost down—and also things like carbon capture and storage, which means allowing us to still use fossil fuels and not pollute the atmosphere. Things are happening because companies are anticipating regulation. Coal plants: five years ago, six years ago there were 200 coal plants, roughly, in permitting. Two years ago, before the economy collapsed, they had almost all gone: banks weren’t taking those sorts of risks. In Detroit, there’s a competition [The Progressive X Prize to get super fuel efficient vehicles]. I have no idea whether they’ll succeed, but it’s a sign of work that’s being done that could be the foundation. There’s a similarity with the Montreal Protocol with CFC’s [ozone-depleting chlorofluorocarbons]. That was only agreed to after DuPont developed an alternative to CFCs. They complained they couldn’t do it until they came up with an alternative, then all of a sudden, the Montreal Protocol followed that. Two things have to happen. One, people have to get scared about climate change. And two, the strategy for dealing with it has to look a little bit cheaper and a little bit more doable. Right now it looks awfully expensive, it’s not clear who the winner is and you have some of the most powerful industries in the world campaigning against it. E@H: How will a meaningful agreement come about? Richard Cooper: First I think there should be bilateral conversations between the United States and China. We are the two elephants in the room and we’re not playing at the moment. We need to have serious, technical-level discussions—with political guidance of course—with the Chinese about what they’re willing to accept and what we’re willing to accept, what we think we can get through Congress. If it goes reasonably well, I think we could roll it out in the G-20. I don’t have any expectation that the U.S.-China discussions will produce something in time for the Seoul summit. But I think we should get the process going, because India is going to be a problem. The Indian leadership at the moment is outstanding, but they have the practical political problem of dealing with the Indian parliament which is at least as fractious as the U.S. Congress. This is a multi-year process, it’s not something that’s going to happen quickly. Robert Stavins: From a policy perspective, the cliché we often hear about the baseball season applies even more so to international climate policy: it is a marathon, not a sprint. International climate negotiations are best thought of as an ongoing process, perhaps somewhat like trade talks. Not a single task with a clear endpoint, whether Copenhagen, Cancun, whatever. E@H: What would we need to happen— scientifically or in the natural world—to change the game and really push things forward at this point? Dan Schrag: There are lots of things you can talk about: A big piece of ice breaking off of Antarctica. You can talk about heat waves, droughts, or floods. My fear is that none of them will ever be clear enough to enough people, especially when there’s a $300 million communications campaign paid for by the fossil fuel industry to confuse the issue. By the time people do get scared, it may be too late. That’s my worry. I think realistically you’re not going to see China and India and any other developing countries commit to serious reductions until they’re, quite frankly, just scared about the consequences of letting CO2 emissions continue. Right now, I Richard Cooper, Boas professor of international economics. don’t think they’re scared enough. And it’s clear that reducing emissions for them and reducing future emissions will limit their ability to grow their economies, and that’s the focus for them. So it’s a really tough problem. Richard Cooper: If we were to have three really blistering summers in a row, or a Harvard University Center for the Environment 5 serious drought in the plains states that people could analogize with Oklahoma in ‘33 and ‘34—the Dust Bowl—the U.S. dialogue on this would change radically. Honest climatologists will tell you that you cannot really attribute those events to climate change, but it would catch the public’s attention. Peter Huybers: My sense is we’re kind of in this for the long run. As time passes, we expect the climate to change and the evidence for that change to become increasingly obvious. Our understanding of ice dynamics is very thin. So an advance in our ability to predict what the cryosphere is doing James G. Anderson, Weld professor of atmospheric chemistry. [might have an impact], as would an understanding of the feedbacks associated with the carbon cycle in the Arctic tundra. It is my understanding there is a lot of uncertainty there. If history is a good indicator of what’s to come, we’re going to have incremental progress toward a treaty. Even at the rate of the IPCC reports, every five years—if you’re to measure that in an academic time scale, that’s the amount of time to produce a thesis. A thesis is likely to present some advance in our understanding, but nothing dramatic. E@H: Are you concerned about the pace of action? Are there possible ramifications for going slowly on a climate change treaty? 6 Spring/Summer 2010 “On our current trajectory, given political momentum…we’re headed for 600 to 700 parts per million in carbon dioxide. That carries us back 30 million years in history and at that point there was no ice at all in the northern hemisphere.” Jim Anderson: My feeling is that China is going to set the pace here, because they recognize they’re going to lose those key snowpack and glacial systems that provide critical parts of their water supply. It doesn’t matter if it’s 10 years or 50 years because the conclusion of any public policy…is exactly the same and you have to start taking very rapid corrective action right now. The minute they make that decision, they’ll go wholesale into making these [renewable] energy systems because they want to sell them internationally. So the United States has a couple of choices. We can look back at the twentieth century and “drill, baby, drill” and continue with the kind of public policy we had, or we can say, “If we don’t turn around and get moving very quickly and we don’t apply our technology…we’ll be buying all this stuff from China.” We’ve passed the point of stability— once you get above 350 ppm, which is 50 ppm in the rearview mirror, the glacial ice systems are no longer stable. From that perspective, we have a great deal of difficulty seeing a solution in any cutback in carbon dioxide unless it’s draconian. On our current trajectory, given political momentum…we’re headed for 600 to 700 parts per million in carbon dioxide. That carries us back 30 million years in history and at that point there was no ice at all in the northern hemisphere. There was a little bit forming in the Antarctic. It now becomes a question of how rapidly this process occurs. Dan Schrag: At what point will it be too late? The honest answer is we don’t know. We do know there are thresholds in the system: things like the breaking off of the Ross Ice Shelf, which would accelerate the demise of the Antarctic ice sheet; or the melting of the permafrost. But exactly where those thresholds are, we don’t know. My suspicion is we’re not going to know very well until it’s already happening. It’s possible that maybe 450 or 500 ppm is okay. Maybe it’s not catastrophic. So that’s a reason for optimism. Of course the problem is, if that’s not catastrophic, we’ll probably get to six or seven [hundred parts per million]. Steve Wofsy: Delaying isn’t a very good idea. The discussion shouldn’t just be about climate change. The discussion should be about the whole energy economy of the developed world. What we’re currently doing is unsustainable anyway, it’s bad for the environment, it’s costing us a lot of money, and a lot of things happen in the geopolitical framework that are pretty bad. The greenhouse gases we put in the atmosphere stay there for a very long time. They take a long time to work themselves out. Delay is dangerous and it is expensive. Jeff Frankel: My answer to this question has always been the same. There is nothing magic about this year. Or next year. Or any year. But the problem isn’t going to get any easier by postponing it. All the issues will be the same in the future…but just a little tougher. E@H: Once an agreement is struck, how long will it take before we are technically capable of transitioning to a lower-carbon energy system? Mike McElroy: I think we can make a difference on a timescale of 20 years, and it’s hard to go much faster than that. But we have to make that commitment if we’re going to get there. If we’re serious about it, we can have a different kind of energy system by 2030: a lot less coal, a lot more non-carbon sources. I think it’ll probably be wind, maybe solar will come along. I don’t think nuclear will grow very much. I think we’ll have a transportation system that will be more electrical: plug-in hybrids, maybe even all-electric cars. Natural gas may be a player in big vehicles, interstate trucks and buses. E@H: What would an alternative energy system look like, here or elsewhere around the globe? Jim Anderson: We’re endowed with wind power and solar thermal like no other nation on earth. The only other nation with wind power and solar thermal resources that can compare to ours is China. We have this massive resource, we could completely eliminate our import of petroleum products by switching to electrified vehicles and removing fuel oil we burn in our homes. We’d have no imports of petroleum at all. All of the energy would be generated here, all the jobs created by producing those systems and installing them would be here. Mike McElroy: The challenge for the United States is to reduce our dependence on coal in the electricity generating sector and to reduce oil in the transportation sector. There are two good reasons to do so. One is the climate issue. The second is the fact that even at $80 a barrel, we’re sending $375 billion a year to other countries. We have a number of alternatives to coal: nuclear, wind, solar. Natural gas is increasingly the fuel of choice, particularly with gas prices dirt cheap. We’ve done studies on what the potential is for wind in the U.S. as well as in China. The U.S. has abundant sources of wind, particularly in the Midwest down the central part of the country. You can generate that energy at prices that are currently competitive with alternatives. One of the problems with renewable sources of energy such as wind and solar is the intrinsic variability of the source, and the lack of ability to store electricity. There are three unconnected grids in the United States: East, West and Texas. We have access to the data on hourly electricity demand in the Texas region for the last few years. So what we’re doing is asking how you would realistically integrate wind into that system, and what are the problems and costs associated with that? As you go to more wind, the problem you confront is there will be times of the year—in the winter, at night—when there will be more electricity generated than you can use. But there will also be times when you’re short, during the summer, in the day. The way you get around the shortage is by having backup, and that means generally gas. That increases the cost because you have to pay the capital cost of equipment that is staying idle for a significant fraction of the year. When you have excess, you can produce cheap hydrogen. There are lots of things you can do with it. The first and most obvious is make nitrogen fertilizer. There are other creative things you could imagine doing with it. If you have hydrogen and CO2, you could make methanol and make fuel to run in automobiles. If we had a better grid—which should be a serious emphasis—if I was short of electricity in Texas I could buy it from wherever they don’t need it. The chances are pretty high that when the wind isn’t blowing in Texas, it’s blowing in Massachusetts or somewhere else. E@H: Are there particular research priorities that should be set to advance either the science or the policy of climate change? Jim Anderson: What’s really crucial are the feedbacks within the climate structure that control the way heat, thermal energy, is flowing into the major climate reservoirs, the arctic ice cap, and the glacial systems. We don’t know how rapidly heat is flowing into the ocean because we don’t have the observing systems. We don’t know how rapidly the climate structure—determined by temperature, water vapor, and cloud systems—is changing, because we don’t have the observations. We don’t know how the ocean currents are changing in response to recent increases in carbon dioxide because we don’t have the observations. We don’t know how fast Greenland is losing its glacial structure because we don’t have observations there, either. We don’t know how fast carbon is coming out of melt zones in both the Siberian and Alaskan tundra, nor the oceans, because we don’t have the observations. So here we are, with an extremely time-de- Peter Huybers, assistant professor of earth and planetary sciences. pendent problem that is predictable only if we have these basic pieces of information on how the system is responding— and we don’t have any of the required observations. These aren’t expensive observations… we’re not talking about even a minor blip on the economic structure. Steve Wofsy: [In March] there was a National Academy of Sciences report out on measuring and understanding the sources of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. This report basically asks the question, “If we have a treaty to restrain emissions of greenhouse gases, how well can it be verified?” If you read the material coming out of Copenhagen, you realize that monitoring and verification were at the center of the debate between Obama and the prime minister of China. The NAS panel laid down several parallel approaches. One is to improve self-reporting mechanisms. Another parallel track is to try to make measurements—either in the atmosphere or proxy measurement of economic activities—that you can use to validate these inventories. The question Harvard University Center for the Environment 7 “Climate change is the kind of thing that at any one point in time, never looks like the most important thing. Healthcare or wars or deficits… there’s always a more pressing issue. I think 50 years from now when we look back we’ll say, “Oh my! What did we do to this planet?” then arises, how well can you do that, and how do you do it? I speak mostly to the atmospheric measurements. You have three tiers: satellite data that gives you a global picture, very blurry, that sets the framework for everything else. Then you have ground stations and limited aircraft measurements in which you can do a better job estimating what’s coming from a region or a country. The third tier is to actually go hunting where the ducks are. If I identify the largest sources in a country, where are they? How many sources do I have to measure if I want to get, say, 70 percent of the sources? It turns out it’s not that many, perhaps 300. So one of the questions we’re asking right around Harvard is: Suppose I make atmospheric measurements in a big urban area, how accurately can I detect a trend, a change? If someone says we’ve cut our greenhouse gas emissions by five percent, can I check? We have a sensor on top of one of the buildings in Boston and another in Harvard Forest and I am putting one up in Worcester. This is all to ask the question: If you make measurements hour-by-hour, year in and year out at these places, can you detect changes in emissions? Emissions have a very strong fingerprint that they leave, but there’s a lot of variability in the atmosphere. So it’s a research question: How accurately can you detect a change? That hasn’t been looked at very much. The hope is within a year’s time we’ll have results that can help in negotiations, that people can really believe in and that can be demonstrated. E@H: When you think about your children and grandchildren, what kind of world do you think they’ll live in? Steven Wofsy, Rotch professor of atmospheric and environmental sciences. 8 Spring/Summer 2010 Michael B. McElroy, Butler professor of environmental studies. Mike McElroy: My grandchildren will live in a world with nine and a half billion people. The increasing disparity between the haves and have-nots, between rich and poor, even within countries, is going to be a challenge. I also think they’ll live in a world where the winners and losers will be different from what they have been historically. If I were to guess at what future climate is likely to be, I would say that Canada and Russia are likely to be major beneficiaries, and I would say the countries in the tropics, the poorer countries, are likely to be the major losers. Countries at mid-latitudes, like the United States and China, will be winners and losers. But the idea that we have warmer winters, open seas, longer growing seasons at high latitudes, the obvious places to benefit from that would be the big countries at high latitudes. You also have to worry here—and it’s not trivial—about the possibility of a catastrophic collapse of some of the major land-based ice sheets. You can sit back and say maybe that’s 100 years away. But the fact is we’ve been significantly and frequently surprised by how rapidly things are happening, and it is clear we don’t understand very well the stability of large ice sheets. The collapse of the [Larsen] Ice Shelf in Antarctica was not anticipated. And the best one can tell in retrospect is it was not caused by surface warming, it was actually caused by some relatively deep ocean water that was warmer than it used to be coming into contact underneath. That was enough to trigger a collapse of the sea-based ice. In turn, what does that do to the pinning of the land-based ice? That is a problem that serious people are seriously concerned about. Jeff Frankel: While I definitely believe that we ought to take action, I don’t experience the same emotional reaction that many others feel, to be honest. In part, this is because I think that whenever we try to imagine the Earth as our children and grandchildren will experience it, we always imagine wrong—and wrong in ways that are impossible to anticipate. It is also because, if we have a general continuation of the peace and prosperity of the last half-century, even in a worst case climate scenario, which would be pretty bad, I think my son and his children would still probably be better off than if they had lived in the first half of the 20th century (World Wars, depression) or in earlier periods of history. I hesitate to say that, because I don’t want to understate the problem we face, but it does offer a little perspective. Dan Schrag: I think it’ll be different in many ways that are hard to predict. One of the challenges of climate change is that thus far, it’s happening slowly enough that we get used to it. So my kids are growing up in New England used to warmer winters, used to being able to plant roses the first weekend in April. If you were here 50 years ago, that wouldn’t be the case. Mostly, I think many people, especially the more privileged among us, will bungle through it. And I hope my children will work hard to make the world as good a place as it can be. But we’re passing on a stacked deck to them. I think climate change is the kind of thing that at any one point in time, never looks like the most important thing. Healthcare or wars or deficits or who’s the next Supreme Court justice—there’s always a more pressing issue. I think 50 years from now when we look back—I’m hopeful I’ll live that long—we’ll say, “Oh my! What did we do to this planet?” I understand this as a geologist. We’re returning the planet to a state it hasn’t been in for tens of millions of years. And every living thing on Earth will be affected. F acult y P rofile Colleen M. Hansel D ownriver from many former coal and metal mines, water runs yolk yellow, lava red and electric green—a stew of heavy metals called acid mine drainage (AMD). Toxic, unsightly, and expensive to clean up, AMD puts vegetation, wildlife, and entire ecosystems at risk. Colleen M. Hansel, assistant professor of environmental microbiology at the School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, hopes to create a cost-effective way to bring these ravaged regions back to life. Current clean-up methods, Hansel says, involve costly and labor-intensive efforts such as digging limestone-filled pits to neutralize the water’s acidic pH. But the remediators she has in mind are plentiful, highly effective, and work for free. They are microorganisms that metabolize and detoxify iron, arsenic, and chromium, as well as fungi that remove toxic levels of manganese by making reactive minerals. The trick is figuring out exactly how the microorganisms perform these feats and then stimulating or seeding optimal microbial populations in polluted habitats. “Minerals are nature’s reagents for cleaning up contaminated surface and groundwater,” says Hansel. “What we try to do is figure out how to use microbes to make the needed minerals—or dissolve them— depending on the nature of the remediation needed.” Hansel became captivated by the idea that you could use organisms to clean up groundwater in the late 1990s, while studying soil chemistry and mineralogy at the University of Idaho; researchers had just discovered that common soil bacteria such as Shewanella oneidensis could survive miles underground without oxygen or sunlight. “The whole idea that there were little critters living in the soil that breathe metals like we breathe oxygen” she recalls, “ sounded like science fiction.” Later, while at Harvard, Hansel and collaborators at Penn State and at a nonprofit group intent on saving Appalachian rivers were surprised to discover that some fungi— multi-cellular microorganisms sporting long root-like tendrils—appear to be even better than bacteria at removing metals from water. Fungi come in more than 1.5 million species and are found virtually everywhere, so it is perhaps surprising when Hansel says that “We know essentially nothing about metal-transforming fungi.” Researchers have an even longer way to go to figure out how these organisms work so that they can be used to clean up toxins in the environment. “But considering the magnitude of the problem worldwide,” Hansel says, “it would be great if we could make a magic potion out of a mixed microbial community that we could then introduce into these systems to clean them up.” —Deborah Halber Harvard University Center for the Environment 9