ITALY 2010

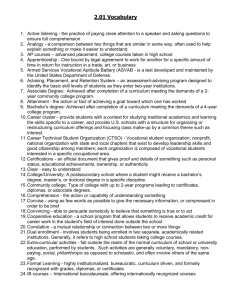

advertisement