The Influence of Forest Structure on Fire Behavior

advertisement

The Influenceof ForestStructureon Fire Behavior

JamesK. Agee

Collegeof ForestResources,University of Washington,Seattle,Washington

Westernforestshaveburnedfor millennia with a wide rangeof frequencies,intensities.

andextents.Someforestshaveflre-resistant

ffeesand othersdo not. The combinationof

the physicalcharactersof the fires themselves,togetherwith the adaptationsof the tree

speciesto fire, haveresultedin foresttypesthat can be classifiedinto naturalflre regimes

(Agee 1993). Three broadcategoriesof fire severitymay be defined,basedon the

physicalcharactersof fue and the lue adaptationsof vegetation:low, mixed or moderate,

and high. A low severityfue regimeis one wherethe effect of the typical historicalflre is

benign. Firesare frequent(often <20 years),of low intensiry,and the ecosystemshave

dominantvegetationwell-adaptedto survivefire. At the other end of the spectrurnis the

high severityfue regime,wherefires are usuallyinfrequent(often >100 years)but may be

of high intensity;most of the vegetationis at leasttop-killed. In the middle is the mixed or

moclerateseverityfire regime,wherefires are of intermediatefrequency(25-100years),

rangefrom low to high intensity,and havevegetationwith a wide rangeof adaptations.

Fire behavioris a function of fuels, weather,and topography,the "fire behaviortriangle".

All threelegsof the trianglehavesignificanteffectson fire behavior,but the fuels leg is

most relatedto forest structure,and is the only controllablefactor of the three. There are

also interactionsbetweenthesefactorswhich will be discussedlater. Foreststructure

consistsof flammablebiomass,whetherit is live or dead. Forestsfructurecan be

interpretedas three-dimensional

patchesof fuel, with differing amounts,sizeclasses,

arrangements,

and flammability. Somefuels, suchas large tree boles,riuely are consumed

by fire, while others,suchas surfaceneedlelitter, are partially to wholly consumedin

every fire. Others,suchas leavesin the treecrowns,are inconsequentialin surfacefires

but a major sourceof energyin crown fires. Foreststructureaffectsfire behavior.and fire

behaviorin turn affectsforeststructure.

It is importantto separatefireline intensityfrorn fire severity. Intensityis the energy

releaserate per unit lengthof fireline, and is a physicalparameterthat can be relatedto

flame length. It can be determinedfrom the productof biomassconsumption(energy)and

rate of spreadof the fire. Fire severityis an ecologicalparameterthat measures.albeit

somewhatloosely,the effectsof the fire. Two fires of the samefireline intensitycan have

quite differenteffectsbetweenan old-growthrnixed-coniferforest and a young plantation

of similar speciesbecausethe smallerplantationrees will be more easily scorchedand

havethinnerbark. The fire in the old-growthmay be of low severitywhile the plantation

fire is of high severity. We generallyare more interestedin fire severity,but must

approachseveriryfirst by estimatingfireline intensityand then using modelssuchas

FOFEM (Keaneet al. 1995)to predict treemortality from fireline intensity.

We havetraditionallyevaluatedfire and forest stmctureat the standlevel, and are

beginningto utilize landscape-level

tools to study larger-scaleissues.At the standlevel,

Page52

17th Forcst Vegetathn Managcment Conl'erencc

thereare horizontaland vertical componentsto the fuel matrix, and at the landscapelevel,

myriad patchesof foresteachwith a uniquefuel sffucturethat may carry fire along the

surfaceor throughthe ffee crowns. The following discussionis organizedaroundsurface

and crown fire behaviorratherthan all of the combinationsof fuel structuresthat could be

irnagined. The intent is to summarizesomeof the structuralcharacteristicsof foreststhat

fire behavior,or "fire-safe"forests. "Fire-safe"forestsare not

leadto rnanageable

fireproof,but will have:

.

.

.

Surfacefuel conditionsthat limit surfacefireline intensity;

Foreststandsthat arecornprisedof fire-toleranttrees,desoribedin termsof spccies.

sizes,and structures.

A low probabilitythatcrown fires will eitherinitiateor spreadthroughtheforest;

'fhese

characters

of one another.but it is possibleto definea rlatrix

arenot independent

conclitions

at the standlevel that constitutea fire-safeforest. One irnportarrt

of acceptable

here:not everyparcelof landscape

can or neeclbe treatedto

caveatrnustbe ernphasized

rnakeit "fire-safe".Therearecompetingobjectivesai.isociated

with biodiversityandfish

habitat

landscape

patches

prioritized

wildlife

that

suggest

units

or

be

for treatment,as

and

forestsalwaysburnedwith crown

not all can or shouldbe treated.Somehigh-elevation

probably

so

fire and

to makesuchforests"fire-safe"are

alwayswill, that attenrpts

objectiveswill sor.netimes

favor maintaininglatesomewhatfutile. Management

or old-growthforests,and while thosepatchesr-naynot be treatecl,

successional

forestpatchesrnaywell needfuelstreatmentto help protectthe latesurrounding

patchcs.

successionul

MANA(; IN(; SURI,'ACIt l'UltLS T( ) LI MIT I,'IRIILINFI IN'I'IINSI't'Y

oanlimit firelineintensityand lower potentialfire severity.It

Surfacefuel management

firelineintensityor increasefire severity,dependingon which fuelsare

canalsoincrease

rnanaged

and how the operationis conducted.Forestentryfor fuelsmanagement

pulposesusuallyresultsin alterednricroclimates,

andalthoughlesstotal bionrassrnaybe

present,moreof it rnay be in the deadfuel categoryand left lying on the forestfloor. The

of surfacefuelsso thatpotentialfirelineintensityremainsbelow somecritical

managenlent

(discussed

later)can be accomplished

throughseveralstrategies

level

andtechniques.

Arnongthe cornmonstrategies

arefuel removalby thinningtrees.adjustingfuel

produce

less

flammable

to

a

fuelbed,and "introducing"live understory

arrangernent

vegetationto raiseaveragemoisturecontentof surfacefuels.

interactwith one anotherto influencefirelineintensity.

The varioussurfacefuel categories

Althoughmorelitter andfine branchfuel on the forestfloor usuallyresultin higher

intensities,

that is not alwaysthe case. If additionalfuelsarepackedti-ehtly(low fuelbed

porosity),they may resultin lower intensities.Largerfuels(>3 inches)are ignoredin fire

spreadmodelsas theydo not usualll'affectthe spreadof the fire (unlessdecornposecl

lTth Forest Vcgetation Management Conl'erence

Page53

over longer

[Rothermel1991]).They may, however,resultin higherenergyreleases

periodsof time and havesignificanteffectson fire severity.

The effectof herband shrubfuelson firelineintensityis not simplypredicted.Firstof all,

moreherband shrubfuelsusuallyimply moreopenconditions,which areassociated

with

lowerrelativehurniditiesandhigherwindspeeds.Deadfuelsrnaybe drier,and therateof

spreadrnay be higher,becauseof the alteredmicroclirnatefror-nnroreclosedcanopyforest

with lessunderstory.Secondly,shrubfuelsvary significantlyin heatcontent.Waxy or

oily shrubslike snowbrtsh(Ceanothusvelutinus)or bearclover (Chamoehotia

foliolosa)

burn quite hot; othershavelower heatcontents.Perhapsmost important.though.is the

effectof the live fuelson moisturecontentof the fuelbed. FinedeadI'uelswill oftenbe at

moisturecontentsof l0o/oor less,while foliar moistureof live understoryvegetationwill

in the wetterthannormalsunrmerof

or higher. In the dry easternCascades

be at 100o/o

was 125(k,,

1995,averageshrubmoisturecontentin Septernber

and grasseswereat 93%

(J.K.Agee,unpublished

data).Thesefuelswill havea darnpening

effecton fire hchavior.

is annual,orperennialgrasses

andfbrbscure,thefine

However,if thegrasscornponent

cleadfuelcan increasefirelineintensity.Post-fireanalysesof fire rlanrageto plantr.rtitrrr

NationalForest

treesatierthe 19f17fires in the FlayfbrkDistrictof the Shasta-Trinity

(Weatherspoon

betweengrasscoverarrcl

andSkinner1995)showeda positiverelationship

clamage

and a negativerelationshipbetweenforb coveranddarnage(Figurel) , rnost

likely becausegrasseswerecureclandforbswerenot.

Management

of foreststructure

to reducefuelscanbe donemanually.rnechanically,

or

operatio115.

ollepotentialrernovultechlriquc

throughprescribed

burning.In harr,resting

is

Percent of

Plantations

with

Moderateto

Extreme

Damage

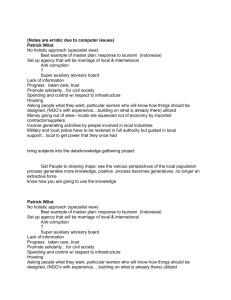

Figurel. Fire damageto mixedconif'erplantationin the l9tJ7fires was worsewhengrass

coverwas higherbut lesswhenforb coverwas higher(Weatherspoorr

anrlSkinner1995).

Moderateto extremedarnageincludesmore than 10%of treeswith >50a/(scorchtcr

=

>50o/o

Coverclasses

are0 = not presenUI = I -2()(/o:2

treeswith crownsconsumeci.

2 1 - 5 V nu

: n d3 = 5 l - l ( X ) 7 o .

Page 54

lTth Forest Veget:rtion Manauement Confercncc

whole-treeyarding, with trees cut by feller-bunchershauled to landings with grapple

skidders, and delimbing occurring at landings. Debris is chipped or burned there. Other

fuel removal strategiesmay include manual tree cutting and pile burning with sites

scatteredthrough the woods, or prescribedburning under moist conditions. These

strategieswill generally result in less fuel and more moderate fire behavior after treatment.

Adjusting fuel errangementmay be another strategyto produce a less flarnnrablefuelbed.

ln thinning operationswith harvesterforwarderequiprnent,limbing is clonein the woo<ls

directly aheadof the forwarder,which then rolls over the lirnbs.reducingsoil conrpuetiorr

effects of the equipment and rnaking a rnore cornpacttuelbed. A third strategyis often the

resultof thinning operations:recruitnrcntof understoryvegetation,both shrubsanclherbs,

that rnaintainhigh moisturecontcntanclprovide l clarnpening

eff'ecton fire belravi,rr.

Such treatmentwill not always reduce potential fire behavior or fire severity. lf the

thinning is a selectiveor crown thinning that rernoveslarger trees,the averagefire

resistance

of the standwilldecreasebecausethe residualshave a sr-naller

uverageclianreter

(Jonversely.

height,

potential

fire

sevcrity

wrll

and

and

be highcr.

a low thinningrvill

rcclucepotentialfire scverityas lr\ienrgcresiclualtrce siz-ewill increasr-.PotentialI'ire

is likely to changeafter treatrnent(Trrtrlcl, Figure 2). An unthinltedstantlof

['rehavior

pine with fire behaviorchunrctcristrcs

potrderosa

of NFFI- Morlel 9 ([3urgarrlutrl

R o t h e n n e l1 9 t 1 4 ) w i l lh a v e f l a n t e l e n g t h s o f- l - - 5 t ' e e t u n t l e r n r o d e r a t e f i r e w e a l hAesr 't.a r r r l

entry for thinningcoulclincreasepotentialf ire behaviorby addingfuel loaclingancllircl

depth. The thinning treatmenfif fuels wcre rerroved (suchas rvholetree yarding)coulcl

reducefire behavior to Model 9 values,or c:oulclincreasefuel loading r:ven trevonrl1hc

exampleshown (a lop and scatter approach,for exarnple). If thc stanclis thinnetlhc:rvilv

enoughto allow herb and shrub understoryto establish,and thc hcrtrsare not curerl. this

atlditionof Iive fuels,even with the increasedclc:acl

fuel loacling.recluccsfire ht'havitrr'

['rclowthat of Model 9. Generally.shrubfoliar ntoisturewill relnainhigh and herlr

moisturewill declineover the surnrner,particularlyif the herbsare annuals.

Prescribed

burninghasbeertfoundto recluce

subsequent

wildfiredarnagcfhroughits

effectson suffacefuel loadingreductionand on rnortalityof understorytreesand shrubs

thatmightcarryfire into thecanopytrees(Hehns1979,Buukley1992).In n.roslof our

westernUnitedStatesforests,prescribecl

fire hasnot beenappliedwirlcly enou-{hto have

rnucheffecton wilclfirebehaviorat a landscane

scale.

MANA( ;IN(i CROWN F'tIF]I,S'I'0 PRI.]VI.]N'I'

C ROWN !'I R F]}tT.]H

A V I() R

T'hedevelopment

andmaintenarlce

of a forestrelativelyfreeof L:rownfire potcntialis

primarilydeperrdent

on managernent

of the structure

of crownfuels. Topography,

and

weather,

theother"legs"of the "fire behaviortriangle",areeitherfixeclor uncontrollahle.

The regulationof crown fire potentialcan be apprroached

frorn two cornplernrntarv

perspectives:

. Prevention

of conditions

that initiarccn;wnf ire

. Pteventionof conditionsthal rlli'rr.l,

spleaclof crown f ire

lTth Forest Vegctation Management ('ont'crcnce

l'agc 55

If eitheror both of thesecriteriacan be achievedwithin a stand,thenthe chanceof crown

tire, and/orblowup fire behavior,is very low. lf they can be achievedacrossthe entire

landscape,

thepossibilitiesof blowupsareessentially

eliminated.ln the following analysis,

theseconditionsaredescribedat the scaleof the stand,and thresholdconditionsare

definedand appliedto real forests.

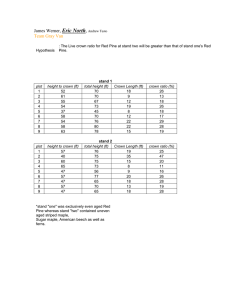

Table l" Simulatedfuel changesrrfterthinningwith moderateslashdisposalancl

greenupthroughdeveloprnent

subsequent

of a shrub/herbunrlerstory.Valuesfor the

only andnot basedon realclata.

thinnedandgreenupconditionsarefor demonstration

(ireenup

Fuel Pararneter*

NFFL Model 9

ThinnedStanil

1-hr load

I0-hr load

100-hrload

Live herb load

Live woody load

Fuel depth

2.92

0.41

0.15

4.( X)

3.( X)

3.( X)

4.(X)

3.00

)

3.(X

0.(x)

0.(x)

0.(x)

0.(x)

l.(x)

2.(X)

0 . 2)(

0.-50

0.5()

* load in tons/acre,depth in f'eel

6

5

Modelg

*'ffi-Thin

--#Greenup

4

Flame

Length3

(FT)

2

1

0

10

46

Windspeed(MPH)

Figure2. Effectof changingfuel contlitions(seeTable l) on pote.ntial

fire trehavior'.

" with l-, l0-. and l(X)-hrfuel rnoistures

Environmental

conditionsare"r.noderate

at 6.7

ancl8% andlive fuel rnoisturcat l?tt(k.

Page 5(r

lTth Forest Vcgctation Managt:nrent ('onl'ercncc

ConditionsThat Initiate Crown Fire

A fire rnovingthrougha standof treesmay move as a surf'acefire, an independentcrown

fire, or as a specffumof intermediatetypesof fire. The initiation of crown fire behavioris

a function of surfacefireline intensityand critical parametersof the treecrown layer: its

heightabovegroundand moisturecontent(Van Wagner1977). The criticalsurface

intensitvneededto initiatecrowninsis:

lo = (-,76P12

( E q u a t i o nI )

where

lo = critical surfar:eintensity

C = empiricalconstant,derived as 0.010 (Van Wagner 1977)

z = crown base height

content)

h = heat of ignition (largely a function of crown r-noisture

can be calculatedfor a rilngerrt'crowrl

Theretore.valuesfor critical surfaceintensity,1,,,.

baseheightsand foliar moisturecontents(Table 2). Theserepresentminirnurnlevelso1'

f irelineintensitynecessaryto initiatecrr)wl'lfirc. [:quivalentflarne lengthsin Sl arrcl

'l'able3equivalents.Byranr's(195t)1

E n g l i s h u n i t s i u ' e p r e s e n t e d i n T ' a b lF

eo

3 r. t h e

relationbetweenf-lamelengthanc'lfireline intensitywas usedratherthan Thor"nas'(19(r3)

t'lrrrne

length model. Rotherrnel(1991) usesThornas'tnodel,which is basedctna2ll

p()werlaw. ratherthan Byrarn'sscluareroot model, in his technicalrep()rton predictinr

behavioraud size of crown fires. However,to dest:ribeinitiirtingcortditions.Bytanr's

ntoclellnay be more appropriate.anclis usedextensivelyfor estitnatingthe f-larnelengthof

spreadingsurfacefires (Albini l9'76.Rothermel19133).Levels of fireline intensityor flanre

length below thesecritical levelsrnay resultin fires that do not crown but are still of stand

replacementseverity. For the lirnited range of crown hase heights arrdfoliar rnoistures

shown in Tables 2 and 3, the critical levels of fireline intensity anclflame length appear

more sensitiveto heicht to crown basethan to foliar moisture.

If the structuraldimensions of a stand and inforrnation about late surnrnerfoliar nruisturc

are known. then critical levelsof fireline intensitythat will be associatedwith crown fire

for that stand can be calculated. Fireline intensity can be predicted fbr a rartgeof stand

fuel conditions,topographicconditions.and anticipatedweatherconditions.so it is

possibleto link on-the-groundconditionswith.the initiatingpotentiaIf-orcnlwn fires. The

potentialfor managementto avoid crown fire initiation involveskeeping | < lo. T'hiscan

be accomplishedby rnanagingsurfacefuels such that I is kept well below In (see previtrus

section),or by r-nanagingfor suffir.'ientcrown base heights sueh that Io is large (seeTaLrle

,)\

| 7th Forest Vcgetation Management Conl'erence

Pagtr 57

Table2. Critical levelsof fireline intensity(kW m- l ) associatedwith initiation of crown

fire activity in coniferousstands.

Height of Crown Basc (m)

Foliar Moisture

It

12

lfi

2t)

I6(X)

2461

4526

6968

t)731

1024

I l{t{I

2891

5 3 2r

t(l9l

| 1449

4t9

I l tt-s

2n8

3353

(r159

9482

13252

l(x)

419

l3s4

24nti

3tt30

7036

10833

15 1 4 0

120

606

t 7l 4

3l4tt

1841

t3904

13709

l9 l s9

Content ('/o)

2

70

30n

tt7I

tr0

362

9()

with criticallevelsof firelineirrtensity

fr'ornTable2.

Table3. Flarnelengthsassociated

equation.

usingByrarn's(19-59)

Foli:tr Moisturg

Hcightol'Crown Birsc

C o r r t c n(t% , )

lll()lors(noiroslliXrl)

l ( r( 5 3 ) 2 0 ( 6 6 )

2 (6)

4 (11)

10

l.l ('1)

l . t ' t ( 6 ) 2 .r ( r J ) 2 . 8( e )

ft0

t . 2( 4 \

1 . 9( 6 )

2.s(tt)

.r.0( 10) 4 . 0 ( l 3 ) 4 . 9 ( r 6 ) s . 7 ( l e )

90

1 . 3( 4 )

2 . 0( 1 )

2 . 1( L ) )

3 . 3( 1 0 ) 4 . 3( 1 4 ) 5 . 3( 1 7 ) ( r " l( 2 0 )

l(x)

1 . 3( 4 )

2.t (1)

2 . 8( e )

3 . 4( l r ) 4 . 6 ( 1 5 ) 5 . ( r ( l i t ) 6 . 5 ( 2 1 )

t20

l " 5( 5 )

2 . 1( 8 )

3 . 2( 1 0 ) 1 . 9( l . l ) 5 .I ( 1 7 ) 6 . 2Q l ' t 7. f ( 2 4 )

Page 5tl

6 (20)

8 (26)

1 2( 4 O )

1 . 1( 1 2 ) 4 . 6( r 5 ) s . l ( l 7 )

lTth Forcst Vcgetation M:rnagemcnt C'onl'crence

Conditions That Allow Crown Fire To Spread

The crown of a forest is similar to any otherporousfuel medium in its ability to carry fire

and the conditionsunderwhich fire will or will not spread.The net horizontalheatflux,

E, into the unburnedfuel aheadof the fire is describedby Van Wagner(1977):

E=Rdh

(Equation2)

where

E = net horizontalheatflux, kW m-2

R = rate of spread,tt'ts"c-1

d = bulk clensityof crown,kg m-3

h = heatof ignition.kJ kg-|

Crown fuelsaretypicallyconsidered

thosewhiehinteractin the crown fire process,

usuallyneedlesbut possiblyincludinglichens,fine branches,

etc. Crownfires will stopif

eitherR or d, the rateof spreador bulk densityof the crown,fall below somenrinirnunr

value.

lf surfacefirelineintensity(l) risesabovethecriticalsurfaceintensityneeclecl

to initiate

crownfire behavior(le), the crown will likely becomeinvolvedin combustion.However,

Van Wagner(1977, 1993)recognizesthreetypesof orownfire behaviorthat can be

describec'l

by criticallevelsof firelineintensity(l) andratesof spread(R): (1) a passivc

crown fire, in which I > Io, but R is not sutficientto maintainorownfire activity;(2) an

activecrown fire, whereI > [o and R is abovesomeminimum spreadrate;and (3) an

independent

of

crown fire, whereI > Io and R throughthe crown is largelyindependent

heatfrom the surfacefire intensityl. A "crown-fire-safe"

landscape

would have

suchthat,at most,a passivetype of crown fire would resultundersevere

characteristics

fire weather.

Criticalconditionscan be definedbelow which activeand independent

crowrlfire spreadis

To

fire

unlikely.

derivetheseconditions,visualizea crown

as a massof fuel passingby a

stationaryflaming front (Figure3). The massflow rate(S) is the productof rateof spread

(R) and crown bulk density(d), and the unitsof S are Kg rn-2 ,""-1, or rnassper unit

crosssectionareaof crown per unit time. It can be describedin the contextof Equation

2:

S=Rd=E/h

(Equation3)

The massflow ratehassomeminimumproduct,So, belowwhich crownfire spreadwill

not occur,and that is determinedby combinationsof therateof spread(R) andcrown

bulk density(d). Van Wagner(1971)empiricallyderiveda minimummassflow rateof So

= 0.05, which he favorablycomparedto other valuesin the literature. Therefore,even if

conditionsare favorablefor crown fire initiation,the potentialfor spreadof a crown fire

lTth Forcst Vegetation Management Conl'erence

Pagc59

B

Figure3. Critical conditionsfor massflow ratecan be visualizedby passinga forestalong

a "conveyorbelt" througha stationaryflaming front. A. Under severefire weatherand

high rateof spread,crown masspassesthroughtheflaming front rapidlyand achievesSo

> 0.05,andcrown fire occurs. B. Wherecrown bulk densityis lower underthe samerate

of spread,critical levelsof So cannotbe obtainedand the fue remainsa surfacefire.

Page60

lTth ForestVcgctationManagementConf'erencc

canbe lirnitedby So < 0.05. The problemis thusreducedto one wherecriticalconditions

for R (rateof spread)and d (crown bulk density)may be defined,below which crown fires

will not spread.Individualcrown torching,andcrown scorchof varyingdegrees,rnaystill

occur.

Defininga setof criticalconditionsof R andd thatrnaybe definedby rnanagernent

activitiesis difficult. For givenlevelsof d abovesomeminirnunl R couldpotentially

increasein the presence

of strongwindsand allow an independent

crown fire (sensuVan

WagnerlL)77)to move througha stand. For this exercise.to defineconditionssuchthat

crownfire spreadwould be unlikely(thatis, produotsof R andd suchthatSn <0.05),

arbitrarythresholds

of R wereestablished

so that criticallevelsof d could be clefined.

The upperthresholdfor R for this exercise(R t ) wasdefinedas the maximumR of the

firesstudiedby Rothermel(1991),theeveningR of the Sundance

fire (1967),1.-J5

m secr. The rniddlerange(R2) wasdefinedby the maximumR of significantwind-drivenfires

sturliedby Rothermel,excludingthe eveningrun of the Sundancefire (PatteeCanyorr

1977,Sundance

afternoon1967,Sandpoint19t35,

Lily Lake l9tt0, Mink Creekl9l(lJ.Red

Bench l9lJl{,BlackTiger l9tt9),or 0"67m sec-l. The low end of therange(Rj) rvas

clefinecl

by theaveragernaximurnR of therunsof thesesarne7 fires.or 0.40 ,r, ,*.-l .

'['hcse

plovidea reasonable

rangeof threshold

valuesfor rateof spreacl.ln borealfbrests,

o rf n s e c - l , w i t h c r o w n b u l k c l e n s i t i e s g e n e r a l l y a b o v e 0 . 2

. f o h n s o(r1r( Y ) 2 ) e s t i r n a t e c l0R. 3

kg rn3. At the 1994TyeeFirein Washington,

R wasestirnated

at 0.3tt9nr sec-l irrnrixed

conif'erforestat MuclCreek(R. Sampson,

Tyeefire report),0.503

In sec-l in rnixed

c o n i f e r f o r e s t a t O k l a h o r n a G u l c h ( L . W i l l i a r n s , T y e e f i r e r e pl o

t )n. a

. 3r 4

r sn.d- c - l i n

lorlgepolepine/subalpine

fir forest(8. Walker.'Iyeefire report,frorn tatrleof ROS giverr

ternperatlrre/relative

hurnidityand HainesIndex),all within the rangedefinedby

Rotherrnel.

Ciiventhisrangeof R, and So = 0.05,alterrtative

levelsof d in equati()lt

3 are

(for Rj). bclowrvhichcrownfirr:

calculated

as0.037(for R1),0.074(for R2), and0.12-5

spreadwould be very unlikely.

A questiortable

in thisanalysisis thutR will rernainconstant

assunrption

asd is clruwn

dowrtto the criticallevel. [n fact, if R doesdeclineas d is reduced,then in theorya higher

levelof d rnightbe sustained

in theforestwithoutadditional

risk of crownfire spread.

This assun-rption

will be furtherdiscussed

later.

S'I'AND S'I'RUC'I'TJRT'S

AND CROWN I.'IRI.]

'l'he

preceding

analysis

hasestablished

criticallevelsof firelineintensitl'(l) anclseveral

possiblelevelsof crownbulk density(d) belowwhichcrownfire initiationandspreadare

unlikely. From theselevels,andwith additionalinformationon fire weather,surfar:efirel

"crown-fire-saf-e"

characters,

and standcharacters,

conditionsfor tbreststand:irnaylrc

clefined.It shouldbe ernphasized

forestis neitherfireproofnor

that a "crown-fire-safe"

likely to escapefree of wildfire damageat the standlevel. It is a standwhich is unlikelyto

generate

or allc'rw

the spreadof crown fire. Wildfire darnagewill clearlybe lessthanin

stands,but will not necessarily

unmanage(l

be low or absent.Management

of surfacefuels

lTth Forcst Vegetation Managcment Conl'crence

Pagc 6 |

is a corollary activity that can consffainsurfacefire intensityand reducechancesof crown

fire activity and damageto the residualstand.

Crown bulk densities(d) were calculatedfor ponderosapine (Pinusponderosa),Douglasftr (Pseudotsuga

menziesii),and grand fir (Abiesgrandis) for severaldiameter/density

cornbinations.Crown fuel biomassand crown volume were usedto constructa

rnass/volume

ratio (e.g.,crown bulk density)for eachspecies,sizeclass,and density.

Crown fuel as definedfor this report includesall foliar biomassplus 50 percentof other I hour tirnelagfuels (0 - 0.62 crn) in the crown. Otherfine fuels suchas lichenswere

ignoredfor this exercise,but would be sritical for somespeciesin other foresttypes (such

as subalpineftr[Abies lasiocarpa]). The "other" fuels hereare twigs and fine branches.

Half of thefine branchcategorywasconsidered

smallenoughto contributesignificant

process,

energyduringthe crown combustion

interpretedfrom datain Anderson(1969).

Foliar biomassof dominantsby tree speciesand sizeclasswas calculatedfrorn dataof

Browrr( 1971t)and Gholz et al. (1979),usingaverages

wheredatawereavailablefor a

speciesin both sources.Finebranchfuel additionswereaddedusingBrown's(l97tl) ratio

of foliar biornassto l-hr timelagsizeclassfor eachof the threespecies.The proportion

(at the 50% level)of 1-hrtimelagfuelsto foliar biomassrangedfrom I 1-lo/ofor sn.rallto

pine,26-20Vo

for smallto largeDouglas-fir,

largeponderosa

and2l-17% for srnalltcr

largegrandfir. Crown lichenbiomasswas not considered

in this analysis,but woulcl

increasecrown flammability for thosespeciescontainingsignificantamounts:granclfir and

sLrbalpine

fir.

At high treedensities,aggregatingthe crown fuel by sirnplernultiplicationof treebiornass

tir.nes

densitycan resultin overestimating

biomass.The total biomassper siteswascapped

at 50 tonnesha-1(about2(\ tac-l;. tris is a high crown fuel loacl(seeRothermel1991)

andprobablyresultsin someoverestimation

of crown bulk density,but only at very high

rreedensitiesof largeffees. Thesecombinations

arewell beyondthepossiblecritical

levelsof d definedearlier,so arerelativelyunimportantin evaluatingcriticalbulk densities.

Crown volurnesweredeterminedfrom Brown (1978)for eachof the threespeciesby size

class. Live crown lengthwas usedas the criterionfor crown volume,so thatdead

for any of the threespecies.

branchesbelowthe live crown were not considered

(ienerally,the bulk densityof deadbranchesbelowthe treecrown will be too low to

generate

crownfire activity,althoughlower branchesmay helpto sustainflameactivityup

into the crownfrom surfacefuel combustion.

Crown bulk densitiesfor the threespeciesby sizeclassanddensityshowedsome

consistent

trends(Table4). Crown bulk densitiesweregenerallyIowestfor ponderosa

pine, intennediatefor Douglas-fir,and highestfor grandfir. For any given densityof

trees,orown bulk densityincreasedwith tree size,suggestingcrown fuel biomass

increased

morethancrown volumeas ffee sizeincreased.For any giventreesize,crown

bulk densityincreasedwith treedensity.

Pagt 62

lTth Forest Vegetation Management Conl'crcncc

Table 4. Crown bulk density(kg m3) by diameterclassand densityfor ponderosapine

(regulartype, first row of eachtriplet), Douglas-fir(bold type, middle row), and grandfir

(italics,third row).

AverageDiameter

(dbh- cm)

Tree Densitv Per Hectare

50

100

200

400

800

1600

3200

7n

+o vl

t6L

3L4

ffiY (L15 TP/,\,

.001

.002

.002

.002

.003

.003

.00s

.007

.009

.0ll

.014

.018

.022

.027

.036

.043

.055

.013

.088

. r1 0

1.62

7-,0

.003

.004

.006

.007

.007

.0 1 2

.014

.014

.024

.028

.028

.047

.055

.056

.094

.l I I

.ll3

.189

.223

.226

.378

t9.0-5

.005

.009

.008

.010

.0 1 7

.0 t6

.02r

.034

.033

.041

.068

.066

.083

.136

.t32

.t66

.272

.263

.333

.545

.409

.010

.012

.0 t3

.020

.025

.026

.041

.049

.0s2

.082

.099

.t 03

.164

.198

.206

.328

.353

.287

.397

.353

.287

.01I

.019

.023

.023

.039

.047

.047

.078

.095

.095

.155

.t90

.190

.310

.247

.292

.313

.247

.03r

.023

.023

.062

.048

.047

.124

.096

.095

.248

.l9l

.247

.361

)<)

.247

.033

.042

.066

.083

.r33

.194

.210

l-vrcf,er

t.2l

0,5

1,5

3t.75

r-) q

I

L.-/

44.45

[.5

63.5

)cn

1 0 1. 6 +

4A+

.005

.167

Missingdatain cells denoteseithercrown bulk densitieswith unrealisticsizeldensity

combinations

or cellsfor which datawerenot available.

The sritical bulk densityfor independentcrown fire spreadcan be evaluatedin terrnsof

Table4. For example,if the middle value of maximum crown fire rate^ofspread(R) were

chosenas a planningcriterion,thenthe criticald would be0.074kg mr. It would be

lTth Forcst Vegetation Management Conl'erence

P:rge63

reachedfirst by grandfir, and last by ponderosa

pine.for a comparablesetof treesizes

and densities.The differencesbetweenspeciesare not as greatas the differencesbetween

densitiesand sizeclassesfor thesethreespecies,suggesting

controlof standstructureis

r-nore

inrportantthanspecies.However,in termsof fire tolerancein the presenceof a

surfacefire, choiceof specieswill be critical,as somespecieswill developfire tolerance

rnuchfasterthanothers,and somemay neveradaptbecauseof thin bark. The datain

Table4 arefor purestandsof one species.Crown bulk densitiesof cornbinations

of

pine,show little difference

species,suchas a 50-50mix of Douglas-firandponderosa

frorn the purespeciestables,but rnakearrimportantassumption:

that therewill not be

crown stratification.Stratificationwill be very irnportantwhereone specieseannraintain

itselfin subordinate

Lrrownpositions,which will affectboth biornassandcrown volume,

andthereforecrown bulk density.Stratificationcan alsoaffectheightto crown base.

Again.it rnustbe stressed

thatthesetablesarespecificto single-sized,

non-stratif

ied

stands.

()I''I'HI], CROWN }IIII,K I)I.]NSI'I'Y'I'HRI'SHOI,I)

AN I.]MPTRICAI,'I'I.]S'I'

Lirnitecl

ernpiricalinforrnation

existsto evaluate

thepredictability

of thecrownbulk

clensitythreshold.Much of the existingdatais from borealforesttypes(Van Wagner

1977.19c.)3).

Crownfire activityin severalstandsburnedin the 1994Wenatchee

fires

wereevaluatcdwherechangesin crown fire activityoccurred.Dataon standdianreter

andclensityweregatheredby ForestServicepersonnelin severalstanclsSorneof the

standshadalsobeentreatedwith prescribed

burningor pile burningto linritcriticallevels

of firelincintensity(lo)frorn occurring,

but all rnayserueasernpiricaltestsof crownbulk

clensity

thresholds.

Crownbulk densities

werecalculated

from thestaudcharacteristics

information,

andrelatedto presence

or absence

of crownfire activity(Table5).

(Jnthinncdsturtdstencledto be crowrrstratified,and the useof thesetaLrles

lnay have

for thosestands.

biasedtheestirnates

sornewhat

The lgg4 firesappearecl

to havea bulk clensity

thresholcl

of il =0.10 kg rn3.with crown

fire activitylikelyabovethethreshold

andno orownfire activitybelowit. Typicallyin this

a r e a . u n t h i n u e d s t a n d s h a v e d > 0 . 1 0 w h i l e t sh li an rnxel sc d

l o n o It r. r e a c h c a s e w h e r e a

thinned-unthinnecl

waspossible,crown fires in adjacentunthinnt:cl

cornparist'rt

stands

droppedto the groundas surfacefires whenthey reachecl

the thinneclstanrls.In cvery

case,the unthirrned

werelessthan l()0yearokl standswith utixesof

anclthinnedstanrls

Douglas-fir

pine. The criticallevelof d ernpirically

andponderosa

clerivecl

herefits

(

d

=

0

.

0

7

4

\

a

n

d

R

2

(

d

=

0

. 1 2 5 )T. h e

h a l f w a y b e t w e e n t h e l e v ecl sl doef r i v e d f r o r n R l

apparentincreasein criticalle'velsof d aboveR 1 rnaysuggestthatmaximulnratesof R

d e c l i na

e s c r o w n b u l k c l e n s i t y d e c r e aI nstehse. 1 9 9 4 f i r e s , i t a p p e a r s t h a t d : 0 . 1 0 i s

aboutthe highestcrownbulk densitya stancl

canrnaintain

andavoidthepotcrrtial

fbr

crownfire behavior.

Pagc (rJ

VegctationManagcmcntConfercncc

lTth F-orest

Table 5. Relationof estimatedcrown bulk densityto crown fire behavior. Standsare

rankedin descendingorder of crown bulk density.

Location

Stand

:urd

Trentrnent

Vicinity Mallen Rinch

Aver:tge

Stand

Diameter

(cmlinl)

Average

Stand

Density

( t h : t - ll a c l l

Estirnated

Crown Bulk

Density, d

(kgrn3)

Comments

tln

Fire Behavior

MC-unthinned 11 I'/l

r700[689]

= 0.1-5

Crown fire activity

Vicinity MarshRcsidencoMC-unthinnod l7 l7l

l7{x)[689]

= ().1-5

Crown firo activity

Navirrc Coulcc

MC-unthinned ll l7l

l(x)()

[4(x)l = ( f .l 0

Crtlwn firo aclivity

V i c i n i t y M a l l e nR a r r c h

MC-thinncd

30 [ l2l

5(x)[2U)l

= ( ).()c.)

Crttwn l-iresltrps

N a v i r r eC o u l c c

MC-thinncd

30 ll2l

2s()tr00l

= 0.05

Crown lirc stops

Mud Crcck

Mc-thinned

30 ll2l

250I l00l

= 0.05

Crown fire slops

MirrshRcsidcncc

MC-thinncd

24 p.5l

225 1t111

= 0.035

Crown l'iro stops

At levelsof d nearthe threshold,fuel treatmentrnayhelp to redusethe chancesof crown

fire activity. Two of the caseexarnples(Table5) werenearthe threshold.Navarre

Coulee,a standwith no fuel treatmont,was at the crown bulk densitythresholdand

exhibitedcrown fire behavior.At the Vicinity MallenRanchsite,pruningandpile burning

of thinning/pruning

debrisreducedthe fuel laddereffectandlimited I ( Io, so that a

runningcrown fire droppedto the groundthereeventhoughd was relativelyhigh.

Clrownhulk densitycan be usedasa criterionto lirnit crownfire behavior.By nraintaining

(cl)of <0.10kg rn3,activeor inclependent

stancls

crownfire

at crownbulk clensities

activitycanbe linritecl.Sucha criterionhasboth advantages

andlirnitations.The

include( I ) that empiricalevidenceseemsto supporttheexistenceof sucha

advantages

threshold;(2) thatd can be calculatedfrom typicalstandexamdata,so thatcrown fire risk

can be evaluatedat the standlevel;and (3) thatsilviculturalprescriptions

can be designed

"crown-fire-safe"

protection

Ievel

include

at the stand

to

from crown fire, to make

forests.

Limitationsof usingthis criterionare (l) that fire may still burn throughstandsanddo

significantdarnagedependingon the sizeand speciesof trees,(2) althoughstandscanbe

made"crown-fire-safe",

we do not cuffentlyknow how much of the landscape

needbe

(3) that othercornpetingand

landscape;

treatedthis way to makea "crown-fire-safe"

irnportantobjectivesntay limit the scaleof suchtreatmentson the landscape;and (4)

higherelevationforestshavenaturallyburnedthis way for millennia,so that attenlptstn

lTth Forest Vegetation Managcment Conl'ercnce

Page65

limit crown fire activity may be ecologicallyandeconornicallycost-effectiveonly in the

lower elevationforests.

Severalconstraints

to this analysisexist. The effectof slopewas not considered,

stands

with non-stratifiedcrowns were assumed,and crown bulk densitieswere calculatedfrom

crudedata. More validationof dimensionsof standswherecrown fires havebeen

observedto drop to the groundis needed.

DISCUSSI0N

It is clearthat foreststructurecan be manipulatedto reducethe severityof fire events.

The challengeis to rneldfuel strategies

with otherforestmanagement

objectives,and

beingableto selectproperfuel treatmentsandprioritiesfor treatment.In general,forests

with low severityfire regimesshouldhavehighestpdority for treatrnent,

and thatpriority

shoulddeclinein the high severityfire regirnes.The low severityfire regirnes(suchas

nrixedconifer)haveundergone

the rnostchangesincefire exclusionpolicieswereenacted.

high

levelsof bothrisk (chanceof a fire starting)andhazard(fuelsandtheir

anclhave

condition.suchas low fuel moisture).In the low severityfire regimes,strategies

that

potential

both surfaceand crown fire

are more likely to be adoptedthan in the

acldress

rnoclerate

to high severityfire regirnes,whereif fuel treatments

areappliedthey will havea

lcsssignificanteffectdue to generallylowerrisk"

sense,

either"tnoderate"

lrru conceptual

treatments

canbe considered

or "intensive".

Moderatetreatrnent

objectivemay focuson

areasarethosewherethe fuel manaBement

re<luction

of potential surfacefire intensity,so that | < Io. Firesmovingthroughthese

tirrestswill havelesschanceof crowningpotential.Low thinning,pruning,anclsurface

fuel treatrnent

with pile or broadcast

burningrnightbe amongthe fuel reducticln

includesthe techniques

techniqucs

applied.Intensivemanagement

aboveplus

<0.10 kg rn3,so thatevenunderseverefireweather

l'nanagelnentof

crownbulk clensity

fire is still likely to occur,but

thc fire is likely to renraina surfacefire" In bothtreatments,

will be higher. Fire severityin areasburnedrnay

thechancesof effectivefire suppression

species,the wildfire effect

bc lower,but if thetreesaresmallor areof lessfire-resistant

ruraystill be severe.

priority is high,thereis still rnuchuncertaintyabouthow

Wherefuel rnanagement

shouldbe applied. Ratherthanattempta "one-size-fits-all"

treatments

approach,there

nraybe insteada combinationof approaches

thatcanbe appliedto eachsituation

dependinguponthe foresttype andcompetingobjectives(Figure4). The gradientof

rangesfrom no treatmentat all to intensivetreatmentover the

treatmenton a landscape

possible)areshownin Figure4 and

steps(otherszLre

entirearea. Someintermediate

include"interior"no treatmentareassunoundedby intensivetreatmentareas,or no

by areaswith moderateto intensivetreatment.

treatmentenclavessurrounded

Pagc 66

lTth Forest Vegetation Management Conl'crcncc

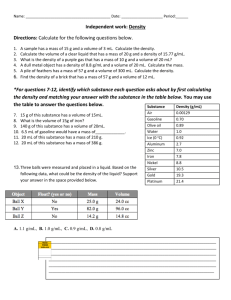

LandscapeFuel ManagementAlternatives

No Treatment

Treatment

ffi vooerate

Treatment

ffi tnt"nsive

Irigure.1. Landscape

level approaches

to fuel rnanagement

crossa gradientfiom no

trcatnlentto intensivetreatmentacrossthe entirelandscape.Intermediate

approaches

(upperright, lower left) combinesomeareaof no treatrnentwith otherareaswhere

moderateto intensivetreatmentsare applied. [n theseexample,rnoderatetreatments

adclress

reductionof surfacefire intensity;intensivetreatments

addressboth surfacefire

anclcrownfire intensitv.

questionremains:how rnuchof a landscape

l.he $64,(X)0

needbe treatedto makeit

relltively fire-safe'/The answerto this questiondoesnot dependon fuelsmanagement

can pay for themselves;

alone. Someof thesetreatments

otherswill not, so will dependon

how rnuchmoneyis available,and how it canbe disributed. Fueltreatrnent

requires

access,so that "no treatrnent"

areasrnayby defaultincludeareaswhereroadsare not in

placeas well ls ireas wherespecificforeststructures(suchas late-successional

forest)are

desired.However,evenif the answersto theseperipheralquestionsareavailable,we

question.exceptto say

reallydort'tknow how to completelyanswerthefuel management

"firesafe".

that as more of the landscapeis treated,it becomesmore

In the 1994

Wenatc:hee

fires, areasthat had beenthinnedand prescribedburnedover the last 20 years

had si-unificantly

reducedfire behavior,but the topsof the standswerescorchedfrom heat

produceclat otherplaceson the landscape

that had not beentreated.The treatedareas

wereat a scaleof severalhundredacres,andclearlywerenot largeenoughto be effective

at reclucingfire severity,as most of the scorchedtreesdied.

| 7th Forest \/egetation Management Conl'erence

Pdge 67

We havemadesomegeat stridesin understandingthe effectsof foreststructureon fire

behavior,but somemajor challengesremain. Thesechallengesare largely landscape-level

issues,similar to many otherof our currentforestmanagementchallenges.

LITERATURE CITED

Agee,J.K. 1993.Fire ecologyof PacificNorthwestforests.

IslandPress.Covelo.CA.

Albini, F. 1976. Estirnatingwildfire behaviorandeffects.USDA For. Serv.Gen.Tech.

R e p .I N T - 3 0 .

Anderson,H.E. 1969. Heat transferand fire spread.USDA For. Serv.Res.Pap.INTBrown.J"K. 1978.Weightanddensityof crownsof RockyMountainconifers.USDA

For. Serv.Res.Pap.INT-197.

Buckley.A.J. 1992. Fire behaviourandfuel reductionburning:Bemm River wildfire,

.

October,l9tl8. AustralianForestry55: 135-147

1984.BEHAVE: Firebehaviorpredictionandfuel

Burgart,R., andR.C.Rotherrnel.

rnocleling

system FUEL subsystem.USDA ForestServiceGen.Tech.Rep.INT161

Byranr.G.M. l9-59.Cornbustion

of forestfuels.[n: Brown,K.P.(ed) Forestfire:

Controland use. McGraw Hill. New York.

(lholz, H.A.,C.C.Grier,A.G. Carnpbell,

andA.T. Brown. 1979"Equations

for

estirlriltingbiomassand leaf areaof plantsin the PaoificNorthwest.ForestResearch

La[rRes.Pap.41. OregonStateUniversity.Corvallis,Oregon.39 pp.

Helrns,J.A. 1979. Positiveeffectsof prescribed

burningon wildfire intensities.Fire

Managemen

Nto t e s4 0 : l 0 - 1 3 .

.fohnson,E.A. I 992. Fire and vegetationdynamics:Studiesfrom the North American

forest. CambridgeUniversityhess. Cambridge,U.K. 129pp.

br,rreal

Keane.R., E.D. Reinhardt,and J.K. Brown. 1995. FOFEM: A first orderfire effects

rnodel.p.214 [n: Proceedings:

Symposium

on fire in wilderness

andpark

rnanagernent.

USDA For. Serv.Gen.Teoh.Rep.INT-GTR-320.

Rotherrnel,R. l9l't3. How to predictthe spreadandintensityof forestand rangefires.

TJSDAFor.Serv.Gen.Tech.Rep.INT-143.

R. 1991. Predictingbehaviorand sizeof crown fires in the northernRocky

Rotherrnel.

Mountains.USDA For. Serv.Gen.Tech.Rep.tNT-438.

Thomas,P.H. 1963. The sizeof flamesfrom naturalfires. In: Proceedings,

ninth

(international)

syrtrposium

on combustion 1962August27 Septenrber

I ; Ithaca,

NY. New York: AsadernicPress.:844-859.

Van Wagner,C.E. 1977. Conditionsfor the startand spreadof crown fire. Canadian

7: 23-34"

Journalof ForestResearch

V a n W a g n e r , C . E1. 9 9 3 .P r e d i c t i o n ocfr o w n f i r e b e h a v i o r i n t w o s t a n d s o f j a c k p i n e .

Journalof ForestResearch

Clanadian

23:442-449.

Weatherspoon,

C.P.,and C.N. Skinner.1995. An assessment

of factorsassociated

with

darnageto ffeecrownsfrom the 1987wildfiresin northernCalifornia.ForestScience

4l:-130-451.

Pagc 68

lTth Forest Vegetation Managcmcnt

Conl'erence