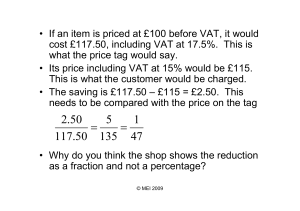

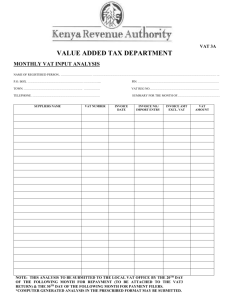

4 Value Added Tax and Excises

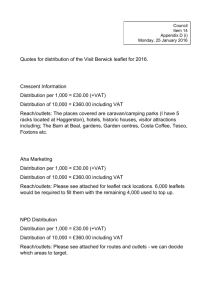

advertisement