Zero Net Land Degradation: A report prepared for the Secretariat

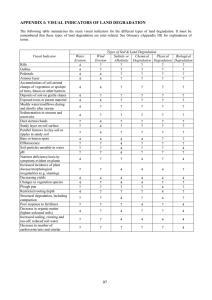

advertisement