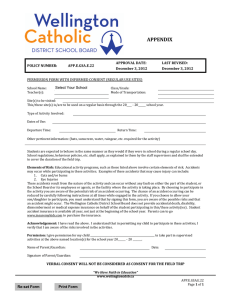

2008-46

advertisement