Document 12143300

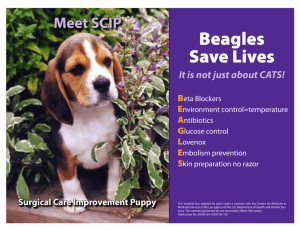

advertisement