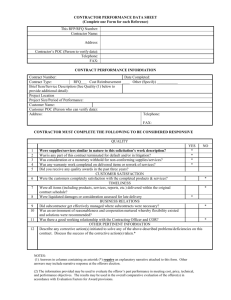

Construction Manager/General Contractor Issue Identification

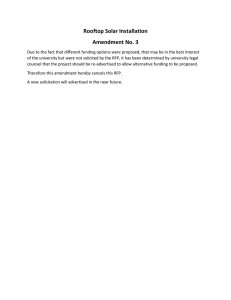

advertisement