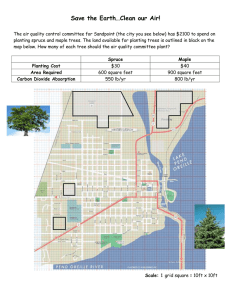

Road to a Thoughtful Street Tree Master Plan 2008-32 h...Knowledge...In

advertisement