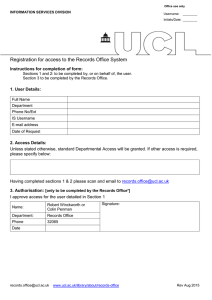

UCL Institute of Child Health 30 Guilford Street London

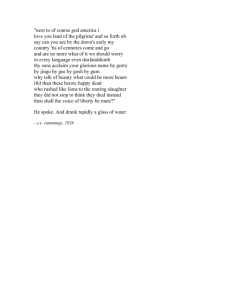

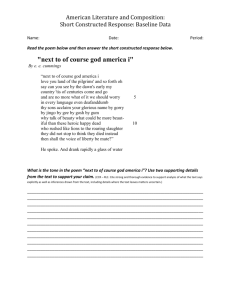

advertisement