Literature and Environment Further Lawrence Buell, Ursula K. Heise,

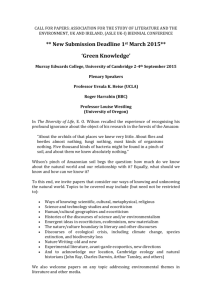

advertisement