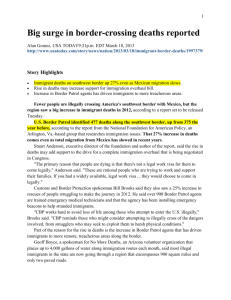

Humanita rian Crisis: Migrant Deaths at

advertisement