62 ZEF Bonn Food Security in

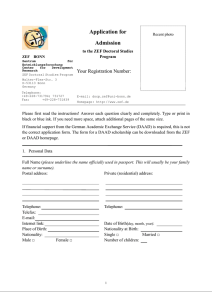

advertisement