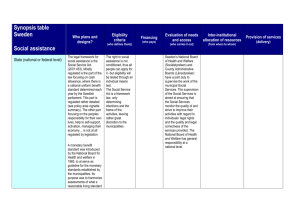

TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES .......................................................................................................... VI

advertisement