Deakin Research Online

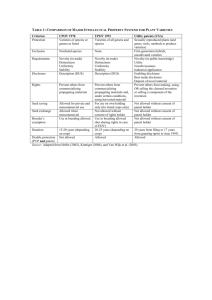

advertisement