Improving Diet in Low-Income Neighborhoods Leveraging the Food Environment for Change

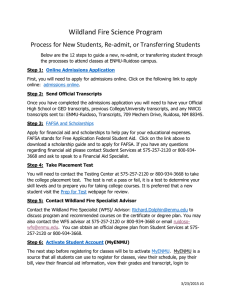

advertisement