Applying Market Mechanisms to Central Medical Stores

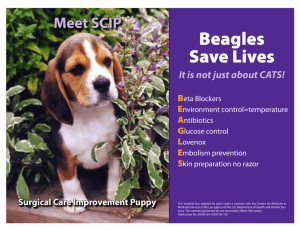

advertisement