I’m Sorry About the Rain! Superfluous Apologies Demonstrate Alison Wood Brooks

advertisement

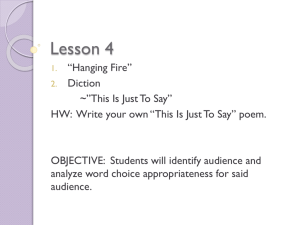

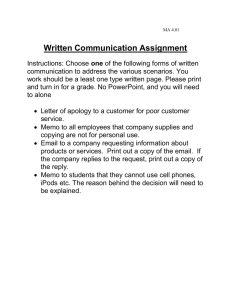

Article I’m Sorry About the Rain! Superfluous Apologies Demonstrate Empathic Concern and Increase Trust Social Psychological and Personality Science 00(0) 1-8 ª The Author(s) 2013 Reprints and permission: sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/1948550613506122 spps.sagepub.com Alison Wood Brooks1, Hengchen Dai2, and Maurice E. Schweitzer2 Abstract Existing apology research has conceptualized apologies as a device to rebuild relationships following a transgression. Individuals, however, often apologize for circumstances for which they are obviously not culpable (e.g., heavy traffic or bad weather). In this article, we define superfluous apologies as expressions of regret for an undesirable circumstance for which the apologizer is clearly not responsible. Across four studies, we find that superfluous apologies increase trust in the apologizer. This effect is mediated by empathic concern. Issuing a superfluous apology demonstrates empathic concern for the victim and increases the victim’s trust in the apologizer. Keywords superfluous apology, apology, trust, benevolence-based trust, empathy, stochastic trust game Hi, folks. Well, I’m sorry about the rain. President Bill Clinton (August 1995) Apology research has presumed that the apologizer bears responsibility for harming the victim. This presumption of responsibility is embedded in existing conceptualizations and definitions of apologies. According to Goffman (1971), an apology splits an individual into two parts, ‘‘one half of the individual representing the wrongdoing, and the other half . . . hoping to be forgiven’’ (p.113); and apologies have been defined as ‘‘admissions of blameworthiness and regret for an undesirable event that allow actors to try to obtain a pardon from audiences’’ (Goffman, 1971; Lazare, 2004; Ohbuchi, Kameda, & Agarie, 1989; Scher & Darley, 1997; Schlenker, 1980; Schlenker & Darby, 1981, p. 271; Schweitzer, Hershey, & Bradlow, 2006; Tavuchis, 1991). Incorporating this definition, the extant literature has studied apologies as a post hoc device for restoring relationships between a culpable apologizer and a target (Haselhuhn, Schweitzer, & Wood, 2010; Kim, Dirks, Cooper, & Ferrin, 2006; Kim, Ferrin, Cooper, & Dirk, 2004; Van Kleef, De Dreu, & Manstead, 2010). We argue that this approach is overly narrow. Many individuals, such as Bill Clinton, apologize when they are clearly not responsible. In contrast to the existing research that has assumed that the apologizer is blameworthy, we investigate the use of apologies for situations in which the apologizer is obviously not at fault. We redefine apologies as expressions of regret for an undesirable event or situation. This broader definition no longer constrains apologies to include ‘‘admissions of blameworthiness’’ and does not presume that an apology aims to obtain ‘‘pardon from audiences.’’ In particular, our broader definition includes what we term superfluous apologies: expressions of regret for an undesirable circumstance that is clearly outside of one’s control. Although prior work has assumed that apologies reflect admissions of blameworthiness for causing harm, superfluous apologies are common. For example, Japanese often apologize even when they are not blameworthy (Maddux, Kim, Okumura, & Brett, 2011). It is possible that people feel guilty when they observe others suffering from an undesirable circumstance, even when the observer is blameless. Prior work has demonstrated that culpability is not required to experience feelings of guilt (e.g., Baumeister, Stillwell, & Heatherton, 1994). Feelings of guilt in such contexts, separate from feelings of responsibility, may be sufficient to motivate an apology. By issuing a superfluous apology, the apologizer communicates that he has taken the victim’s perspective, acknowledges adversity, and expresses regret. For example, though Bill Clinton may have been dry and comfortable, by saying ‘‘I’m sorry about the rain,’’ he communicates that he understands the 1 Harvard Business School, Negotiation, Organizations & Markets Unit, Boston, MA, USA 2 Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania, PA, USA Corresponding Author: Alison Wood Brooks, Harvard Business School, Negotiation, Organizations & Markets Unit, Baker Library 463, Boston, MA 02459, USA. Email: awbrooks@hbs.edu 2 crowd’s perspective and expresses regret that they are wet and uncomfortable in the rain. Previous work demonstrates that negotiators who express regret or guilt are liked better than those who do not (Van Kleef, De Dreu, & Manstead, 2006). This finding is related to apology research that has found that the act of apologizing represents an empathic expression that ‘‘demonstrates the offenders’ recognition of and concern for their victims’ suffering’’ (Fehr & Gelfand, 2010, p. 38). We fundamentally advance prior apology work by demonstrating that superfluous apologies demonstrate empathy even in the absence of culpability. In our investigation, we expect superfluous apologies to demonstrate empathic concern and consequently increase benevolence-based trust, the extent to which we believe someone is kind and concerned about our well-being (Johnson, Cullen, Sakano, & Takenouchi, 1996; Mayer & Davis, 1995). Benevolence-based trust correlates strongly with liking and behavioral trust. Although we anticipate several perceptual and behavioral benefits of superfluous apologies, some prior work suggests that apologizing may have drawbacks (Bergsieker, Shelton, & Richeson, 2010). For example, Tannen (1996, 1999, 2001) conjectures that apologies may harm perceived power and competence, especially for women. Consequently, in addition to measuring empathy and benevolence-based trust, we also explore how superfluous apologies influence perceptions of power and competence-based trust, the perception that someone possesses the ability and skills required for a task (Butler & Cantrell, 1984; Kim et al., 2004). Study 1 In Study 1, we investigate the effect of superfluous apologies on trust. In this study, we measure behavioral trust using a novel version of the trust game, the stochastic trust game, and we collect attitudinal measures of trust and liking. Method Participants We recruited 178 students from a Northeastern university to participate in an experiment for pay (60.0% female, Mage ¼ 19.98, standard deviation [SD] ¼ 2.46). Participants received a US$10 show up fee and had the opportunity to earn additional compensation of up to US$9 based on the performance. Design and Procedure We randomly assigned participants to one of two conditions (superfluous apology vs. no apology). Our primary dependent variable was behavior in a repeated trust game. We recruited participants to a behavioral laboratory. We informed participants that they would be playing several rounds of a repeated trust game with an anonymous counterpart in the room (e.g., Berg, Dickhaut, & McCabe, 1995; Murphy, Social Psychological and Personality Science 00(0) Rapoport, & Parco, 2000). In reality, all participants played the same role against a common, computer-simulated counterpart. We informed participants that they would be endowed with US$6 in each round, which they could either pass to their counterpart or keep. If they chose to pass the US$6 to their counterpart, the money would be tripled (to US$18). The counterpart could then either keep the US$18 or pass half of the money (US$9) back. Consistent with prior work, we operationalized trust as participants’ decision to pass their endowment (Bohnet & Huck, 2004; Engle-Warnick & Slonim, 2004; Haselhuhn et al., 2010; Lount & Pettit, 2012; Malhotra & Murnighan, 2002). We explained to participants that both players would make decisions simultaneously and that players would learn about their counterpart’s decision regardless of what their counterpart chose. For example, if participants chose to keep their endowment, they would still learn whether or not their counterpart would have returned US$9. Importantly, we explained that there was a 25% chance that the computer would override the counterpart’s decision on each round, but the computer would never override the counterpart’s decision on the last round. We term this version of the game the stochastic trust game. We informed participants that, after each round, we would reveal both players’ decisions, whether the computer overrode their partner’s decision, and the outcome of the round. All participants completed four rounds of the trust game. Both the decision of their counterpart and the purportedly random overriding action of the computer were preprogrammed. In Rounds 1 and 2, participants learned that their counterpart chose to return US$9 and that the computer did not override this decision. In Round 3, participants learned that their counterpart chose to return US$9 and that the computer overrode this decision. After receiving feedback from Round 3 and before making their decision for Round 4, half of the participants received the following superfluous apology message from their counterpart: ‘‘I’m really sorry the computer changed my choice last round.’’ In the no apology condition, participants did not receive a message. Before Round 4, we announced that everyone would know that this was the last round. The decision to pass in the final round was our primary dependent variable. The decision to pass in the final round, after the endgame has been announced, represents the best measure of trust (cf. Bohnet & Huck, 2004; Engle-Warnick & Slonim, 2004; Haselhuhn et al., 2010; Malhotra & Murnighan, 2002; Schweitzer et al., 2006). After the trust game, participants rated their partner with respect to competence-based trust (3 items, a ¼ .91), benevolence-based trust (3 items, a ¼ .83), likeability (10 items, a ¼ .88), and perceived power (for measure details refer online supplemental material found at http://spps.sagepub.com/ supplemental). Results We found no main effects or interaction effects for gender, and we report all of our findings collapsed across the gender. Brooks et al. 3 85 77% Passing Rate (%) 80 75 65% 70 65 60 55 Superfluous Apology No Apology Experimental Condition Figure 1. Superfluous apology increases trusting behavior in a repeated trust game (Study 1). in the superfluous apology condition reported significantly higher benevolence-based trust in their counterpart (M ¼ 3.54, SD ¼ 0.68) than did participants in the no apology condition (M ¼ 3.02, SD ¼ 0.85), t(161) ¼ 4.35, p < .001. We did not find a significant effect of experimental condition on perceptions of competence-based trust (p ¼ .23). Perceptions of benevolence-based trust mediated the relationship between superfluous apology and trusting behavior (Baron & Kenny, 1986). By including benevolence-based trust in our model, the influence of receiving a superfluous apology was no longer significant (b ¼.09, p ¼ .35) but perceptions of benevolence-based trust predicted trusting behavior (b ¼ .40, p < .001). Because our dependent variable was binary, we ran a 5000-sample bootstrap (Preacher & Hayes, 2004, 2008) using MacKinnon and Dwyer’s (1993) logistic regression method and found a standardized indirect effect of.17 (SE ¼ 0.05, 95% biased-correct CI ¼ [0.08, 0.23]). We depict this mediation effect in Figure 2. Perceptions of benevolence-based trust .40*** .34*** Trusting behavior Superfluous apology .09 (.24*) * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001 Figure 2. Perceptions of benevolence-based trust mediate the relationship between superfluous apology and trusting behavior (Study 1). Values are standardized regression coefficients. The value in parentheses represents the total effect of superfluous apology condition on trusting behavior. Trusting Behavior Participants were more likely to pass US$6 to their counterpart in the last round when they received a superfluous apology than when they did not receive a superfluous apology: 77% (65 of 84) of participants in the apology condition passed US$6 compared to 65% (51 of 79) of participants in the no apology condition. We conducted a logistic regression with experimental condition as the independent variable, passing behavior in the first three rounds as a covariate to account for baseline trust,1 and final round passing behavior as the dependent variable. We found a significant effect of superfluous apology on trusting behavior, b ¼ .24, B ¼ 1.11, standard error (SE) ¼ .45, w2(1, N ¼ 163) ¼ 6.10, p ¼ .01. We depict this result in Figure 1. We also found that trusting behavior in the first three rounds significantly predicted passing rate in the last round, b ¼ .59, B ¼ 3.88, SE ¼ .64, w2(1, N ¼ 163) ¼ 37.33, p < .001. Perceived Trust Consistent with our prediction, receiving a superfluous apology increased perceptions of benevolence-based trust. Participants Likeability and Power Participants in the superfluous apology condition liked their counterpart significantly more (M ¼ 3.60, SD ¼ 0.47) than did participants in the no apology condition (M ¼ 3.28, SD ¼ 0.54), t(161) ¼ 4.15, p < .001. We did not find a significant effect of receiving a superfluous apology on the perceived power of the counterpart (p ¼ .89). Discussion In Study 1, participants who received a superfluous apology were more trusting than were participants who did not receive an apology. This is true for both our attitudinal measure of benevolence-based trust and our behavioral measure of passing decisions in the trust game. Perceptions of benevolence-based trust fully mediated the effects of superfluous apologies on trusting behavior and liking toward the counterpart. Study 2 In Study 2, we extend our investigation by considering alternative explanations. In Study 1, it is possible that our control condition decreased benevolence-based trust. In the control condition in Study 1, the confederate sent no message. This might have seemed impolite. To investigate this alternative explanation, we include two different comparison conditions in Study 2. We include a traditional apology (‘‘I’m sorry to interrupt.’’) and neutral greeting (‘‘How are you?’’). In addition, we extend our investigation by exploring superfluous apologies in a new domain. In Study 1, both the unfortunate circumstance (the random action of the computer) and the outcome (behavioral measure of trust) were related to the trust game. In Study 2, the apology (for a flight delay) is unrelated to our measure of trust (lending a cell phone). We expect that an apology for a flight delay will increase trust even when the subsequent interaction is unrelated to the flight. 4 Design and Procedure We randomly assigned participants to one of the three betweensubject conditions (superfluous apology vs. traditional apology vs. neutral greeting). In all three conditions, we asked participants to imagine that they were waiting for a flight to visit a friend whose father recently passed away when the airline announces that the flight has been delayed for 2 hours. We asked participants to imagine that after they sat down in an adjacent boarding area, a passenger from a different, nondelayed flight approached them (full scenario included in online supplemental material found at http://spps.sagepub.com/supplemental). Participants then watched a short video in which a confederate, playing the role of the other passenger, approaches and asks to borrow their cell phone. The confederate makes this request in one of the following three ways: ‘‘Hi. I am sorry your flight is delayed. Can I borrow your cell phone?’’ (superfluous apology), ‘‘Hi. I am sorry to interrupt. Can I borrow your cell phone?’’ (traditional apology), or ‘‘Hi. How are you? Can I borrow your cell phone?’’ (neutral greeting). Participants then rated the confederate on measures of benevolence-based (a ¼ .87) and competence-based trust (a ¼ .70). We use the decision to lend a stranger a cell phone as our measure of trust. Cell phones are moderately expensive, small, fragile, and often contain private information. Handing a cell phone to a stranger makes the individual vulnerable and represents an act of trust. Results We found no main effects or interaction effects of gender, and we report all of our findings collapsed across gender. Perceived Trust We conducted a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with perceptions of benevolence-based trust as the dependent variable and experimental condition (superfluous apology vs. traditional apology vs. neutral) as the independent variable. Supporting our thesis, we found differences across the three conditions, F(2, 174) ¼ 11.81, p < .0001, Z2p ¼ .12. Planned contrasts revealed that the confederate was rated higher in benevolence-based trust following the superfluous apology (M ¼ 4.28, SD ¼ 1.15) than following the neutral greeting (M ¼ 3.34, SD ¼ 1.13, t(174) ¼ 4.85, p < .0001). The confederate was also rated higher in benevolence-based trust following the superfluous apology than following the traditional apology (M ¼ 3.88, SD ¼ 0.87, t(174) ¼ 2.06, p < .05). Further, consistent with past research showing that apologies can 4.8 4.28 Benevolence-based Trust We recruited 177 U.S. residents (Mage ¼ 27.69 years, SD ¼ 9.44; 30% female) to complete a 3-min online survey in exchange for US$.30. A 4.4 3.88 4 3.34 3.6 3.2 2.8 Superfluous Apology Conventional Apology Neutral Experimental Condition B Benevolence-based Trust Method Participants Social Psychological and Personality Science 00(0) 5 4.59 4.6 3.91 4.2 4.03 3.8 3.4 3 Superfluous Apology Acknowledgment Neutral Experimental Condition Figure 3. Superfluous apology increases perceptions of benevolencebased trust (Studies 2 and 3). serve as an interpersonal lubricant (Lazare, 2004; Tavuchis, 1991), we found that perceptions of benevolence-based trust were significantly higher in the traditional apology condition than in the neutral greeting condition, t(174) ¼ 2.75, p < .01. We depict this pattern of results in Figure 3 (Panel A). We also found a significant effect of the experimental condition on perceptions of competence-based trust, F(2, 174) ¼ 4.16, p ¼ .02, Z2p ¼ .05. However, as in Study 1, we did not find evidence that issuing a superfluous apology diminished perceptions of competence-based trust. Instead, we found that, compared to the neutral greeting condition (M ¼ 4.63, SD ¼ 0.97), perceptions of competence-based trust were significantly higher in both the superfluous apology condition, M ¼ 5.05, SD ¼ 0.92, t(174) ¼ 2.42, p ¼ .02, and the traditional apology condition, M ¼ 5.09, SD ¼ 0.97, t(174) ¼ 2.59, p ¼ .01. The latter two conditions did not significantly differ from each other (p ¼ .22). Discussion Participants rated a confederate to be higher in benevolencebased trust when the confederate used a superfluous apology (‘‘I’m sorry your flight was delayed.’’) than when the confederate used a polite greeting (‘‘How are you?’’) or a traditional apology (‘‘I’m sorry to interrupt.’’). This finding extends our investigation to a different domain and a different operationalization of trust. Brooks et al. 5 Method Participants contrasts revealed that the seller who apologized for the rain engendered higher benevolence-based trust (M ¼ 4.59, SD ¼ 1.00) than did both the seller in the acknowledgment condition, M ¼ 3.91, SD ¼ 1.00, t(307) ¼ 5.13, p < .001, and the seller in the neutral condition, M ¼ 4.03, SD ¼ 0.86, t(307) ¼ 4.23, p < .001. We found no difference in benevolence-based trust between the acknowledgment and neutral conditions (p ¼ .39). We depict this pattern of results in Figure 3 (Panel B). As in Study 1, we did not find a significant effect of experimental condition on perceptions of competence-based trust, F(2, 307) ¼ .36, p ¼ .70, Z2p ¼ .002, and none of the three pairwise comparisons were significant. We recruited 310 U.S. residents (Mage ¼ 32.33 years, SD ¼ 12.14; 52% female) to complete an online survey in exchange for US$.40. Likeability Study 3 In Study 3, we investigate the psychological mechanism that links superfluous apologies with trust. We expect superfluous apologies to reflect empathic concern. By saying ‘‘I’m sorry,’’ the superfluous apologizer acknowledges an unfortunate circumstance, takes the victim’s perspective, and expresses empathy for the negative circumstance, even though it is outside of his or her control. Design and Procedure We randomly assigned participants to one of the three betweensubject conditions (superfluous apology vs. acknowledgment vs. neutral). In all three conditions, we asked participants to imagine that they were about to purchase a used iPod on Craigslist. On their way to meet the seller, we asked participants to imagine that they got caught in the rain (full scenario included online supplemental material found at http://spps. sagepub.com/supplemental). When they meet the seller, the seller greets them in one of the following three ways: ‘‘Hi there. Oh, I’m so sorry it’s raining.’’ (superfluous apology), ‘‘Hi there. Oh, it’s raining.’’ (acknowledgment), or ‘‘Hi there.’’ (neutral). After reading the scenario, participants rated the seller on measures of benevolence-based trust (a ¼ .86) and competence-based trust (a ¼ .72) as well as likeability (‘‘The seller is likeable’’). We also adapted 7 items from Davis (1983) to assess perceptions of empathic concern (a ¼ .88; see online supplemental material found at http://spps.sagepub.com/ supplemental for details). A factor analysis with a varimax rotation validated that our measures of benevolence-based trust, competence-based trust, and empathic concern loaded onto three factors (using eigenvalue ¼ 1). The three composite scores indicate that our measures effectively captured the intended constructs. Results We found no main effects or interaction effects for gender, and we report all of our findings collapsed across gender. Perceived Trust The superfluous apology increased perceptions of benevolencebased trust. We conducted a one-way ANOVA with perceptions of benevolence-based trust as the dependent variable and experimental condition (superfluous apology vs. acknowledgment vs. neutral) as the independent variable. Consistent with our prediction, there were significant differences among the three conditions, F(2, 307) ¼ 15.06, p < .001, Z2p ¼ .09. Planned The experimental conditions significantly influenced perceptions of likeability, F(2, 307) ¼ 8.61, p < .001, Z2p ¼ .05. Planned contrasts revealed that the pattern of likeability mirrored that of benevolence-based trust: Participants in the superfluous apology condition liked the seller significantly more (M ¼ 4.39, SD ¼ 1.23) than did participants in both the acknowledgment condition, M ¼ 3.76, SD ¼ 1.16, t(307) ¼ 3.97, p < .001, and the neutral condition, M ¼ 3.91, SD ¼ 1.04, t(307) ¼ 3.00, p ¼ .003. The extent to which the seller was perceived to be likeable did not differ in the latter two conditions (p ¼ .35). Empathic Concern Perceptions of empathic concern varied significantly across conditions, F(2, 307) ¼ 20.69, p < .001, Z2p ¼ .12. Consistent with our prediction, planned contrasts revealed that perceived empathic concern was higher in the superfluous apology condition (M ¼ 4.27, SD ¼ 0.88) than in both the acknowledgment condition, M ¼ 3.57, SD ¼ 0.94, t(307) ¼ 5.93, p < .001, and the neutral condition, M ¼ 3.66, SD ¼ 0.73, t(307) ¼ 5.10, p < .001. Perceptions of empathic concern did not differ in the latter two conditions (p ¼ .44). Mediation Empathic concern mediated the effect of superfluous apology on perceptions of benevolence-based trust. The acknowledgment condition and the neutral condition were not significantly different on any measures, so we collapsed across these two conditions in our mediation analyses. When we included empathy in our model, the effect of superfluous apology was no longer significant (from b ¼ .30, p < .001 to b ¼ .06, p ¼ .19) and the effect of empathy remained significant (b ¼ .70, p < .001). A 5000-sample bootstrap test estimated a standardized indirect effect of .24 (SE ¼ .038, 95% biased-corrected CI [0.16, 0.31]), indicating full mediation.2 We depict this mediation effect in Figure 4. 6 Social Psychological and Personality Science 00(0) Perceptions of empathic concern .34*** .70*** Superfluous apology .06 (.30***) Perceptions of benevolence-based trust * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001 Figure 4. Empathic concern mediates the relationship between superfluous apology and increased perceptions of benevolence-based trust (Study 3). Values are standardized regression coefficients. The value in parentheses represents the total effect of superfluous apology condition on perceptions of benevolence-based trust. Discussion In Study 3, we contrasted a superfluous apology with an acknowledgment of the adverse circumstance (in this case, rain). We found that individuals rated the seller who issued a superfluous apology higher in benevolence-based trust and likeability than the seller who acknowledged the bad weather but did not apologize for it and the seller who made no mention of the bad weather. Supporting our thesis, empathic concern fully mediated the effect of the superfluous apology on perceptions of benevolence-based trust. Study 4 In Studies 1–3, we found a consistent boost in trust following a superfluous apology in both lab- and Web-based settings. In Study 4, we extend our investigation to a field setting. We investigated the consequences of issuing a face-to-face superfluous apology followed by a request to borrow a stranger’s cell phone. Method A male confederate who was blind to our hypotheses approached 65 strangers (30 female, 35 male), one at a time, in a large Northeastern train station and requested to borrow their cell phone. We depict the experimental setup in Figure 5. We conducted this study over the course of 2 days in November 2010 when the forecast called for steady rain. The accumulated precipitation during each of the 1-hour sessions was equivalent (0.06 inches of rain)3; the American Meteorological Society characterizes this level of precipitation as ‘‘moderate rain.’’ The confederate alternated the script he used across the 65 individuals he approached. Half of the time the confederate delivered a superfluous apology script, ‘‘I’m so sorry about the rain! Can I borrow your cell phone?’’ Half of the time the confederate delivered a neutral script, ‘‘Can I borrow your cell phone?’’ We recorded the date, time, gender of the participant, and whether or not the participant handed their cell phone to the confederate. We used the decision to hand over a cell phone to the confederate as our behavioral measure of trust. Figure 5. The confederate requests to borrow a stranger’s cell phone in the train station (Study 4). Results and Discussion Of the 65 participants, 18 (28%) volunteered to give their cell phone to the confederate. We conducted a logistic regression with trusting behavior as the dependent variable and apology condition, gender, and day as independent variables. Supporting our thesis, 47% (15 of 32) of the participants in the superfluous apology condition entrusted their cell phone to the confederate, compared to 9% (3 of 33) of the participants in the neutral condition, b ¼ .66, B ¼ 2.83, SE ¼ 1.15, w2(1, N ¼ 65) ¼ 5.99, p ¼ .01. We did not find main effects of gender (p ¼ .65), day (p ¼ .52), or interaction effects between apology condition and day (p ¼ .46) on trusting behavior. We depict these results in Figure 6. Results from this field study reveal that a face-to-face superfluous apology increases trusting behavior. Strangers were more likely to hand their cell phone to a confederate when the confederate apologized for the rain than when he did not. General Discussion Extant research has conceptualized apologies as expressions of remorse by culpable individuals to repair relationships and restore lost trust. We challenge this paradigm. We broaden the conceptualization of apologies to include expressions of Brooks et al. Cell Phone Lending Rate (%) 60 7 47% 50 40 30 20 9% 10 0 Superfluous Apology Some scholars have suggested that there may be drawbacks to issuing an apology. We did not identify any drawbacks in our investigation. Still, it is quite possible that the repeated use of superfluous apologies or the delivery of a superfluous apology that appears insincere may yield different results. Across our studies, we identify significant benefits to apologizing. Superfluous apologies represent a powerful and easy-to-use tool for social influence. Even in the absence of culpability, individuals can increase trust and liking by saying ‘‘I’m sorry’’—even if they are merely ‘‘sorry’’ about the rain. No Apology Experimental Condition Figure 6. Superfluous apology increases trusting behavior in a train station (Study 4). remorse by individuals who are obviously not culpable for a transgression (e.g., ‘‘I’m sorry about your loss, the rain, bad traffic’’). We call this type of apology a superfluous apology. Using multiple methodologies across four studies, we document that superfluous apologies increase benevolence-based and behavioral trust. The relationship between superfluous apologies and trust is mediated by perceptions of empathic concern. In a laboratory study with a behavioral measure of trust, individuals were more likely to pass money to confederate counterparts who issued a superfluous apology than to those who did not. In a video-vignette study, a superfluous apology increased benevolence-based trust relative to both a commonly used greeting and a traditional apology. In a vignette study, we find that perceptions of empathic concern mediate the effect of superfluous apologies on trust. Finally, in a field study, we find that individuals were more likely to hand over their cell phone to a stranger in a train station (our measure of trust) when they received a superfluous apology than when they did not. Although superfluous apologies increased trust in all of our studies, a number of factors may moderate the relationship between superfluous apologies and trust. For example, characteristics of the apologizer’s delivery (e.g., frequency, sincerity), internal states of the apology recipient, such as emotion (Dunn & Schweitzer, 2005), or characteristics of the apologizer or apology recipient, such as status (Lount & Pettit, 2012), may limit the effectiveness of superfluous apologies. For example, Van Kleef and De Dreu (2010) found that prosocial individuals responded generously but selfish negotiators responded exploitatively when they received an apology during a negotiation. In our studies, participants knew that the apologizer was clearly not responsible for the unfortunate circumstances participants’ faced. In practice, however, there is a continuum of culpability. This is true with respect to both the magnitude of culpability and the certainty of blameworthiness. Recent work by Gunia (2013) suggests that in ambiguous situations, when it is unclear who is to be blamed, people reward those who take blame more than those who express remorse, are evasive, or deny responsibility. It is possible that the effects we observe in these studies would be even stronger when culpability is ambiguous. Acknowledgments The authors are grateful for feedback from John C. Hershey, Adam Galinsky, Katherine Milkman, and Brian Gunia as well as valuable research assistance from Tim Flank and Jessica Chen. Declaration of Conflicting Interests The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Funding The authors thank the Wharton Ackoff Fellowship and the Wharton Behavioral Lab for research support. Notes 1. We included passing decision in earlier rounds as a covariate to account for baseline trust. Without this control, the difference between the two experimental conditions was marginally significant (p ¼ .07). 2. We also conducted a mediation analysis without collapsing the neutral and acknowledgment conditions (Preacher & Hayes, 2004). When we compared the superfluous apology condition with the acknowledgement condition, a 5000-sample bootstrap showed a standardized indirect effect of 0.27 (standard error ¼ .05, 95% bias-corrected CI [0.18, 0.36]). When we compared the superfluous apology condition with the neutral condition, a 5000-sample bootstrap showed a standardized indirect effect of 0.22 (standard error ¼ 0.04, 95% bias-correct CI [0.15, 0.32]). 3. Weather data retrieved from http://cdo.ncdc.noaa.gov/qclcd/ QCLCD Supplemental Material The online [appendices/data supplements/etc] are available at http:// XXX.sagepub.com/supplemental. References Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173–1182. Baumeister, Stillwell, & Heatherton. (1994). Guilt: An interpersonal approach. Psychological Bulletin, 115, 243–267. Berg, J., Dickhaut, J., & McCabe, K. (1995). Trust, reciprocity, and social history. Games and Economic Behavior, 10, 122–142. Bergsieker, H. B., Shelton, J. N., & Richeson, J. A. (2010). To be liked or respected: Whites’ and minorities’ divergent goals during interracial 8 interactions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 99, 248–264. Bohnet, I., & Hucks, S. (2004). Repetition and reputation: Implication for trust and trustworthiness when institutions change. American Economics Review, 94, 362–366. Butler, J. K., & Cantrell, R. S. (1984). A behavioral decision theory approach to modeling dyadic trust in superiors and subordinates. Psychological Reports, 55, 19–28. Davis, M. H. (1983). Measuring individual differences in empathy: Evidence for a multidimensional approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 44, 113–126. Dunn, J., & Schweitzer, M. (2005). Feeling and believing: The influence of emotion on trust. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88, 736–748. Engle-Warnick, J., & Slonim, R. L. (2004). The evolution of strategies in a repeated trust game. Journal of Economics Behavior and Organization, 55, 553–573. Fehr, R., & Gelfand, M. (2010). When apologies work: How matching apology components to victims’ self-construals facilitates forgiveness. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 113, 37–50. Goffman, E. (1971). Relations in public: Microstudies of the public order. New York, NY: Basic Books. Grandey, A. A. (2003). When ‘‘the show must go on’’: Surface and deep acting as determinants of emotional exhaustion and peer-rated service delivery. Academy of Management Journal, 46, 86–96. Gunia, B. (2013). The blame bias: Forgoing the benefits of blametaking. Organization Science Working paper. Haselhuhn, M. P., Schweitzer, M. E., & Wood, A. M. (2010). How implicit beliefs influence trust recovery. Psychological Science, 21, 645–648. Johnson, J. L., Cullen, J. B., Sakano, T., & Takenouchi, H. (1996). Setting the stage for trust and strategic integration in Japanese-U.S. cooperative alliances. Journal of International Business Studeis, 27, 981–1004. Kim, P. H., Dirks, K. T., Cooper, C. D., & Ferrin, D. L. (2006). When more blame is better than less: The implications of internal vs. external attributions for the repair of trust after a competencevs. integrity-based trust violation. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 99, 49–65. Kim, P. H., Ferrin, D. L., Cooper, C. D., & Dirks, K. T. (2004). Removing the shadow of suspicion: The effects of apology versus denial for repairing competence- versus integrity-based trust violations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89, 104–118. Lazare, A. (2004). On apology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. Lount, R. B., Jr., & Pettit, N. C. (2012). The social context of trust: The role of status. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 117, 15–23. MacKinnon, D. P., & Dwyer, J. H. (1993). Estimating mediated effects in prevention studies. Evaluation Review, 17, 144–158. Maddux, W. W., Kim, P. H., Okumura, T., & Brett, J. M. (2011). Cultural differences in the function and meaning of apologies. International Negotiation, 16, 405–425. Social Psychological and Personality Science 00(0) Malhotra, D., & Murnighan, J. K. (2002). The effects of contract on interpersonal trust. Administrative Science Quarterly, 47, 534–559. Mayer, R. C., & Davis, F. D. (1995). An integration model of organization trust. Academy of Management Review, 20, 709–734. Murphy, R. O., Rappaport, A., & Parco, J. E. (2006). The breakdown of cooperation in iterative real-time trust dilemmas. Experimental Economics, 9, 147–166. National Archives and Records Administration, Bill Clinton’s Yellowstone National Park, August 1995 (National Archives and Records Administration). Ohbuchi, K., Kameda, M., & Agarie, N. (1989). Apology as aggression control: Its role in mediating appraisal of and response to harm. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56, 219–227. Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2004). SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments & Computers, 36, 717–731. Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40, 879–891. Scher, S. J., & Darley, J. M. (1997). How effective are the things people say to apologize? Effects of the realization of the apology speech act. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research, 26, 127–140. Schlenker, B. R. (1980). Impression management: The self-concept, social identity, and interpersonal relations. Monterey, CA: Brooks/Cole. Schlenker, B. R., & Darby, B. W. (1981). The use of apologies in social predicaments. Social Psychology Quarterly, 44, 271–278. Schweitzer, M. E., Hershey, J. C., & Bradlow, E. T. (2006). Promises and lies: Restoring violated trust. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 101, 1–19. Tannen, D. (1996). I’m sorry, I won’t apologize. Retrieved December 18, 2010, from https://www9.georgetown.edu/faculty/tannend/ nyt072196.htm Tannen, D. (1999, April/May). Contrite makes right. Civilization, 6, 67–70. Tannen, D. (2001). You just don’t understand: Women and men in conversation. New York, NY: William Morrow. Tavuchis, N. (1991). Mea culpa: A sociology of apology and reconciliation. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. Van Kleef, G. A., & De Dreu, C. K. W. (2010). Longer-term consequences of anger expression in negotiation: Retaliation or spillover? Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 5, 753–760. Van Kleef, G. A., De Dreu, C. K. W., & Manstead, A. S. R. (2006). Supplication and appeasement in conflict and negotiation: The interpersonal effects of disappointment, worry, guilt, and regret. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 91, 124–142. Van Kleef, G. A., De Dreu, C. K. W., & Manstead, A. S. R. (2010). An interpersonal approach to emotion in social decision making: The emotions as social information model. Advances in Experimental social Psychology, 42, 45–96.