Critique of Anthropology

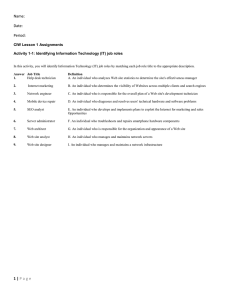

advertisement