MSU International Development Working Paper

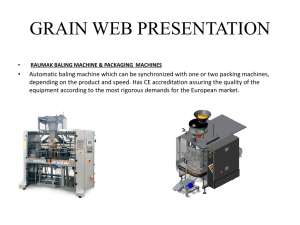

advertisement