Financing of the Terrorist Organisation Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (ISIL)

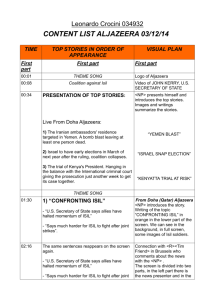

advertisement