Document 12088949

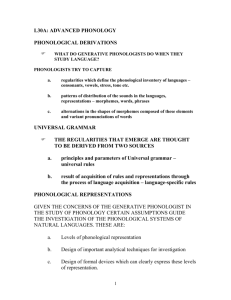

advertisement