JOB CREATION AND DESTRUCTION IN PORTUGAL*

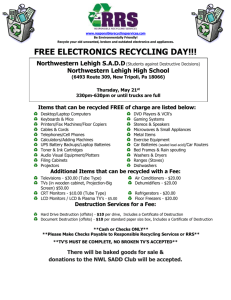

advertisement