Document 12066680

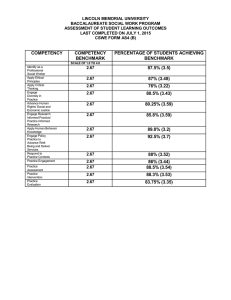

advertisement