Document 12056644

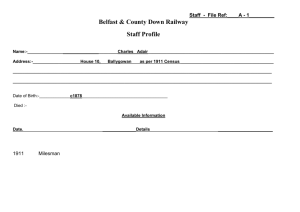

advertisement