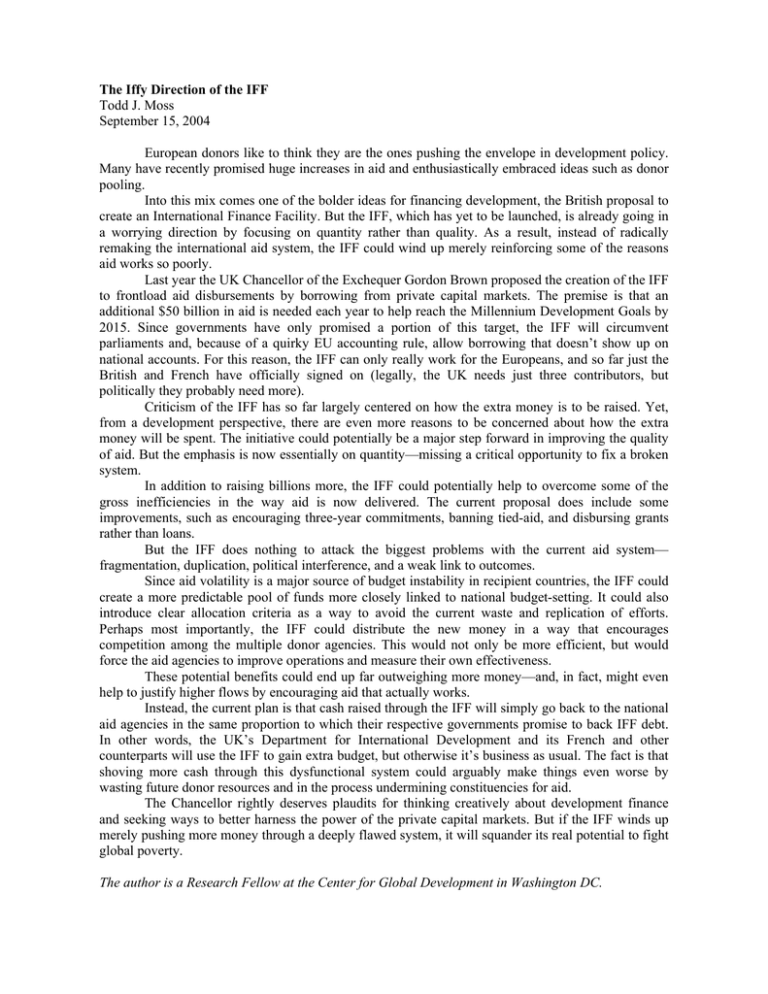

The Iffy Direction of the IFF Todd J. Moss September 15, 2004

advertisement

The Iffy Direction of the IFF Todd J. Moss September 15, 2004 European donors like to think they are the ones pushing the envelope in development policy. Many have recently promised huge increases in aid and enthusiastically embraced ideas such as donor pooling. Into this mix comes one of the bolder ideas for financing development, the British proposal to create an International Finance Facility. But the IFF, which has yet to be launched, is already going in a worrying direction by focusing on quantity rather than quality. As a result, instead of radically remaking the international aid system, the IFF could wind up merely reinforcing some of the reasons aid works so poorly. Last year the UK Chancellor of the Exchequer Gordon Brown proposed the creation of the IFF to frontload aid disbursements by borrowing from private capital markets. The premise is that an additional $50 billion in aid is needed each year to help reach the Millennium Development Goals by 2015. Since governments have only promised a portion of this target, the IFF will circumvent parliaments and, because of a quirky EU accounting rule, allow borrowing that doesn’t show up on national accounts. For this reason, the IFF can only really work for the Europeans, and so far just the British and French have officially signed on (legally, the UK needs just three contributors, but politically they probably need more). Criticism of the IFF has so far largely centered on how the extra money is to be raised. Yet, from a development perspective, there are even more reasons to be concerned about how the extra money will be spent. The initiative could potentially be a major step forward in improving the quality of aid. But the emphasis is now essentially on quantity—missing a critical opportunity to fix a broken system. In addition to raising billions more, the IFF could potentially help to overcome some of the gross inefficiencies in the way aid is now delivered. The current proposal does include some improvements, such as encouraging three-year commitments, banning tied-aid, and disbursing grants rather than loans. But the IFF does nothing to attack the biggest problems with the current aid system— fragmentation, duplication, political interference, and a weak link to outcomes. Since aid volatility is a major source of budget instability in recipient countries, the IFF could create a more predictable pool of funds more closely linked to national budget-setting. It could also introduce clear allocation criteria as a way to avoid the current waste and replication of efforts. Perhaps most importantly, the IFF could distribute the new money in a way that encourages competition among the multiple donor agencies. This would not only be more efficient, but would force the aid agencies to improve operations and measure their own effectiveness. These potential benefits could end up far outweighing more money—and, in fact, might even help to justify higher flows by encouraging aid that actually works. Instead, the current plan is that cash raised through the IFF will simply go back to the national aid agencies in the same proportion to which their respective governments promise to back IFF debt. In other words, the UK’s Department for International Development and its French and other counterparts will use the IFF to gain extra budget, but otherwise it’s business as usual. The fact is that shoving more cash through this dysfunctional system could arguably make things even worse by wasting future donor resources and in the process undermining constituencies for aid. The Chancellor rightly deserves plaudits for thinking creatively about development finance and seeking ways to better harness the power of the private capital markets. But if the IFF winds up merely pushing more money through a deeply flawed system, it will squander its real potential to fight global poverty. The author is a Research Fellow at the Center for Global Development in Washington DC.