The Foundational Document on Outreach and Engagement:

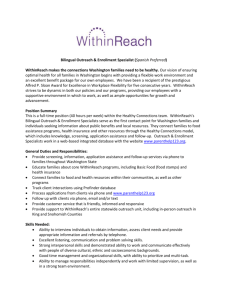

advertisement