FINAL DRAFT OCTOBER 2003

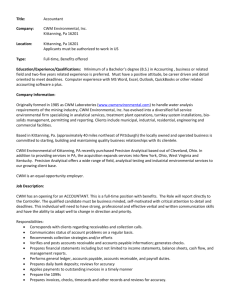

advertisement