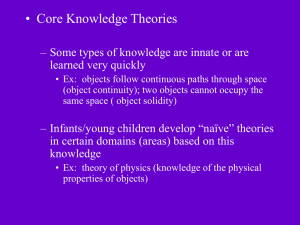

IDENTITY, AND THE OBJECT REPRESENTATION,

advertisement