Mark W. Kelley 1

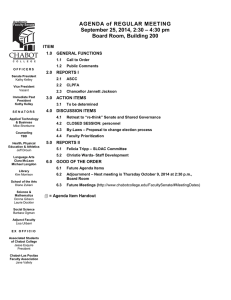

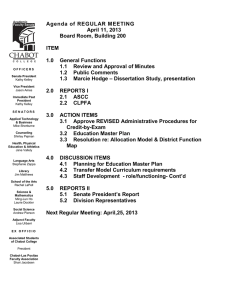

advertisement