Saskatoon’s Homeless Population 2012: A Research Report

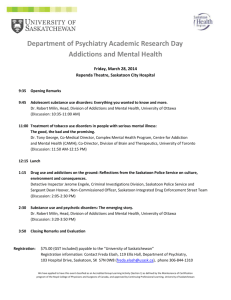

advertisement