Program Evaluation of Crisis Management Services Terra Quaife, Laurissa Fauchoux, David Mykota,

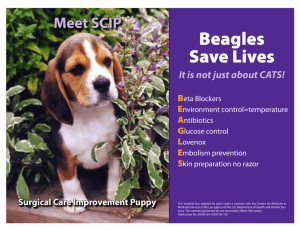

advertisement