Postpartum Depression Support Program Evaluation by Kyla Avis and Angela Bowen

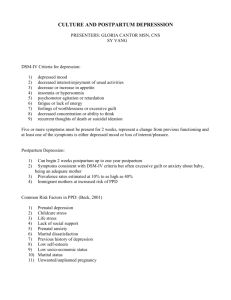

advertisement