International Students in Saskatchewan Policies, Programs, and Perspectives

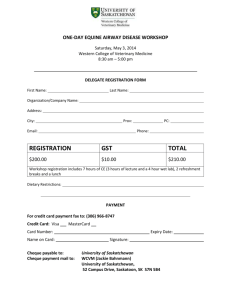

advertisement