Broadway Theatre Membership Assessment A Research Report by Cameron Moneo, Maria Basualdo,

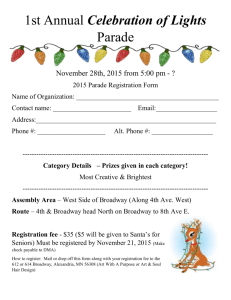

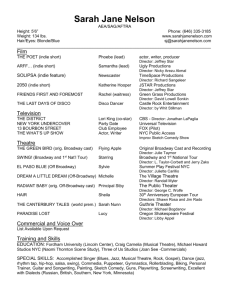

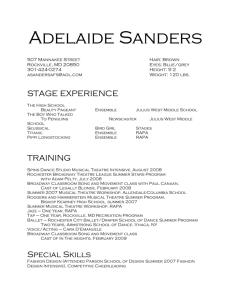

advertisement