Youth……… Youth Addictions Project ...on the brink

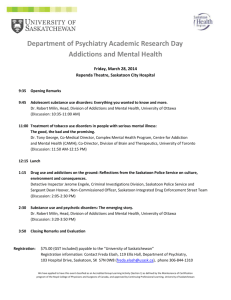

advertisement