Through the Eyes of Women During Confinement and Integration

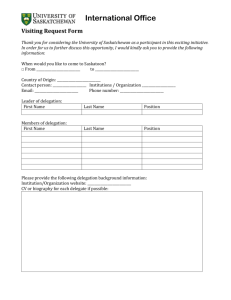

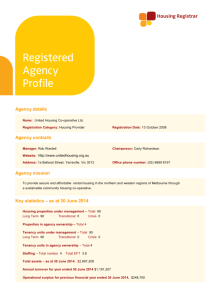

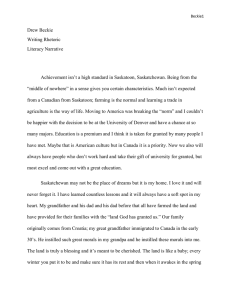

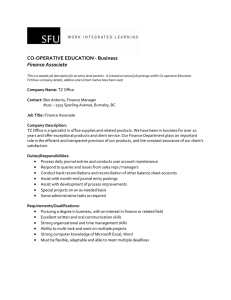

advertisement