Awareness of and Support for the Social Economy in Saskatoon

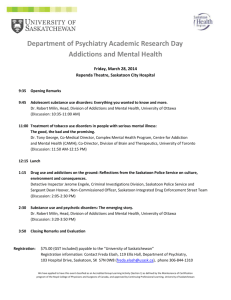

advertisement