Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., America’s Non-White Youth,

advertisement

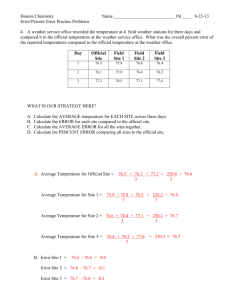

The Triple Whammy of Geographic Disadvantage Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., America’s Non-White Youth, and the Triple Whammy of Geographic Disadvantage1 James H. Johnson Jr., Ph.D. William Rand Kenan, Jr. Distinguished Professor Kenan-Flagler Business School Frank Hawkins Kenan Institute of Private Enterprise University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill 1 Invited Address, Martin Luther King Triangle Interfaith Prayer Breakfast, Sheraton Imperial Hotel, Research Triangle Park, NC, January 19, 2015. Page 1 The Triple Whammy of Geographic Disadvantage what I have come to call the triple whammy of geographic disadvantage—a circumstance that limits educational and economic opportunities of mainly Thank you very much for that most kind America’s non-white youth (see Ross, 2014; Cohen, introduction. I consider it both a high honor and 2014)--would be near, if not at, the top of Dr. a blessing to have the opportunity to share a few King’s social justice agenda were he alive today. thoughts with all of you this morning on the occaHaving studied inequality in American socision of the 2015 Triangle MLK Interfaith Breakfast. ety for more than 30 years (see Appold and Johnson, After accepting the planning commit- 2012; Bobo, Oliver, Valenzuela, & Johnson, 2000; tee’s invitation to serve as the keynote speaker Johnson, Oliver, & Bobo, 1994), I am convinced this morning, I immediately asked myself the fol- the recent egregious acts of violence and our justice lowing questions: What would keep Dr. King system’s responses to them are deeply rooted in the up at night were he alive today on this occa- hyper-segregation, educational disenfranchisement, sion of his 86th birthday? That is, what pressing and economic marginalization that continue to charissue or set of issues would take priority on Dr. acterize non-white residential life in America today King’s agenda for justice and fairness in America? (Sharkey, 2013). My assertion here is rooted, at least in part, in my experiences as an expert witness in I am certain—and sure most of you would the penalty phase of more than 50 capital murder agree--he would be deeply troubled by the very ten- cases involving males of color over the past quaruous at best, and extremely volatile at worst, state ter century (see Johnson, Farrell, & Sapp, 1997a,b). of relations between the police and the African Against this backdrop, I respectfully ask for American community in America today. I think Dr. King would be particularly aggrieved by the your indulgence as I first, briefly describe the two events surrounding the untimely and tragic deaths colorful demographic processes that undergird the of Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, Eric Garner, triple whammy of geographic disadvantage for young and Tamir Rice. And, as a staunch advocate for people of color; second, graphically illustrate the non-violent protest, I also firmly believe Dr. King nature, magnitude, and geographic scope of the three would be equally troubled by the senseless acts dimensions of the problem; and third, conclude with of violence that snuffed out the lives of the two an overview of the ameliorative strategies I believe New York City police officers this past December. Dr. King would embrace if he were still with us. 1.0 Preamble and Purpose Undoubtedly all of you can come up with 2.0 Critical Background and Context a litany of other contemporary issues that you think would probably preoccupy Dr. King’s atten- Two colorful demographic trends are dration. But for me, as demographer, I firmly believe matically reshaping U.S. communities today. Immi- Page 2 The Triple Whammy of Geographic Disadvantage gration, mainly from Asia, Latin America, and the Middle East, is contributing to the ‘browning” of America, while the aging of the U.S. native born population is contributing to the “graying” of America (Frey, 2010; Johnson, 2006, 2009; Johnson and Kasarda, 2011; Pew Hispanic Center, 2013). Emblematic of the “browning” trend, according to U.S. census data, people of color—Hispanics (15.2 million), Blacks (3.7 million), Asians (4.3 million) and other non-white groups composed mostly of people self-identifying as biracial or multiracial (1.4 million)—accounted for 92 per- cent of U.S. net population growth during the first decade of the new millennium (27 million) (Johnson and Kasarda, 2011; Pew Hispanic Center, 2013). The “graying” of the American population is driven principally by the aging of Baby Boomers—the 80 million people born between 1946 and 1964. On January 1, 2011, America’s first Baby Boomer reached the age of 65 and became eligible for a host of governmental benefits. Over the next 20 years, Boomers will continue to turn 65 at the rate of 8,000 per day and are projected to live on average another 18.7 years. Because fertility rates Figure 1 RACIAL TYPOLOGY OF U.S. COUNTIES Source: U.S. Decennial Census, 2010 Page 3 The Triple Whammy of Geographic Disadvantage dropped sharply following the post-WWII baby boom (especially among non-Hispanic whites), this increased longevity—absent a continuous flow of prime working age immigrants to support the system—will severely challenge the nation’s ability to sustain Social Security and other governmental social “safety net” programs (Johnson, 2013). will have to propel our nation forward in the years ahead--are at substantial risks of falling through the cracks of our nation’s K-12 education system and failing to acquire the requisite advanced skills through post-secondary education to compete in the unsparing global economy of the 21st century (Johnson, 2006; Johnson and Parnell, 2012; Johnson, et. al., 2015). In defense of my assertion here, allow me Moreover, the “browning” and “graying” to describe the three types of geographical sorting of of America are ushering in dramatic shifts in the the U.S. population that have created this situation. geographic distribution of the U.S. population, as well as major changes in marriage patterns, living 3.1 The First Whammy arrangements, and family and household composiFigure 1 portrays the nature and geotion (Taylor, et. al, 2010; Livingston and Parker, 2010; Tavernise, 2011; Krivickas and Lofquist, graphical extent of the problem as mani2011). These shifts create both opportunities and fested at the county level in America. It highchallenges for our nation (Johnson, et. al., 2015). lights four different county types which are a product of the nation’s shifting demography. 3.0 The Triple Whammy of Geographic Disadvantage In part as a consequence of the residential settlement patterns that undergird these two colorful processes, our nation’s nonwhite youth are increasingly concentrated in U.S. counties, cities and towns, communities and neighborhoods characterized by enormous cultural generation gaps (whammy #1), high levels of race/ethnic re-segregation (whammy #2), and extreme concentrations of poverty (whammy #3) (Craig and Richeson, 2014; Besl, 2011; Wiltz, 2014; Frey, 2011; Mather, 2007; Johnson and Lichter, 2010). Owing to this state of affairs, I contend, and believe Dr. King would concur, our nation’s nonwhite youth—the new majority that Page 4 Areas colored red in this map are “racial generation gap” counties. They form an elongated, curvilinear cluster extending from roughly Washington, DC southward along the South Atlantic Seaboard to South Florida and then turn westward winding through the Deep South and the Southwest all the way to California. There are also a few isolated clusters in the upper Midwest and the Pacific Northwest (Figure 1). In these counties, the <18 population is predominantly nonwhite, while the over 65 population is predominantly white. Prior research has shown that huge cultural/racial gaps exist in these counties (Frey, 2011; Roberts, 2007; Maher, 2007; Blackwell, 2011; Wiltz, 2014). In fiscal matters, the whites, who are mostly empty nesters, are more likely to advocate The Triple Whammy of Geographic Disadvantage for property tax cuts and retirement amenities than to lobby for additional resources for public education and other child and youth development activities (Maher, 2007; Frey, 2011; Blackwell, 2011). Because these aging empty nesters make up a majority of the voters, only limited financial support exists at the local level for the education of the predominantly minority youth in these “racial generation gap” counties. Areas highlighted in orange in Figure 1, which cluster along with the geographical distribution of the “racial generation gap” counties, are “majority-minority” counties. In contrast to the “racial generation gap” counties, the adult population (18+) and the youth population (<18) are both predominantly nonwhite in these counties. Only 17% of the youth in these counties are non-Hispanic white. As the voting age majority, nonwhite adults are more likely than resident whites to lobby for greater support for public education. But these are mostly low-wealth counties and therefore the local tax base is often too small to ensure the predominantly non-white youth a high-quality education. Areas highlighted in white in Figure 1, which are more widely dispersed throughout the U.S. than the “racial generation gap” and “majority-minority” counties, are “majority-majority” counties. The adult population and the youth population are both predominantly white in these counties. But roughly one-quarter of the youth in these counties are nonwhite. What distinguishes these counties is the level of support for education; it is much stronger, especially among whites, than in the other two types of counties. But many of the minority youth in these counties, not unlike their counterparts in the “racial generation gap” and “majority-minority” counties, attend schools that are undergoing re-segregation and thus do not fully benefit from the rich educational resources—financial and otherwise—that exist in these “majority-majority” counties. And the non-white youth who manage to attend resource-rich schools in these “majority-majority” counties typically are under-represented in the college preparatory tracks or curriculums (i.e., Honors, Advanced Placement, and International Baccalaureate programs) (CollegeBoard, 2014; Theokas and Saaris, 2013). Of the 3,144 U.S. counties and county equivalents, only five did not fit into one of the previous three county types. Both the total and <18 populations in these five counties are small, accounting for 0.0002% and 0.02% of the respective totals. I have classified these five counties in the “other” category in Figure 1. Figure 2 displays how the U.S. <18 population is distributed by race and ethnicity across these four county types. Among the nation’s 74.2 million youth, 56% reside in “majority-majority” counties— arguably the most advantageous situation—while nearly all of the balance (43%) live and attend school in either “racial generation gap” (33%) or “majorityminority” counties (10%)—arguably the least advantageous situations. The remainder of the <18 population resided in the “other” counties in this typology. Looking at the distribution of youth by race/ ethnicity across these four county types reveals the Page 5 The Triple Whammy of Geographic Disadvantage Figure 2 DISTRIBUTION OF <18 POPULATION BY RACE AND COUNTY TYPE Source: American Community Survey, 2012 magnitude and depth of the disparities in the K-12 education opportunity structure in the U.S. While only one-quarter of non-Hispanic white youth (24.6%) live in either “racial generation gap” or “majority minority” counties, 62% of black youth, 73% of Hispanic or Latino youth, 63% of Asian youth, 50% of other race youth, and 49% of mixed race youth reside in these types of counties. Only 38% of America’s black youth, 27% of Hispanic youth, and 36% of Asian youth attend school in “majority-majority” counties. Youth of other races and mixed races attend schools in “majority-majority” counties at higher rates— 47% and 51%, respectively—but their absolute numbers are much smaller (1.0 million and 4.2 million, respectively) than those of Black (10.4 million), Hispanic (17.1 million), and Asian (3.2 million) youth. Page 6 3.2 The Second Whammy Making matters worse, a significant share of America’s youth is growing up in neighborhoods that are hyper-segregated -- that is, separate and unequal (Massey and Denton, 1993; Wilson, 1987; Massey, 2007; Sharkey, 2013). To illustrate the impact of this demographic dynamic on the nation’s <18 population, I classified U.S. census tracts—census bureau-defined geographic units that approximate residential neighborhoods—by levels of segregation. Building on prior research, I classified census tracts that were 60% or more white and census tracts that were 60% or more non-white as hyper-segregated (Massey and Denton, 1993). Census tracts falling in The Triple Whammy of Geographic Disadvantage Figure 3 U.S. RACIAL SEGREGATION BY CENSUS TRACT, 2010 Source: U.S. Decennial Census, 2010 Figure 4 RACE/ETHNIC SEGREGATION OF NEIGHBORHOODS BY LEVEL OF SEGREGATION Source: U.S. Decennial Census, 2010 Page 7 The Triple Whammy of Geographic Disadvantage between these two extremes were classified as racially/ ethnically mixed or transitional neighborhoods. Figure 3 illustrates the level of racial segregation that exists in the U.S. Paralleling the distribution of “majority/majority” counties in Figure 1, large swaths of the nation are made up of predominantly white neighborhoods. The predominantly non-white and mixed neighborhoods in Figure 3 parallel the distribution of “racial generation gap” and “majority/minority” counties in Figure 1. Looking at all youth, about sixty percent live in predominantly white neighborhoods, about 28% live in predominantly nonwhite neighborhoods, and 12% reside in mixed neighborhoods—as displayed in Figure 4. Disaggregating the data by race/ethnic- ity revealed the extent to which hyper-segregation is experienced by our youth. In comparison to their distribution nationally, white children are grossly overrepresented in predominantly white neighborhoods and grossly under-represented in predominantly nonwhite and mixed neighborhoods. The opposite is true for non-white children: they are over-represented in non-white and mixed neighborhoods and underrepresented in predominantly white neighborhoods. Black and Latino youth, as Figure 5 shows, are more likely than other youth to live in hypersegregated minority neighborhoods. Nearly sixty percent of Black and Latino children reside in neighborhoods that are sixty percent of more non-white. Asian and other race children are more evenly distributed between predominantly white and predomi- Figure 5 DISTRIBUTION OF <18 POPULATION BY RACE/ETHNICITY AND NEIGHBORHOOD RACIAL COMPOSITION Source: U.S. Decennial Census, 2010 Page 8 The Triple Whammy of Geographic Disadvantage nantly non-white neighborhoods. And mixed race children are more likely to live in predominantly white than either predominantly non-white or mixed neighborhoods—not surprising given the high rates of out-marriage among Hispanics and whites and among Asians and whites (Taylor, et al., 2010). 3.3 The Third Whammy as extreme-poverty neighborhoods. Those with youth poverty rates in the 25% to 39% range were labeled high-poverty neighborhoods. And those with youth poverty rates below 25% were labeled as low-poverty neighborhoods (Wilson, 1987). The resulting geographical distribution appears in Figure 6 and the racial/ethnic composition of these three types of neighborhoods is illustrated in Figure 7. Further complicating matters, America’s nonwhite youth also are increasingly isolated in neighborhoods characterized by extreme and high poverty -- that is, economically marginalized. I employed a three-tier classification to assess U.S. youth exposure to poverty: census tracts in which 40% or more of the <18 population lived in households with incomes below the poverty level were labeled Concentrated-poverty neighborhoods (i.e., extreme- and high-poverty areas) cluster mainly in states experiencing the most rapid population growth since 2000. For the most part, those states are in the South and West regions (see Johnson, et.al., 2015). Moreover, as Figure 7 shows, these areas of concentrated poverty tend to be disproportionately Black and Latino. Low-poverty areas are over- Figure 6 U.S. <18 POPULATION POVERTY BY CENSUS TRACT, 2010 Source: U.S. Decennial Census, 2010 Page 9 The Triple Whammy of Geographic Disadvantage Figure 7 RACE/ETHNIC COMPOSITION OF NEIGHBORHOODS BY <18 POPULATION POVERTY STATUS Source: U.S. Decennial Census, 2010 Figure 8 DISTRIBUTION OF <18 POPULATION BY RACE/ETHNICITY AND NEIGHBORHOOD POVERTY STATUS Source: U.S. Decennial Census, 2010 Page 10 The Triple Whammy of Geographic Disadvantage Figure 9 FOOD DESERTS AND FOOD INSECURITY whelmingly non-Hispanic white with above aver- the requisite resources and supports for healthy age concentrations of Asian and mixed race youth. child and youth development (Wilson, 1987; Massey and Denton, 1993; Sharkey, 2013). These are, for Examining the poverty problem from the example, neighborhoods where food deserts—areas youth as opposed to the neighborhood perspective, where residents have no car and no supermaras is done in Figure 8, the majority of our nation’s <18 ket within a mile of where they live--are prevalent population (70 percent) live in areas with low rates of and food insecurity is all too common (American child and adolescent poverty. Only 13% live in extreme Nutrition Association, 2011), as shown in Figure 9. poverty and 17% lived in high poverty areas. However, these aggregate statistics mask a pernicious race/ Consistent with my notion of the triple ethnic divide in the economic wellbeing of our youth. whammy of geographic disadvantage, there is a high degree of overlap in the geographical distributions of While 85% of Asian, 82% of White, and the “racial generation gap” and “majority minority” 71% of mixed race children live in low poverty counties in Figure 1, the hyper-segregated, predomiareas (many of these areas are actually neighbor- nantly nonwhite neighborhoods in Figure 3, and the hoods of concentrated affluence), 52% of Black, extreme and high-poverty neighborhoods in Figure 44% of Latino, and 43% of other race children 6. The visual correlations across these three geolive in areas of either extreme poverty or high pov- graphical contexts are abundantly clear in Figure 10. erty—areas that research has shown typically lack Page 11 The Triple Whammy of Geographic Disadvantage Figure 10 THE TRIPLE WHAMMY OF GEOGRAPHIC DISADVANTAGE Source: U.S. Decennial Census, 2010 In Table 1, I have classified America’s youth from the most vulnerable to the least vulnerable across these three geographical contexts. Colorcoded red, the most vulnerable youth—an estimated 9.8 million--are exposed to all three levels of the triple whammy of geographic disadvantage. Colored coded orange, an estimated 12.2 million youth are exposed to two out of the three levels of geographical disadvantage. Color-coded yellow, 20.0 million youth are exposed to only one out of the three levels of geographical disadvantage. personal and institutional networks that are keys to ascertaining a high quality education. This latter group, it might be argued, benefits from the triple whammy of geographical advantage. How would Dr. King likely respond to these demographically driven education challenges. I think he would draw heavily from the following research findings, which are taken from a forthcoming paper prepared by my research colleagues and I (Johnson, et al., 2015), to frame his response. Color-coded light gray, the least vulnerable youth—an estimated 34.1 million—do 4.0 Responding to Demographicallynot reside in any of these three disadvantaged geoDriven K-12 Education Challenges graphical situations. Rather, they reside in more prosperous counties and neighborhoods with not Recent research conducted by the Center on only the financial resources but also the diverse Budget and Policy Priorities revealed that 35 states Page 12 The Triple Whammy of Geographic Disadvantage Table 1 DISTRIBUTION OF <18 POPULATION BY COMMUNITY TYPE Source: U.S. Decennial Census, 2010 Page 13 The Triple Whammy of Geographic Disadvantage are providing less funding for K-12 education today (2013-14) than they were six years ago prior to onset of the Great Recession in 2008 (Leachman and Mai, 2014). Based on the data compiled in Figures 1, 3, and 6 and summarized in Figure 10, fifteen of the states cutting funding for K-12 education have significant concentrations of young people who are facing one or more levels of geographic disadvantage. Since 2008, the funding cuts have exceeded 20% in two of these states (OK & AL), 10% to 17% in nine of the states (AZ, KS, SC, GA, CA, MS, VA, NM, TX), and between 4% and 9% in the remaining four states (LA, AR, NC, CO) (Figure 11). These cuts are especially challenging because nationally on average about 44% of total education spending comes from the states (actual percentages vary from state to state). Leachman and Mai (2014) have articulated in a succinct and sobering way the options local school districts with significant concentrations of vulnerable young people have in addressing state level budget cuts. They note that: “[c]uts at the state level mean that local school districts have to either scale back the educational services they provide, raise more local tax revenue to cover the gap, or both.” However, they go on to assert that “[l]ocal school districts typically have little ability to replace lost state aid on their own.” This is especially the case in the communities where the 9.8 million young people face the triple whammy of geographic disadvantage. I compare the characteristics of communities in which youth have the triple whammy of geographical advantage and two instances in which youth have the triple whammy of geographical disadvantage in Table 2 to illustrate the point. Major disparities exist in educational attainment, labor force participation, mean usual hours worked, unemployment rates, median income, homeownership rates, and home values across these three types of communities. As a consequence, the real estate taxes paid--typically the primary source of funding for public education--are much lower in the two triple whammy geographically disadvantaged communities ($1,240 and $1,955, respectively) than they are in the triple whammy geographically advantaged community ($2,218). out, Moreover, as Leachman and Mai (2014) point Given the still weak state of many of the nation’s real estate markets, many school districts struggle to raise more money from the property tax without raising rates, and rate increases are politically very difficult [especially in “racial generation gap” and “majority/minority” communities].1 In addition, owing to higher levels of adult educational attainment and employment, triple whammy geographically advantaged communities are better positioned than their more geographically disadvantaged counterparts to leverage personal, private, and/or philanthropic sources of capital to fill schoolbased funding gaps (Nelson and Grazley, 2014). It is against this backdrop that K-12 school leaders, especially those in districts where young people are constrained by the triple whammy of geographical disadvantage, must be able to make both the demographic case and the business case for continuing support for K-12 education. That Leachman and Mail note further that “Localities collected 2.1 percent less in property tax revenue in the 12 month period ending in March 2013 than in the previous year, after adjusting for inflating.” 1 Page 14 The Triple Whammy of Geographic Disadvantage Figure 11 PERCENT CHANGE IN SPENDING PER STUDENT, INFLATION-ADJUSTED, 2008-2014 Sources: CBPP budget analysis and National Center for Education Statistics enrollment estimates is, they have to help policymakers and other key stakeholders understand the link between societal aging on the one hand and the browning of the school-age population on the other (Johnson, 2013). Arguing that this is the human capital asset base that will have to propel our nation forward in the coming decades, I have asserted elsewhere that the specific pitch must go something like this (Johnson, 2013): Because of the huge wave of boomers who will be exiting the labor market over the next 20 years, we simply cannot thrive and prosper as a nation in the hyper-competitive global economy of the 21st century if we do not embrace immigrant newcomers and continue to invest in our increasingly more diverse school age population. And if we are not globally competitive as a nation, we will not be able to build the economy that will help to sustain the social safety net programs that serve sen- Page 15 The Triple Whammy of Geographic Disadvantage iors and other vulnerable populations. In other words, school leaders must convince policymakers and foundation executives as well as the general public that it is a form of enlightened self-interest for us—all of us—to invest in our young people. In attempting to successfully educate the increasingly demographically diverse clientele of students described above, K-12 education institutions are typically long on mission and vision but short on strategy. And most interventions that are designed to improve educational and other outcomes for our most vulnerable or disadvantaged youth typically operate on an “everything is wrong with you and I am going to fix it” deficit model (Glazer and Moynihan, 1963; Kunjufu, 1990; Anderson, 1990; Miller, 1996; Jackson and Moore, 2008). As Noguera (1997) points out, this approach treats race and gender as explanatory factors, “resulting in an explanation of the crisis facing [disadvantaged youth] which focuses almost exclusively on cultural rather than structural factors.” He goes on to note that By focusing almost exclusively on race and gender, other factors which may be relevant to understanding the causes of social problems like . . . [poor] student performance . . . often go ignored. Most important among the omitted factors are the influence of class and geographic location. Other research has demonstrated that deficitbased solutions typically involve punitive strategies (e.g., get tough on crime and education policies) that in retrospect have been shown to have a disparate impact on disadvantaged youth, especially males of color (Grant and Johnson, 1995; Page 16 Miller, 1996; Johnson and McDaniel, 2011). To effectively address the triple whammy of geographic disadvantage, K-12 education leaders must eschew the deficit model and embrace instead an education intervention model anchored in research on successful pathways in children’s development (Weisner, 2005; Cooper, et. al., 2005). Acknowledging that not all children who grow up in dysfunctional families and economically distressed environments fail academically and in other walks of life (Jarrett, 1995), this body of research strives to identify the culturally-specific, social and environmental determinants or pathways to success. Two particularly salient findings have emerged from the successful pathways research. The first is that disadvantaged youth whose daily routines involve sustained engagement in activities in a mediating institution in their local environment, such as the YMCA, YWCA, and the Boys and Girls Club, are far more likely to be successful than their counterparts who are not involved in such institutions (Jarrett, 1995; Putnam, 2004). Such entities are called “mediating institutions” because they discourage disadvantaged youth from engaging in dysfunctional or anti-social behaviors and encourage them to pursue mainstream avenues of social and economic mobility (Johnson and Oliver, 1992; Jarrett, 1995; Fernandez-Kelly, 1995). The second is that disadvantaged youth who are embedded in personal networks outside their local neighborhoods—often characterized as connected youth—are far more likely to succeed academically and in other walks of life than youth The Triple Whammy of Geographic Disadvantage whose networks are limited to the local neighborhood environments—often referred to as isolated youth. Connected youth are able to draw upon what is referred to as “bridging” social capital—a geographically, racially or ethnically, and economically diverse set of ties which enhance their knowledge base and opportunities for upward mobility. Isolated youth, such as those identified above as growing up in racial generation gap and majority/minority counties as well as neighborhoods characterized by hyper-segregation and concentrated poverty (see Figure 10), have to rely primarily on what is known as “bonding” social capital—a geographically and otherwise limiting network of individuals who share similar characteristics and circumstances and thus do not significantly enhance their knowledge or opportunities for advancement (Coleman, 1988; Fernandez-Kelly, 1995; Jarrett, 1995; Putnam, 2004). Before constructive education strategies can be developed at the school district level, I believe pre-k through grade 12 teacher education and professional development programs must be re-engineered to reflect the changing demography, cultural backgrounds, and living arrangements of the school age population (Bevan, 2013; Krivickas and Lofquist, 2011; Hutchinson, 1999; Fraser, 1998; Huston, McLoyd, and Coll, 1994; Heath and McLauglin, 1993). Currently, the problem, at the most basic level, is a fundamental lack of teacher knowledge and understanding of the critical risk factors that students from increasingly diverse backgrounds face at various stages of the life course between birth and late adolescence. More specifically, problems arise when teachers do not understand and appreciate the cultural background, language, values, and home environments of their students. Without the benefit of this crucial information and a portfolio of strategies to capitalize on their students’ strengths and address known risk factors, teachers, not unlike hiring agencies and prospective employers, often view their students, especially students of color, through negative stereotypical lenses (Kirschenman and Neckerman, 1991). Among both educators and employers, research shows, for example, that black males are often viewed categorically as lazy, inarticulate, uneducable, un-trainable, and most importantly, dangerous—and therefore unworthy of substantial investments of time and energy to develop and/or hone their skills (Wilson, 1987; Johnson, Farrell, and Stoloff, 2000; Moss and Tilly, 1996; Miller, 1996). In short, success-based approaches, in contrast to deficit-based interventions, focus on constructive strategies that can be employed to help vulnerable youth navigate or overcome structural constraints they face in their daily lives (Johnson, Farrell, and Stoloff, 2000). Building upon this body of research, it is therefore essential that K-12 leaders transform schools from educational to mediating institutions, especially in communities that lack youth serving organizations, and develop effective strategies to create bridging social capital for children growing up in racially or ethnically and economically isolated environments. While it is very difficult, if not impossible, to socially engineer integration in our public schools, creating diverse and globe-spanning networks for Addressing the crisis in American education, all, and especially our most vulnerable, youth are especially the racial achievement gaps, requires a eminently achievable in the current digital age. radical restructuring of the content of both higher Page 17 The Triple Whammy of Geographic Disadvantage Table 2 AMERICAN YOUTH FACING THE TRIPLE WHAMMY OF GEOGRAPHIC ADVANTAGE AND DISADVANTAGE Source: U.S. Decennial Census, 2010 education programs for aspiring teachers and in service professional development programs for existing teachers. Building a bridge to success for an increasingly diverse student clientele, I contend, requires greater emphasis in teacher education and professional development programs in six disparate but related theoretical domains and research paradigms—successful pathways theory, critical race theory, emotional regulation theory, race/cultural identity theory, resiliency theory, and oppositional culture theory—which are summarized in Table 3 (Johnson and McDaniel, 2011). These theories underscore the resiliency and strengths that our increasingly diverse student body possess which need to be incorporated Page 18 in classroom instruction and teachers’ interactions and relationships (or lack thereof) with various subgroups of the school age population (e.g., black males). Training and professional development can lead to effective intervention models and curricular strategies and innovations to overcome achievement gaps that exist across the multiple geopolitical contexts and settings that America’s youth, as described earlier, live and attend school in today. We—my research colleagues and I--have developed a prototype professional development program for the key influencers in the lives of school age children (see Figure 12) and a school-based successful pathways to opti- The Triple Whammy of Geographic Disadvantage Figure 12 A PROTOTYPE PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT PROGRAM Source: Authors Figure 13 SUCCESSFUL PATHWAYS TO OPTIMAL DEVELOPMENT FOR MALES OF COLOR GRADES K-12 Source: Authors Page 19 The Triple Whammy of Geographic Disadvantage Table 3 CRITICAL DOMAINS FOR PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT Source: Johnson and McDaniel (2011) Page 20 The Triple Whammy of Geographic Disadvantage mal child development logic model (see Figure 13). Both models are evidence based, that is, theoretically grounded and empirically anchored in the latest research on how multiple and overlapping ecological factors and environmental stressors can impede learning. Both models build bridges to the educational mainstream through interventions and operating principles which are anchored in four core values—affection, protection, correction, and connections—that research suggests are critical to optimal development for all, but especially our most vulnerable, children. And both models are being beta-tested in a lab school—Global Scholars Academy--we have created for vulnerable children in an impoverished section of Durham, North Carolina.2 In order for models such as the ones we have developed to succeed, school leaders, to paraphrase Good to Great author Jim Collins (2001), will have to ensure that all school personnel are metaphorically on the bus, in the right seat, headed in the right direction with the interventions and strategies that undergird the models. Here school leaders can potentially benefit from the power of collective ambition approach that some private sector corporations used to weather uncertainty and continued to perform profitably during the economic downturn of the late 2000s (Ready and Truelove, 2011). Collective ambition, according to Ready and Truelove (2011, pp. 4-5), is a term used to summarize “...how leaders and employees think about why they exist, what they hope to accomplish, how they will collaborate to achieve their ambition, and how their brand promise aligns with their core values.” Ready and Truelove (2011, p. 5) note further that companies that embrace this paradigm “don’t fall into the trap of pursuing a single ambition, such as profits; instead, their employees collaborate to shape a collective ambition that supersedes individual goals and takes into account the key elements required to achieve and sustain excellence.” There are, according to Ready and Truelove (2011, p. 5), seven elements to an organization’s collective ambition, which can be summarized as follows: 1. Purpose: the organization’s reason for being or core mission. 2. Vision: the status the organization aspires to achieve within a reasonable or specified timeframe. 3. Targets and Milestones: metrics used to assess progress toward vision. 4. Strategic and Operational Priorities: actions taken or not taken in pursuit of the organization’s vision. 5. Brand Promise: commitments to stakeholders regarding the experience the organization will provide. 6. Core Values: the organization’s guiding principles, which dictate what it stands for in good time and bad. 7. Leader Behaviors: how leaders act on a daily basis as they seek to implement the organization’s vision and strategic priorities, strive to fulfill the Information about Global Scholars Academy (GSA), our laboratory school, can be accessed at www.globalscholarsacademy.org. GSA is part of a much broader set of initiatives we have designed to address child and youth development challenges throughout the life course. Information about the broader set of activities and initiatives is available at www.bridge2success.org. 2 Page 21 The Triple Whammy of Geographic Disadvantage brand promise, and live up to its core values. To achieve collective ambition, companies typically focus on two priorities: collaborative engagement of all key stakeholders and disciplined execution of the strategic roadmap for change (Ready and Truelove, 2011). The former is the glue and the latter is the grease that leads to successful outcomes. My research colleagues and I think this is the ideal framework for K-12 education leaders to embrace in their efforts to weather funding uncertainties, disruptive demographic trends, and political gridlock at various levels of government. 5.0 Conclusion Based on the evidence I have marshalled here, I believe Dr. King would conclude that the vision of America he articulated ever so eloquently in his “I Have a Dream” speech at the Lincoln Memorial during the 1963 March on Washington remains elusive—a dream deferred. With so many mainly nonwhite youth who, through no fault of their own, are denied access to a well-funded, high quality, world class education, Dr. King would probably repeat one of the most powerful and memorable themes in his “I Have a Dream” speech: Our children should not be judged by the color of their skin, but, rather, by the content of their character. Notwithstanding the well documented uneasiness that exists among non-Hispanic whites about the disruptive demographic trends that undergird the “browning” of America (Craig and Richeson, 2014), Dr. King probably would assert that educating the next generation of young people who will have to propel our nation in the international marketplace is indeed a mission that is possible. Page 22 But, in all likelihood, he also would hasten to add that, given existing political realities, it is important to frame these education challenges not solely as social or moral imperatives; but, also, and perhaps more importantly, as competitiveness issues for our nation in the highly volatile global economy of the 21st century (Johnson and Appold, 2014). Finally, in a gallant effort to mobilize the U.S. citizenry around these issues, he would say enhancing educational outcomes for our most vulnerable youth will not only improve the attractive of our nation as a place to live and do business; it also will go a long way toward ensuring that all of God’s children have equal access to opportunity in America. The Triple Whammy of Geographic Disadvantage 6.0 References Cited American Nutrition Association, 2011. “USDA Defines Food Deserts.” Nutrition Digest, 36(4), available at ht t p ://a m e r i c a n n u t r i t i o n a s s o c i a t i o n . o r g / n e w s l e t t e r /u s d a - d e f i n e s - f o o d - d e s e r t s . Cohen, Patricia, 2014, “For Recent Black College Graduates, A Tougher Road to Employment,” The New York Times, December 24, available at http://www.nytimes.com/2014/12/25/ b u s i n e s s/f o r - r e c e n t- b l a c k- c o l l e g e - g r a d u a t e s - a - t o u g h e r - r o a d - t o - e m p l oy m e n t . h t m l Coleman, James, 1988. “Social Capital in Anderson, Elijah, 1990. Streetwise: the Creation of Human Capital,”American of Sociology, 94, 95-120. Race, Class, and Change in an Urban Journal Community. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. CollegeBoard. 2014, February. The 10th Annual AP Besl, J., 2011. Racial and Eth- Report to the Nation. http://media.collegeboard. nic Diversity from the Bottom Up. The com/digitalServices/pdf/ap/rtn/10th-annual/10thCommunity Research Collaborative Blog, available at annual-ap-report-to-the-nation-single-page.pdf ht t p://crcblog.t y pepad.com/crcblog/rac i a land-ethnic-diversity-from-the-bottom-up.html Collins, J. C., 2001. Good to Great: Why Some Companies Make the Leap and Bevan, Bronwyn, 2013. Lost Opportuni- Others Don’t. New York: Harper Collins. ties: Learning in Out-of-School Time. Springer, Retrieved from http://download.springer.com/static/pdf/939/ bok%253A978-94-007-4304-5.pdf?auth66=1407021 220_2431817c91448807290e25909fa2d61f&ext=.pdf Blackwell, Angela Glover, 2011. “Is Our Racial Gap Becoming a Generation Gap?,” Huffington Post, July 14, Retrieved from h t t p : // w w w . h u f f i n g t o n p o s t . c o m / a n g e l a- g love r -bl ack we l l/is- ou r -r ac i a lgapbecomin_b_897483.html Cooper, C.R., Coll, C.G., Bartko, W.T., Davis, H.M., & Chatman, C., (Ed), 2005. Developmental Pathways Through Middle Childhood: Rethinking Contexts and Diversity as Resources. Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers. Craig, M. A., Richeson, J. A., 2014. On the Precipice of a “Majority-minority America: Perceived Status Threat from the Racial Demographic Shift Affects White Americans’ Political Ideology. Psychological Science, 3. Retrieved from http://pss.sagepub.com/content/ early/2014/04/02/0956797614527113.full.pdf+html Bobo, Lawrence, Oliver, Melvin L., Valenzuela, Abel, Fernandez-Kelley, P., 1995. Social and Cultural & Johnson, James H., Jr., 2000, Prismatic Metropolis: Capital in the Urban Ghetto: Implications for the Inequality in Los Angeles. New York, Russell Sage. Economic Sociology of Immigration. In A. Portes Page 23 The Triple Whammy of Geographic Disadvantage (Eds.), The Economic Sociology of Immigration Jackson, Jerlando F. L. and Moore, James (pp.213-247). New York: Russell Sage Foundation. L., III, 2008. “The African American Male Crisis in Education; A Popular Media InfatuFraser, Mark (ed.), 1998. Risk and Resilience ation or Needed Public Policy Response,” in Childhood. Washington, DC: NASW Press. American Behavioral Scientist, 51 (3), 847-853 Frey, W. 2011. “Counting Consequences,” National Conference of State Legislatures Magazine. Retrieved Jarrett, R. (1995). “Growing Up Poor: The Family from http://www.ncsl.org/Portals/1/Docu- Experiences of Socially Mobile Youth in Low ments/magazine/articles/2011/SL_1211Census.pdf Income African American Neighborhoods.” Journal of Adolescent Research, 10. 111-135. Frey, W., 2010. “Baby Boomers and the New Demographics of America’s Seniors.” Journal of Johnson, James H., Jr., Oliver, Melvin L., the American Society on Aging, 34 (3), 28-37. & Bobo, Lawrence, 1994, “understanding Retrieved from http://www.frey-demographer. the Contours of Deepening Urban Inequalorg/reports/R-2010- 1_Gens_34_3_p_28_37.pdf ity,” urban Geography, Vol. 15, pp. 77-89. Glazer Nathan and Moynihan, Daniel Patrick, 1963. Beyond the Melting Pot: The Negroes, Puerto Ricans, Jews, Italians, and Irish of New York City. Cambridge, MA: the M.I.T. Press and Harvard University Press. Johnson, James H., Jr., Farrell, Walter C., Jr., & Sapp, Marty, 1997a, “African American Males and Capital Murder: A Death Penalty Mitigation Strategy,” Urban Geography, Vol. 18, pp. 403-433. Grant, D. & Johnson, J. H., Jr., 1995. “Conservative Policy-Making and Growing Urban Inequality in the 1980s.” In R. Ratliff, M. Oliver, & T. Shapiro (Eds.). Research in Politics and Society (pp. 127-160). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press. Johnson, James H., Jr., Farrell, Walter C., Jr., and Sapp, Marty, 1997b. “A Contextualized Death Penalty Mitigation Strategy: Evidence from the State of North Carolina vs. Daniel Green, aka As-Saddiq Al-Amin U’Allah,” Negro Education Review, Vol. XLVII, pp. 94-115. Heath, S. B., & McLaughlin, M. W., 1993. Identity and Inner-City Youth: Beyond Ethnicity and Gender. Johnson, James H., Jr., 2013, “The Demographic Case New York: Teachers College, Columbia University. for Immigration Reform.” Ripon Forum, 47(3), 17-18. Huston, A., McLoyd, V., and Garcia Coll, C., 1994. “Children and Poverty,” Child Development, Vol. 65, pp. 275-282. Hutchinson, Elizabeth D., 1999, Dimensions of Human Behavior: The Changing Life Course. Pine Forge Press. Page 24 Johnson, J. H., Jr. and Appold, S.J., 2014. Demographic and Economic Impacts of International Migration to North Carolina. Frank Hawkins Kenan Institute of Private Enterprise and NC Bankers Association, April 15. . The Triple Whammy of Geographic Disadvantage Johnson, H. H., Jr. and Parnell, A., 2012, North Carolina in Transition: Demographic Shifts during the First Decade of the New Millennium. Chapel Hill: Frank Hawkins Kenan Institute of Private Enterprise, Kenan-Flagler Business School, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Johnson, J. H., Jr. and Kasarda, J. D., 2011. Six Disruptive Demographic Trends: What Census 2010 Will Reveal. Chapel Hill: Frank Hawkins Kenan Institute of Private Enterprise, KenanFlagler Business School, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Johnson, J. H., Jr., 2009. “Changes on the Horizon for Postsecondary Education.” Career Education Review. 9-13. Johnson, J.H., Jr., 2006. “People on the Move: Implications for U.S. Higher Education.” The College Board Review, 209, 49-48. Johnson, James H., Jr. & McDaniel, M. 2011. The Minority Male Bridge to Success Project. Chapel Hill, NC: Frank Hawkins Kenan Institute of Private Enterprise, Kenan-Flagler Business School, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Johnson, J. H., Jr., & Oliver, M. L. 1992. Structural Changes in the U.S. Economy and Black Male Joblessness: A Reassessment. In G. E. Peterson & W. Vroman (Eds.), Urban Labor Markets and Job Opportunity. (pp. 113-147). Washington, DC: The Urban Institute Press. Johnson, J.H., Jr., Farrell, W.C., Jr., & Stoloff, J.A., 2000. “An Empirical Assessment of Four Perspectives on the Declining Fortunes of the African American Male,” Urban Affairs Review, Vol. 35, No 5, pp. 695-716. Johnson, J.H., Jr., et. al., 2015. “Disruptive Demographics, the Triple Whammy of Geographic Disadvantage, and Future of K-12 Education in America,” in Educational Leadership Where We’ve Been, Where We’re Going: Dimensions of Research, Policy, and Practice, edited by Bruce A. Jones and R. Anthony Rolle, forthcoming. Johnson, K.M. & Lichter, D. T., 2010. “Growing Diversity among American’s Children and Youth: Spatial and Temporal Dimensions.” Population and Development Review, 36, available at h t t p : // o n l i n e l i b r a r y . w i l e y . c o m / doi/10 .1111/j.172 8 - 4 457. 2 010 . 0 032 2 . x/p d f Kirschenman, J. & Neckerman, K. 1991. We’d Love to Hire Them, But . . . The Meaning of Race for Employers. In C. Jencks & P. Petersen (Eds.), The Urban Underclass, 203-234 . Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution. Krivickas, K. M. & Lofquist, D. (2011-November). Demographics of Same-Sex Couple Households with Children. Fertility and Family Statistics Branch, U.S. Census Bureau, SEHSD Working Paper. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/hhes/samesex/files/Krivickas-Lofquist%20PAA%202011.pdf Kunjufu, Jawanza, 1990. Countering the Conspiracy to Destroy Black Boys, Vols. I, II, and III. Publisher: African American Images. Leachman, M. & Mai, C. 2014. Most States Funding Schools Less Than before the Recession. Page 25 The Triple Whammy of Geographic Disadvantage Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. Retrieved htt p://w w w.pewh ispan ic.org/f i les/2013/01/ from http://www.cbpp.org/files/9-12-13sfp.pdf s t a t i s t i c a l _ p o r t r a i t _ f i n a l _ j a n _ 2 9 . p d Livingston, G. & Parker, K. 2010. Since the Start of the Great Recession, More Children Raised by Grandparents. Pew Research Social and Demographic Trends. Retrieved from http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2010/09/09/since-the-start-of-the-greatrecession-more-children-raised-by-grandparents/ Putnam, Robert D. 2004. Democracies in Flux: The Evolution of Social Capital in Contemporary Society. New York: Oxford University Press. Ready, D. A. & Truelove, E., 2011. The Power of Collective Ambition. Harvard Business Review, December, available at Massey, D. & Denton, N. 1993. American Apart- http://static.ow.ly/docs/The%20Power%20of%20 heid: Segregation and the making of the Under- Collect ive%20Ambit ion%2012-2011_qwq.pdf class. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Massey, D. 2007. Categorically Une- Roberts, Sam, 2007, “New Demographic Racial qual: The American Stratification System. Gap Emerges,” The New York Times, May 18, New York: Russell Sage Foundation. available at http://www.nytimes.com/learning/ teachers/featured_articles/20070518friday.html Mather, M. 2007 .”The New Generation Gap.” Population Reference Bureau, http://www.prb.org/Pub- Ross, Janell, 2014, “For Black Kids in America, A lications/Articles/2007/NewGenerationGap.aspx Degree is No Guarantee,” The Atlantic, available at h t t p : // w w w . t h e a t l a n t i c . c o m / e d u Miller, J. 1996. Search and Destroy: African c a t i o n / p r i n t / 2 0 1 4 / 0 5 / w h e n - a American Males and the U.S. Criminal Justice d e g r e e - i s - n o - g u a r a n t e e / 3 7 1 6 1 3 / System. New York: Cambridge University Press. Sharkey, P. (2013). Stuck in Place: Urban NeighborMoss, Philip and Tilly, Chris. 1996. “Soft Skills and Race: hoods and the End of Progress Toward Racial An Investigation of Black Men’s Employment Prob- Equality. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. lems.” Work and Occupations, Vol. 23, pp. 252-276. Taylor, Paul, et. al., 2010. Marrying Out: One-inNelson, A. A. & Gazley, B., 2014, “The Rise Seven New Marriages is Interracial or Interethnic. of School-Supporting Nonprofits,” Educa- PewResearch Center, A Social and Demographic tion Finance and Policy, Vol. 9, pp. 541-566. Trends Report, available at http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/files/2010/10/755-marrying-out.pdf Noguera, P. 1997. “Reconsidering the “Crisis” of the Black Male in America.” Social Justice, 24(2), 147-174. Theokas, C. & Saaris, R. 2013-June. Finding America’s Missing AP and IB Students. Pew Hispanic Center, 2013, A Nation of Immi- The Education Trust, Shattering Expectations grants. Pew Research Center, Retrieved from Series. Retrieved from http://www.edtrust.org/ Page 26 The Triple Whammy of Geographic Disadvantage sites/edtrust.org/f i les/M issing _ Students.pdf Weisner, Thomas S., editor, 2005. Discovering Successful Pathways in Children’s Development: Mixed Methos in the Study of Childhood and Family Life. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Wiltz, T. 2014, July 27. Expanding Age Gap between Whites and Minorities May Increase U.S. Racial Divide. America’s Wire. Retrieved from http://americaswire.org/drupal7/?q=content/ expa nd i ng -age-gap-bet ween-wh ites-a ndm i nor it ies-may-i ncrease-us-racia l- d iv ide Page 27