Document 12006568

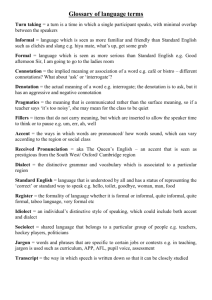

advertisement

FIELDNOTES Issue #8 25 February 2014 Last Wednesday, I attended the 3MT (i.e., “Three-­‐Minutes Thesis”) Competition, held in connection with Swansea Uni’s week of events honoring and celebrating the research this university sponsors. Each of twenty Swansea Uni doctoral students -­‐-­‐ most of them in STEM fields, a few in the social sciences, arts and humanities -­‐-­‐ took no more than exactly three minutes to present a summary of the research project he or she completed in order to earn the Ph.D. What in U.S. American universities is called a doctoral dissertation, in the U.K. is called a doctoral thesis. Whatever you call it, though, to boil yours down into a three-­‐minute sketch for listeners not in your field is difficult. No more than roughly half of the contestants hailed from Wales or elsewhere in the U.K. The others came from France, Iran, Pakistan, Thailand and a few other countries. Some entered the competition specifically with the intention of winning the cash prize. Others knew they had not yet developed the public speaking skills that would enable them to win, but decided they would challenge themselves, or practice talking about their research in preparation for participating in professional conferences. Australia’s University of Queensland initiated 3MT several years ago and the competition now has an international breadth. Winners of regional 3MT contests around the world may compete at national and international levels. Titles of scholarly research projects are notoriously long and ungainly. So the snappy 3MT condensations of what must be impenetrable titles amused me. One was “Watching Paint Burn,” about a chemical engineering project that examined how to make paint stay bright longer. Another was “My Neighbor is a Baboon,” a biology project investigating what the contact between baboon and chimpanzee communities can teach humans. The presenter showed two photographs: a young chimp and young baboon grooming one another; and then one of another chimp eating a baboon. Perhaps the title of the presentation should have been “Tastes Like Bonobo Monkey.” I spent a couple of days in London over the weekend. I have come through London a few times in recent years. My very first visit there occurred in 1974. At the time I stayed here for a number of weeks. Always an international city on the highest tier of impact and popularity, of course, London in those days had, in my opinion, a more distinctively British air than it seems to now. Many busy and prominent parts of today’s London could be exchanged for equivalent sections of Paris, New York or Berlin, for example, and—apart from distinctive architecture—no one could tell them apart. A J. Crew store is a J. Crew store, whether on Regent Street, the Champs Élysées, Fifth Avenue or the Kurfürstendamm. That said, London has a marked, unmistakable cosmopolitan atmosphere and electricity. I had a new food experience in London: aperas. These are Venezuelan sandwiches. You shape a gooey slab of cornmeal dough into a mound a bit bigger than a hamburger bun and throw it on the griddle for a few minutes. When it has browned on both sides, pull it open and fill with meat (chicken or beef), guacamole sauce, plantain, tomato and chopped lettuce, shredded cheese, and hot sauce. The sweet plaintain and the spicy sauces blend well, and the cornmeal bun, crisp on the outside, adds a roasty snap when you chew it. Messy but delicious and very filling. I had an odd experience in London: After a couple of days I found myself missing hearing the Welsh accent. (I had a similar experience over a decade ago when I spent a few days in Seattle at a conference: I began missing hearing the North Carolina voice.) I have read that in the U.K. and U.S.A. both, the impact of media planes down difference in regional inflection. More and more people in younger age cohorts are attempting to match their voices to the standardized or generic ones that they hear in the media. I have, however, concluded that regional accent gets more attention in the U.K. than it does in the U.S.A. It is not uncommon here, when someone refers to a friend or colleague from such-­‐and-­‐such a part of the U.K., to mention briefly in passing the extent of that person’s regional accent. During initial conversations with them, some Scottish or English instructors at Swansea Uni have said to me, only partly in jest, “I haven’t picked up the Welsh accent.” Several British people I have met have had over the years had one U.S. American or another say to them, “I just love your accent,” and speak of such encounters with bemusement, as if a “Yank” doing such a thing is a stock character. Yet on a number of occasions here, people have said to me, upon hearing me speak, “I love the accent.” In contrast, I don’t think I have ever said to anyone, “You should meet so-­‐and-­‐so, who by the way sounds like he never left Chicago” or “I’m from California and haven’t picked up the North Carolina accent.” (Several years ago at a professional conference, I struck up a conversation with an instructor from a Brooklyn community college. When I said I lived in North Carolina, she looked surprised and said, very earnestly, “You don’t sound like you’re from the south.” I guess the possibility of migration from one part of the U.S.A. to another escaped her.)