Document 12006565

advertisement

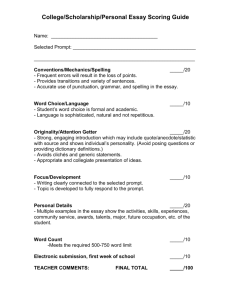

FIELDNOTES Issue #5 4 February 2014 Teaching started last week at Swansea University. I was initially a bit nervous because I didn’t know if the local students would respond to me. Each module (what in the U.S.A. we would call a course) consists of a 50-­‐minute lecture plus two 50-­‐ minute seminars, all of which typically are scheduled on different days of the week and different times of day. The difference between a lecture and a seminar is that a lecture is primarily the instructor doing the talking on the topic of the day. Seminars, in contrast, are class sessions during which the students perform a variety of learning tasks, and experience more interaction with the instructor. That first week, lecturing went well enough, and the seminars went especially well. I have already noticed some similarities and differences between the local students and my students at UNCW. They share, for example, a similar distaste for “early” classes. At a one o’clock seminar on Thursday, for example, one of the students, who had attended the nine a.m. lecture the day before, confessed, “This is a much better time for me than lecture. Nine in the morning is kind of early.” Early? Wait’ll you start “Workin’ for The Man,” my friend. I noticed, on the other hand, that the Swansea students contributed on Day One more readily than, in my experience, UNCW students seem to. After a few class meetings are behind us and I have conducted some exercises designed to encourage active participation, the UNCW students do contribute. But on the first days of class at UNCW, the students tend to say less rather than more. During the days leading up to the first week of classes, I struggled to write essay questions. Here an essay question is more what we in the U.S.A. might refer to as a writing prompt. My students here will each write two essays—what my U.S.A. students might call papers—about 3,000 words (a dozen pages or so) each, one due mid-­‐term, the other due at end of term. I sought to develop five prompts per essay, so that meant ten essay questions for a module. My students here will only be graded on the essays. The only other assessment option is an exam; and exams given here must be essay exams, written by hand during a prescribed time period. I didn’t want to read through a pile of handwritten exam papers, not even if it were one exam plus one essay. Each 3,000-­‐word essay must respond to one of the prompts I referred to, which must be made available to the students at the beginning of the semester. I worked closely with Dr. Farebrother, my mentor here, to revise my essay questions as straight-­‐to-­‐the-­‐point prompts. Here, for example, is one of my original prompts: Imagine that you are an officer in the U.S. Army in early 1946, several months after the September 1945 surrender of Japan. You receive the following order from your commanding officer: “You are to write a 3,000-word white paper summarizing key aspects of the performance of U.S. ground forces during the war. Specify at least two strengths U.S. ground troops tended to demonstrate during combat operations, and also specify at least two weaknesses.” (Assume that the audience for this white paper consists of government and military officials seeking a cogent, articulate sketch of the “good news” and “bad news” about how U.S. troops performed in combat.) Now, write the white paper described above. To gather necessary information, you may wish to consult memoirs by U.S. Army veterans, works by historians, autobiographies of military or government leaders, and critiques by allies as well as enemies. It turns out, though, that this prompt violates the preference for less rather than more content in a prompt, and the call for a prompt to elicit more analysis than description. So, given Dr. Farebrother’s feedback, here is how I ultimately revised the prompt: What are TWO strengths of U.S. American WWII ground troops and TWO weaknesses? Assess the impact of each strength and weakness on U.S. combat operations. Illustrate your answer with examples derived from memoirs, autobiographies, or critiques by allies or enemies. Last Saturday morning, I attended a workshop advertised in a promotional handbill I saw in the post office. The workshop, titled Contemplative Photography, taught attendees how to use photography as a contemplative practice, kind of like meditation. About ten participants met in a clubroom Singleton Park Botanical Gardens, a small venue with very pretty vegetation. Lee, the workshop facilitator, looked like a war photojournalist—short, wiry, dressed all in black and draped in camera gear. His black T-­‐shirt bore, in black-­‐and-­‐white, the cover image from the early-­‐‘60s record album Meet the Beatles. Most of us in the workshop were aged 40s through 60s. One attendee was a young Brazilian man studying engineering at Swansea University. Another was a British woman about my age who had married an American and lived in San Francisco for nearly two decades. They had just recently relocated to the UK. I mentioned that Los Angeles was my hometown. “L.A.,” she snorted. “The Bay Area rocks!” I checked her facial expression to see if she was perhaps being arch or ironic—but no, she was an actual Northern California exceptionalist, delighted to have a Southern Californian to abuse. Inwardly, I groaned, because I have, as a Californian, long been indifferent toward intrastate rivalry. It was fine when I attended summer camps where Northern California campers and I would insult one another; but I was a teenager then. So I simply replied, “Yes, the Bay Area is a great place, I visited there regularly for years but I haven’t been back since the mid-­‐‘90s.” Lee proposed that although sometimes technical concerns and inner dialogue is appropriate when taking photos, photography can at other times be the basis of a form of contemplative practice, which requires one to suppress the mind chatter. He suggested one become fully aware of what, within the boundaries marked by peripheral vision, one notices; reflect on what one notices; and, in his phrase that I particularly liked, “capture the equivalent” (i.e., capture an image that matches what you saw). Lee facilitated a number of exercises to enable us to practice these steps. The weather became very blustery about halfway through the workshop. Hail shot down for a while, the tiny pellets stinging my face thanks to a horizontal wind. However, I have often maintained that there is no such thing as bad weather, only the wrong clothing … and for the most part, I did have the right clothing, as did most of the attendees. So we could frolic in the botanical garden in order to the activities Lee tasked us with.