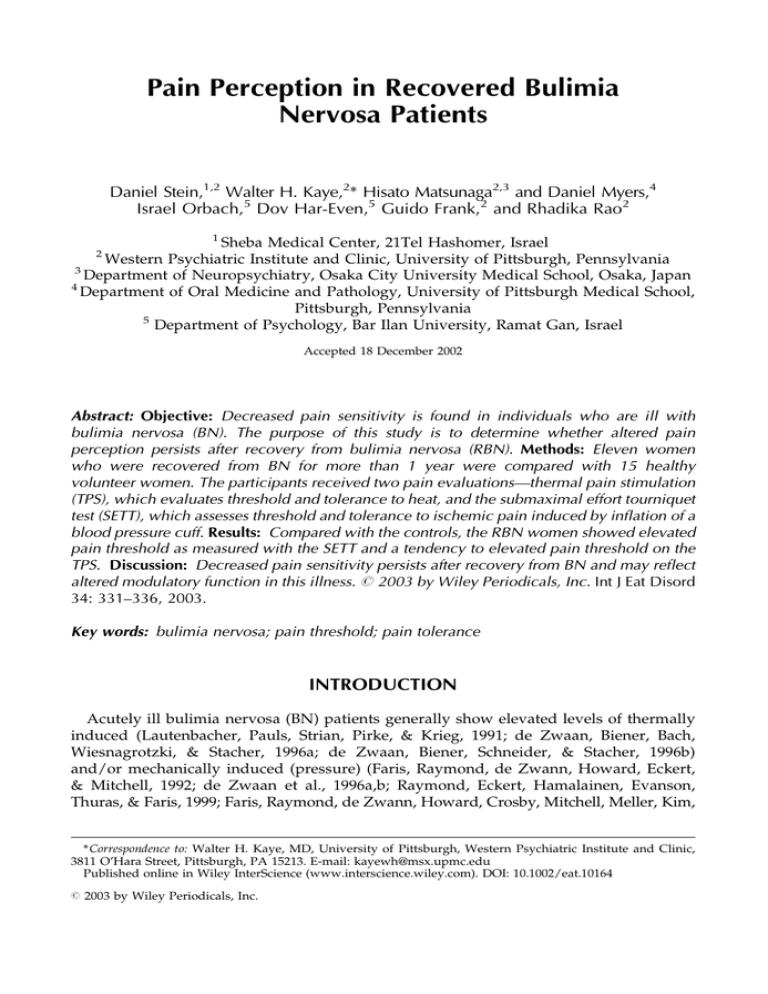

Pain Perception in Recovered Bulimia Nervosa Patients

advertisement

Pain Perception in Recovered Bulimia Nervosa Patients Daniel Stein,1,2 Walter H. Kaye,2* Hisato Matsunaga2,3 and Daniel Myers,4 Israel Orbach,5 Dov Har-Even,5 Guido Frank,2 and Rhadika Rao2 1 Sheba Medical Center, 21Tel Hashomer, Israel Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic, University of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 3 Department of Neuropsychiatry, Osaka City University Medical School, Osaka, Japan 4 Department of Oral Medicine and Pathology, University of Pittsburgh Medical School, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 5 Department of Psychology, Bar Ilan University, Ramat Gan, Israel 2 Accepted 18 December 2002 Abstract: Objective: Decreased pain sensitivity is found in individuals who are ill with bulimia nervosa (BN). The purpose of this study is to determine whether altered pain perception persists after recovery from bulimia nervosa (RBN). Methods: Eleven women who were recovered from BN for more than 1 year were compared with 15 healthy volunteer women. The participants received two pain evaluations—thermal pain stimulation (TPS), which evaluates threshold and tolerance to heat, and the submaximal effort tourniquet test (SETT), which assesses threshold and tolerance to ischemic pain induced by inflation of a blood pressure cuff. Results: Compared with the controls, the RBN women showed elevated pain threshold as measured with the SETT and a tendency to elevated pain threshold on the TPS. Discussion: Decreased pain sensitivity persists after recovery from BN and may reflect altered modulatory function in this illness. # 2003 by Wiley Periodicals, Inc. Int J Eat Disord 34: 331–336, 2003. Key words: bulimia nervosa; pain threshold; pain tolerance INTRODUCTION Acutely ill bulimia nervosa (BN) patients generally show elevated levels of thermally induced (Lautenbacher, Pauls, Strian, Pirke, & Krieg, 1991; de Zwaan, Biener, Bach, Wiesnagrotzki, & Stacher, 1996a; de Zwaan, Biener, Schneider, & Stacher, 1996b) and/or mechanically induced (pressure) (Faris, Raymond, de Zwann, Howard, Eckert, & Mitchell, 1992; de Zwaan et al., 1996a,b; Raymond, Eckert, Hamalainen, Evanson, Thuras, & Faris, 1999; Faris, Raymond, de Zwann, Howard, Crosby, Mitchell, Meller, Kim, *Correspondence to: Walter H. Kaye, MD, University of Pittsburgh, Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic, 3811 O’Hara Street, Pittsburgh, PA 15213. E-mail: kayewh@msx.upmc.edu Published online in Wiley InterScience (www.interscience.wiley.com). DOI: 10.1002/eat.10164 # 2003 by Wiley Periodicals, Inc. 332 Stein et al. Hartmen, & Eckert, in press) pain threshold and/or tolerance compared with controls. The mechanisms underlying these phenomena have yet to be determined. Recent data suggest that decreased pain sensitivity may be related to severity of bulimic symptoms (Faris et al., in press). Furthermore, pain detection threshold may increase during the interval between bingeing/purging episodes (Faris et al., 1998), and BN patients do not report greater pain unpleasantness compared with controls, despite showing significantly longer time before reaching pain tolerance (Girdler, Koo-Loeb, Pedersen, Brown, & Maixner, 1998). These findings raise the speculation that BN-related diminished pain sensitivity and pain unpleasantness may play a role in the maintenance of BN in minimizing the physical discomfort and increasing the self-reported calm and euphoria associated with the binge/purge cycle (Faris, Kim, Meller, Goodale, Hofbauer, Oakmon, Howard, Stevens, Eckert, & Hartmen, 1998; Girdler et al., 1998). Girdler and associates (1998) have additionally speculated that complex interactions between elevated opioid activity and vagal activity may be implicated in the hypoalgesia of BN. The aim of this study was to assess pain perception in women who were recovered from BN to determine whether decreased pain sensitivity is only a phenomenon related to pathological eating behavior or whether it persists after recovery. METHODS Patients Participants consisted of 11 recovered BN female patients (RBN) and 15 healthy matched volunteer women. All RBN patients had a previous lifetime DSM-IV (APA, 1994) diagnosis of BN and were required to have no history of AN. These participants also reported that in the past year they maintained a stable and normal weight (85% to 115% of average body weight [ABW]) (Metropolitan Life Tables, 1959); had not binged, purged (both vomiting and use of laxatives or diuretics), or engaged in restrictive eating patterns; and had regular menstrual cycles. RBN participants fulfilling all the inclusion but none of the following exclusion criteria were admitted to the study: (1) any axis I (DSM-IV, 1994) disorder in the past year. (2) Ever having a bipolar disorder (I and II), a schizophrenic spectrum disorder, organic brain syndrome, and dementia. The RBN patients had, in addition, no evidence of present or past medical illness, neurological illness, or chronic pain condition; had not used psychoactive medications in the past year; and had no current or regular use of analgesics or of any other medications. These patients were previously treated in the eating disorders treatment program at the Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Healthy volunteers consisted of 15 age-matched women whose weight has been between 90% and 115% of ABW since menarche. These volunteers had no lifetime or present psychiatric, medical, or neurological illness; no chronic pain condition; no regular use of analgesics or any other medications; and no stigmata suggestive of an eating disorder (ED). These volunteers came from the staff of the Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. All RBN patients and healthy controls were Caucasian. To control for menstrual variations in pain sensitivity (Lautenbacher, Pauls, Strian, Pirke, & Krieg, 1990), all RBN and control participants were studied during the first 14 days (follicular phase) of their menstrual cycle. ABW for each participant was assessed Pain Perception 333 with the Metropolitan Life Tables (1959), and body mass index was calculated as kilograms divided by height in meters squared. All participants gave informed consent to participate in the study, which was approved by the center’s institutional review board and were paid for participating in the study. Instruments Measurement of Pain Perception Thermal Pain Stimulator (TPS). This instrument is modeled after Procacci (1979). In the first stage, a 1.5-cm radius area was colored in black ink on the participant’s wrist. A 75-watt bulb was then held 7 cm from the wrist. Pain threshold was defined as the total time measured (with a stopwatch) from onset of illumination until the participant reported feeling pain, and pain tolerance was the total time measured from onset of illumination until the participant withdrew her wrist. To ensure thermal levels, the bulb was illuminated for 5 minutes before use with each participant. The procedure was stopped after 8 minutes according to the requirements of previous studies. It was repeatedly shown to be a valid and reliable pain measure (Procacci, 1979; Orbach, Palgi, Stein, Har-Even, Loten-Pelag, Asterov, & Elizar, 1996). Submaximal Effort Tourniquet Test (SETT). This technique has been extensively used in the study of experimental pain in humans (Moore, Duncan, Scott, Gregg, & Ghia, 1978), as well as in a previous study of ill BN patients (Girdler et al., 1998). The first step was raising the arm for 10 seconds and temporary application of a tight bandage to drain residual blood. Ischemia of the forearm was achieved by inflation of a blood pressure cuff to 250 mmHg. Maximum handgrip was determined immediately before ischemia by use of a handgrip dynamometer. The participant was instructed to squeeze the dynamometer with as much force as possible. Once ischemia was produced, participants squeezed the dynamometer 20 times at 30% maximal grip force. Each squeeze was for 2 seconds, with an intergrip interval of 2 seconds. The onset, duration, and magnitude of each handgrip were signaled by computer-controlled signals. After the 20 grips were completed, participants were asked to report the time they started to feel any pain (pain threshold, measured with a stopwatch from the onset of cuff inflation) and the time the pain becomes intolerable (pain tolerance) (Maixner Fillingim, Booker, & Sigurdson, 1995). The cuff was deflated at that time or after 25 minutes, whichever came first, to guarantee the participants’ safety (Maixner et al., 1995). Psychiatric diagnosis was assessed with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders-Patient Edition (SCID-I/P, Version 2.0) (First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 1995). Recovery from past BN, or not ever having an ED in the controls, was assessed with the Eating Disorders Family History Interview (EDFHI) (Strober, 1987). Procedure A screening interview was first conducted by a psychiatrist (DS). If the participant was screened positively, she received the SCID-I/P, Version 2.0, the EDFHI, and a thorough evaluation of medical and neurological condition, including measurement of weight and height. If the participant fulfilled all inclusion and exclusion criteria, she was accepted into the protocol. All participants were then admitted for 1 day to the Eating Disorders Research Laboratory of the Center for Overcoming Problem Eating, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and participated in an identical study design. The participants were seated in a comfortable chair, and all evaluations took place in the supine position. TPS was administered first 334 Stein et al. and the SETT 60 minutes after completing the TPS. The two brain hemispheres handle pain differently, and the maximal handgrip used in the SETT is expected to be different in the dominant compared with the nondominant hand. Therefore, we assigned the participants randomly to be tested with either the TPS or the SETT in their dominant hand. To control for circadian variations in pain response (Moore et al., 1978), we performed all evaluations between 12:00 to 16:00. Evaluators were trained in the use of the TPS and SETT and were blind to the diagnosis of the participants. Statistical Analysis Two-tailed t tests and chi-square tests were used for the between-group comparison of the demographic and clinical parameters and the TPS and SETT pain threshold. Pain tolerance cannot be reached until pain is detected, namely, within an individual it is dependent on the pain threshold score. We therefore used an analysis of covariance with pain threshold as a covariate (ANCOVA) to assess the between-group differences in pain tolerance. All results are described as mean SD. RESULTS The mean age of the RBN participants was 28.8 5.5 years and of the controls 25.1 4.8 years (t[df ¼ 24] ¼ 1.80; NS). The mean ABWs for the RBN participants and controls were 107.8% 12.1% and 104.6% 10.6%, respectively (t[24] ¼ 0.70; NS), and the mean body mass indexes were 22.4 2.5 and 21.7 2.3 kg/m2, respectively (t[24] ¼ 0.76; NS). The RBN women were recovered for a mean period of 5.5 years (range, 1–12 years). In terms of the TPS test, the pain threshold for 7 of the 11 RBN patients and 3 of the 15 controls was more than 8 minutes, defined as the time limit for stopping the experiment. This precluded any meaningful analyses concerning TPS pain tolerance. Nevertheless, a significantly greater percentage of the RBN patients had TPS pain threshold of more than 8 minutes compared with the controls (2[df ¼ 1] ¼ 4.03; p < 0.04). For the SETT, we found that pain threshold was 3.10 2.7 minutes for the RBN patients and 1.15 1.6 minutes for the controls (t[df ¼ 24] ¼ 2.08; p < 0.05). Although a significant difference was also shown for pain tolerance between the RBN (8.88 5.3 minutes) and control participants (3.63 3.5 minutes) (t[df ¼ 24] ¼ 2.20; p < 0.04), this difference failed to retain its significance when using ANCOVA with pain threshold as a covariate (F[1,21] ¼ 0.04; NS). The evaluation of the TPS and SETT in either the dominant or nondominant hand had no significant influence on any of the pain measures. DISCUSSION To our knowledge, this is the first study showing that elevated pain threshold persists after recovery from BN. The persistence of decreased pain sensitivity after recovery raises the possibility that it is a trait associated with the pathophysiology of BN, although it is possible that it is a consequence of this disorder. Recent findings in acutely ill BN patients suggest a putative role of pain in the maintenance of BN. That is, bingeing and purging may be a means of temporary normalization of elevated pain threshold (Faris et al., 1998). Perhaps pain threshold reflects exaggerated modulation of other phenomena such as Pain Perception 335 mood states, which binge and purge behaviors may also temporarily blunt (Steinberg, Tobin, & Johnson, 1990). The etiology underlying persistent decreased pain sensitivity after recovery from BN has yet to be determined. Recent studies raise the possibility that altered central serotonergic activity may persist after recovery from BN (Kaye, Greeno, Moss, Fernstrom, Lilenfeld, Waltzin, & Mann, 1998). Decreased pain sensitivity after recovery may also be related to altered serotonin activity. In this respect, drugs that act on serotonin systems are known to have effects on pain sensitivity (e.g., Schreiber, Stein, & Floman, 1996). Our study has several limitations. The sample size is relatively small. This precludes the assessment of a possible confounding effect of the order of administration of the pain measurements. The TPS may be considered less accurate than currently used computercontrolled pain measure devices (Lautenbacher et al., 1990). The requirement to stop this procedure after 8 minutes precludes meaningful analyses of TPS pain threshold and tolerance. Nevertheless, the finding that the TPS pain threshold of most RBN patients is more than 8 minutes compared with only a few of the controls may be of relevance, because it is consistent with the results of the SETT. Our results need to be interpreted with caution, because techniques used for the determination of pain thresholds at which stimuli of different nature are perceived as painful are prone to yield results influenced by factors not necessarily related to pain perception (de Zwaan et al., 1996b). The advantages of our study include the careful selection of the RBN patients and controls and the exclusion of participants having other DSM-IV axis I diagnoses that may affect pain perception (e.g., affective disorders or substance use) (Lautenbacher & Krieg, 1994). In addition, ischemic pain generated with the SETT is considered an experimental pain-induction method that particularly mimics pain sensations similar to those experienced in the natural environment (Moore et al., 1978). In conclusion, this study is the first to suggest that pain threshold may be elevated not only in acutely ill but also in recovered BN patients. Further studies in larger groups of RBN patients assessing the association of decreased pain sensitivity with elevated vagal, opioid, and/or serotonergic activity, as well as with psychological correlates that persist after recovery, are required to establish the importance of pain perception in the pathophysiology of BN. REFERENCES American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (3rd ed.), Washington, DC: Author. de Zwaan, M., Biener, D., Bach, M., Wiesnagrotzki, S., & Stacher, G. (1996a). Pain sensitivity, alexithymia, and depression in patients with eating disorders: are they related? Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 41, 65–70. de Zwaan, M., Biener, D., Schneider, C., & Stacher, G. (1996b). Relationship between thresholds to thermally and to mechanically induced pain in patients with eating disorders and healthy controls. Pain, 67, 511–512. Faris, P.L., Raymond, N.C., de Zwaan, M., Howard, L.A., Eckert, E.D., & Mitchell, J.E. (1992). Nociceptive, but not tactile, thresholds are elevated in bulimia nervosa. Biological Psychiatry, 32, 462–466. Faris, P.L., Kim, S.W., Meller, W.H., Goodale, R.L., Hofbauer, R.D., Oakman, S.A., Howard, L., Stevens, E.R., Eckert, E.D., & Hartman, B.K. (1998). Effects of ondansteron, a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist, on the dynamic association between bulimic behaviors and pain thresholds. Pain, 77, 297–303. Faris, P.L., Raymond, N.C., de Zwaan, M., Howard, L.A., Crosby, R.D., Mitchell, J.E., Meller, W.H., Kim, S.W., Hartman, B.K., & Eckert, E.D. (in press). Elevated pain thresholds in bulimia nervosa: relationship to disease symptoms. Physiology and Behavior. First, M.B., Spitzer, R.L., Gibbon, M., & Williams, J.B.W. (1995). Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders—Patient Edition (SCID-I/P, Version 2.0). New York: Biometrics Research Institute, New York State Psychiatric Institute. 336 Stein et al. Girdler, S.S., Koo-Loeb, J., Pedersen, C.A., Brown, H.J., & Maixner, W. (1998). Blood pressure-related hypoalgesia in bulimia nervosa. Psychosomatic Medicine, 60, 736–743. Kaye, W.H., Greeno, C.G., Moss, H., Fernstrom, J., Fernstrom, M., Lilenfeld, L.R., Weltzin, T.E., & Mann, J.J. (1998). Alterations in serotonin activity and psychiatric symptomatology after recovery from bulimia nervosa. Archives of General Psychiatry, 55, 927–935. Lautenbacher, S., Pauls, A.M., Strian, F., Pirke, K.M., & Krieg, J.C. (1990). Pain perception in patients with eating disorders. Psychosomatic Medicine, 52, 673–682. Lautenbacher, S., Pauls, A.M., Strian, F., Pirke, K.M., & Krieg, J.C. (1991). Pain sensitivity in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. Biological Psychiatry, 29, 1073–1078. Lautenbacher, S., & Krieg, J.C. (1994). Pain perception in psychiatric disorders: a review of the literature. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 28, 109–122. Maixner, W., Fillingim, R, Booker, D., & Sigurdson, A. (1995). Sensitivity of patients with painful temporomandibular disorders to experimentally evoked pain. Pain, 63, 341–351. Metropolitan Life Insurance Company. (1959). New weight standards for men and women. Statistical Bulletin, 40, 1–11. Moore, P.A., Duncan, G.H., Scott, D.S., Gregg, J.M., & Ghia, J.N. (1978). The submaximal effort tourniquet test: its use in evaluating experimental and chronic pain. Pain, 6, 375–382. Orbach, I., Palgi, Y., Stein, D., Har-Even, D., Lotem-Peleg, M., Asherov, J., & Elizur, A. (1996). Tolerance for physical pain in suicidal patients. Death Studies, 20, 327–341. Procacci, P. (1979). Methods for the study of pain threshold in man. In J.J. Bonica, J.C. Leibskind, & D.G. AlbeFessard (Eds.), Advances in pain research and therapy (vol. 3) (pp. 781–790). New York: Raven Press. Raymond, N.C., Eckert, E.D., Hamalainen, M., Evanson, D., Thuras, P.D., & Faris, P.L. (1999). A preliminary report on pain thresholds in bulimia nervosa during a bulimic episode. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 40, 229–233. Schreiber, S., Stein, D., & Floman, Y. (1996). Psychologic approaches to the treatment of chronic low back pain. In S.W. Wiesel, J.N. Weinstein, H. Herkowitz, J. Dvorak, & G. Bell (Eds.), The lumbar spine (2nd ed.) (pp. 1018–1041). Philadelphia: WB Saunders Co. Steinberg, S., Tobin, D., & Johnson, C. (1990). The role of bulimic behaviors in affect regulation: different functions for different patient subgroups? International Journal of Eating Disorders, 9, 51–55. Strober, M. (1987). The Eating Disorders Family History Interview. Los Angeles: University of California.