An Introduction to Mentoring Principles, Processes, and Strategies for Facilitating

advertisement

An Introduction to Mentoring Principles, Processes, and Strategies for Facilitating

Mentoring Relationships at a Distance

A.T. Wong

K. Premkumar

Introduction

This digital learning object was developed for use primarily by faculty and students in the

context of higher education, but it may also be a useful resource for individuals in professional

organizations.

Mentoring is a learning process where helpful, personal, and reciprocal relationships are built

while focusing on achievement; emotional support is a key element. Within mentoring

relationships, mentees develop and learn through conversations with more experienced mentors

who share knowledge and skills that can be incorporated into their thinking and practice. By

comparison, tutoring or coaching is provision of academic and professional assistance in a

particular area with a sole focus on competence.

The process of mentoring may be viewed under three models – the apprentice, competency and

reflective models. In the apprentice model, the mentee observes the mentor and learns. In the

competency model, the mentor gives the mentee systematic feedback about performance and

progress. In the reflective model, the mentor helps the mentee become a reflective practitioner.

This learning object subscribes to the reflective model in which mentoring is seen as an

intentional, nurturing and insightful process that provides a powerful growth experience for both

the mentor and mentee. You will be introduced to a mentoring relationship process that develops

through four stages – preparing, negotiating, enabling and reaching closure.

Mentoring relationships can be formal or informal. Formal mentor relationships are usually

organized in the workplace where an organization matches mentors to mentees for developing

careers. Informal mentor relationships usually occur spontaneously and are largely

psychosocial; they help to enhance the mentee’s self esteem and confidence by providing

emotional support and discovery of common interests.

Technology is increasingly used in the mentoring process because of its widespread accessibility

and potential to overcome the barriers of time and geographical location between mentors and

mentees. This learning object will introduce you to a number of benefits of technology-mediated

mentoring as well as specific challenges that have yet to be resolved. You will also be introduced

to selected strategies that would enhance communication and understanding when mentoring

relationships occur at a distance.

Copyright © A. T. Wong & K. Premkumar 2007. Source: An Introduction to Mentoring Principles, Processes and Strategies for

Facilitating Mentoring Relationships at a Distance. http://www.usask.ca/gmcte/drupal/?q=resources

Contact angie.wong@usask.ca or kalyani.premkumar@usask.ca.

It is important to realize, however, that the purposes and goals of mentoring programs and the

human nature of mentoring relationships must drive the mentoring process, rather than the

advantages provided by technology.

Goals

This learning object has five goals:

1. Introduce mentoring as a learning relationship that is rooted in principles of adult

learning.

2. Identify the key tasks and processes for enhancing the mentoring relationship.

3. Provide examples of process tools and strategies for understanding and operationalizing

the mentoring relationship.

4. Identify the special challenges and opportunities that may occur when mentoring is

conducted in a distance-learning context.

5. Introduce some technology-mediated strategies that could help to bridge the gap when

mentor and mentee are at a distance from each other.

Copyright © A. T. Wong & K. Premkumar 2007. Source: An Introduction to Mentoring Principles, Processes and Strategies for

Facilitating Mentoring Relationships at a Distance. http://www.usask.ca/gmcte/drupal/?q=resources

Contact angie.wong@usask.ca or kalyani.premkumar@usask.ca.

PART ONE

Introduction

History has shown us that human beings, like trees in an old forest, tend to thrive best when they

grow in the presence of those who have gone before them. In Greek mythology, Athena, the

goddess of wisdom, assumed the form of Mentor to look after and guide Telemachus, son of

Odysseus, who had left home to fight in the Trojan war. The account of Mentor in The Odyssey

points to several conclusions about the activity which bears Mentor’s name (Anderson &

Shannon, 1982). First, mentoring is an intentional process. Second, mentoring is a nurturing

process that fosters the development of the protégé towards his full potential. Third, mentoring is

an insightful process in which the wisdom of the mentor is acquired and applied by the

beneficiary.

In contemporary times, mentors have played a vital role in the development of individuals in

education and business organizations. Mentoring for a professional career became a topic of

research in the mid-1970s. Caffarella (1992) defined mentoring as an “intense caring relationship

in which persons with more experience work with less experienced persons to promote both

professional and personal development” (p. 38). Daloz (1986) was more expressive in his

description of mentors as guides who “lead us along the journey of our lives … they cast light on

the way ahead, interpret arcane signs, warn us of lurking dangers, and point out unexpected

delights along the way” (p. 17).

The beneficiary of the process is often referred to as the mentee, but various writers have

pointed out that the mentoring relationship could be a development opportunity for both mentors

and mentees (Daloz, 1996, 1999; Albom, 1997; Hansman, 2002). Mentoring relationships have a

potential to facilitate psychosocial development – mentored individuals enjoy higher selfconfidence, self-efficacy, and self-assurance. Mentors too can benefit from enhanced selfconfidence of their capabilities for reflective thinking and communication, as well as personal

satisfaction of contributing to the discipline and the next generation.

Mentoring may be especially important to first-generation university students, first-generation

professionals, and those entering fields dominated by persons of a different gender or race

(Stalker, 1996; Ragins, 1997; Gordon and Whelan, 1998). In higher education, Lyons, Scroggins,

and Rule (1990) found that mentors not only transmitted formal academic knowledge and

provided socialization experiences into their chosen discipline, but also bolstered the students’

confidence and professional identity, giving them a vision of the identity they might one day

achieve.

Here we focus on mentoring relationships for academic development. This learning object

provides the background information required for starting a mentoring program. It will be most

beneficial to those who have always wanted to start a mentoring program but did not know how.

This information will also be useful to those who are contemplating the introduction of

technology to supplement their mentoring program.

Copyright © A. T. Wong & K. Premkumar 2007. Source: An Introduction to Mentoring Principles, Processes and Strategies for

Facilitating Mentoring Relationships at a Distance. http://www.usask.ca/gmcte/drupal/?q=resources

Contact angie.wong@usask.ca or kalyani.premkumar@usask.ca.

Principles of adult learning underlying the mentoring relationship

Almost a century ago, Dewey (1916) emphasized the importance of the individual experience in

the learning process and the value of interaction in creating a positive learning environment.

Later learning theorists such as Lewin (1951), Piaget (1969), and Vygotsky (1981) extended

Dewey’s ideas. Lewin conceptualized learning as deriving from here-and-now concrete

experiences coupled with feedback loops. Piaget contended that learning involves

accommodating concepts to experience and assimilating experience into concepts. Vygotsky

introduced the concept of the “zone of proximal development,” which refers to the difference

between an individual solving a problem independently and solving a problem together with a

peer who is more advanced in knowledge or skills.

Knowles (1980) coined the term andragogy to refer to the facilitation of learning among adults.

The current focus of mentoring as a process-oriented relationship that involves knowledge

acquisition and reflective practice is consistent with the principles of adult learning promoted by

Knowles:

•

•

•

•

•

•

Adults have a need to be self-directing.

Adults learn best when they are involved in planning, implementing and evaluating their

own learning.

Adult learners are motivated by an immediacy of application.

An individual’s life experiences are primary learning resources.

Interactions with other individuals enrich the learning process.

The role of the facilitator is to promote and support conditions necessary for learning to

take place.

Based on these principles of adult learning, three assumptions can be made about the nature of

mentoring:

1. Mentoring can be a powerful growth experience for both the mentor and the mentee.

2. Mentoring is a process of engagement that is most successful when done collaboratively.

3. Mentoring is a reflective process that requires preparation and dedication.

Four phases in the mentoring relationship

Mentoring relationships progress through predictable phases that build on one another to form a

developmental sequence. Zachary (2000) named four phases and applied an agricultural analogy

in demonstrating how the phases can be connected:

•

Preparing – This initial phase can be compared to tilling the soil before planting and can

involve a number of processes such as fertilizing, aerating, and ploughing the soil.

Copyright © A. T. Wong & K. Premkumar 2007. Source: An Introduction to Mentoring Principles, Processes and Strategies for

Facilitating Mentoring Relationships at a Distance. http://www.usask.ca/gmcte/drupal/?q=resources

Contact angie.wong@usask.ca or kalyani.premkumar@usask.ca.

Potential mentors similarly go through a variety of processes to assess their own

motivations and readiness for the prospective mentoring relationship.

•

Negotiating – Successfully completing the negotiating phase is like planting seeds in

well-cultivated soil. There is a greater probability of fruition of the mentoring

relationship.

•

Enabling – This phase can be likened to nurturing growth as the seeds take root. It takes

longer to complete than the other phases, as it is the implementation phase of the

relationship.

•

Coming to closure – Zachary compared this phase to reaping the harvest. Regardless of

whether the mentoring relationship has been positive or not, this phase offers opportunity

for the mentoring partners to harvest their learning and move on.

Understanding of the phases is key in successful mentoring relationships, including awareness

that there may be overlaps between the phases. For example, during the enabling phase, one

mentoring partner may move geographically to another location and thereby trigger a need to

renegotiate the mentoring agreement or to experiment with technology-mediated tools to support

the relationship.

In the following sections, each of the four phases will be described in greater detail and some

process tools and strategies will be introduced.

Preparing for the mentoring relationship

Individuals who have never played the role of mentor may assume that having subject expertise

and experience would be adequate preparation for being a mentor. Zachary (2000) contended

that mentors who assume the mentor role without preparing themselves are often disappointed

and dissatisfied. She advised potential mentors to reflect on their motivation for engaging in a

mentoring relationship and to assess their own readiness for the mentoring relationship.

Motivation has an impact on the sustainability of a relationship. Mentors also need to be

comfortable using a range of process skills. Refer to the motivation and readiness selfassessment checklists in the appendix section.

The mentoring relationship that is advocated in this learning object is one that shifts the mentor’s

role from “sage on the stage” to the “guide on the side.” The model of a mentor “for all seasons

and all reasons” is an unrealistic expectation, and is a major reason why many qualified potential

mentors shy away from the mentor role.

Instead of the mentor taking full responsibility for the mentee’s learning, the mentee should learn

to set learning priorities and become increasingly self-directed. If the mentee is not ready to

assume this degree of responsibility, the mentor nurtures the mentee’s capacity for self-direction

Copyright © A. T. Wong & K. Premkumar 2007. Source: An Introduction to Mentoring Principles, Processes and Strategies for

Facilitating Mentoring Relationships at a Distance. http://www.usask.ca/gmcte/drupal/?q=resources

Contact angie.wong@usask.ca or kalyani.premkumar@usask.ca.

over the course of the relationship. Given the growing need for lifelong learning in all sectors of

work and community life, it may be more desirable for an individual to have multiple mentors

over a lifetime, and perhaps even multiple mentors at the same time.

In order to build a solid foundation for an effective mentoring relationship, mentors should have

a clear understanding of their own personal journeys. In Composing a Life (1989), Bateson

reminds us “the past empowers the present, and the groping footsteps leading to the present mark

the pathways to the future” (p. 34). Zachary (2000) developed an exercise to help potential

mentors reflect on their own journeys of learning as a prelude to understanding the mentee’s

needs and aspirations. Refer to the Mentor Journey Time Line in the appendix for a set of

questions that will trigger self-reflection.

Zachary suggested a second set of questions to help potential mentors prepare themselves for

understanding the individuals they may be mentoring. The questions are also useful for testing

assumptions if the mentor already knows something about the mentee.

Brookfield (1986) contended that an important element in facilitating adult learning is helping

learners become aware of their own idiosyncratic learning styles. Learning styles refers to the

pattern of preferred responses an individual uses in a learning situation. Brookfield contends that

an important element in facilitating adult learning is helping learners become aware of their own

idiosyncratic learning styles. Dialogue between the mentoring partners at the negotiation phase

will assist the mentor in knowing when to step forward and when to hold back, and to respect

different styles that may have a positive impact on the mentoring relationship.

Copyright © A. T. Wong & K. Premkumar 2007. Source: An Introduction to Mentoring Principles, Processes and Strategies for

Facilitating Mentoring Relationships at a Distance. http://www.usask.ca/gmcte/drupal/?q=resources

Contact angie.wong@usask.ca or kalyani.premkumar@usask.ca.

Negotiating the mentoring relationship

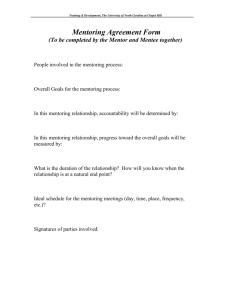

Negotiating is the phase when the mentoring partners come to agreement on learning goals and

define the content and process of the relationship. It usually begins with a free-flowing

conversation that takes place over one or more occasions and results in a shared understanding of

the desired outcomes and delineation of responsibilities. At the end of this phase, the mentoring

partners should ideally have collaboratively explored:

•

•

•

•

•

•

Desired learning outcomes

Criteria for measuring success

Mutual responsibilities

Accountability assurances

Protocols for addressing problems

An action plan for achieving the learning goal

Refer to the appendix for a list questions: “Negotiating Outcomes and Processes” that you could

pose to the mentee in your initial conversation. They will assist you in negotiating the process

and the desired learning outcomes for the mentee.

One strategy used to support diversity in styles and to promote accountability is to have the

mentee summarize the mentoring session at the close of each interaction and record what has

been learned or request clarification on specific issues. These notes are reviewed by the mentee

at the beginning of the next session and can be used as a trigger for conversation. Mentors can

also make progress notes throughout the mentoring relationship.

One of the most important outcomes of the negotiating phase is boundary setting by both the

mentor and the mentee. From the mentor’s perspective, boundary has to do with expectations of

access and time. For example: Does being a mentor mean the mentee has unlimited access to you

for the duration of the relationship? What is the limit? Both mentoring partners need to decide on

when and where to meet, what the agenda will be for the meeting, and establish a mechanism to

indicate a topic has been sufficiently explored.

Enabling the mentoring relationship

Anderson and Shannon (1988) believed that good mentors should be committed to three values.

First, mentors should be disposed to opening themselves to their mentees – for example, allow

their mentees to observe them in action and convey to them the reasons behind their decisions

and actions. Second, mentors should be prepared to lead their mentees incrementally over time.

Third, mentors should be willing to express care and concern about the personal and professional

welfare of their mentees.

Copyright © A. T. Wong & K. Premkumar 2007. Source: An Introduction to Mentoring Principles, Processes and Strategies for

Facilitating Mentoring Relationships at a Distance. http://www.usask.ca/gmcte/drupal/?q=resources

Contact angie.wong@usask.ca or kalyani.premkumar@usask.ca.

Zachary (2000) pointed out that mentors, in addition to their expertise and experience, need to be

familiar with specific process skills that can facilitate the mentoring process. The following

strategies could be particularly useful:

1. Asking questions that will help mentees to reflect on and articulate their own thinking,

for example

• Could you tell me a bit more about what you mean by…?

• It sounds as if this is the tip of the iceberg. Let’s think about this some more and

discuss it at our next conversation.

• That’s an interesting way of describing the problem. How would you apply that to

individuals of a different gender?

2. Reformulating statements help mentors to clarify their own understanding and encourage

mentees to reflect on what they articulated, for example

• I think what I heard you saying was …

• My understanding is…

3. Summarizing helps to remind the mentoring partners of what has transpired and allows

both parties to check out assumptions in the process, for example

• As a result, I feel we have achieved…

• We’ve spent our time this morning… but I gather you feel you’d rather…

4. Listening for silence – Silence can indicate boredom, confusion, discomfort or

embarrassment. On the other hand, some individuals just need time out to think quietly.

5. Providing feedback that is authentic and suggests future action, for example

• I like the way you… next time you might try…

• You made a really good start with… what I’d like to see is…

Because of their experience and accumulated insights, mentors can guide a mentee’s sense of the

possible. Modeling behavior and sharing stories help to inspire and inform the mentee. By

fostering reflective practice, the mentor helps the mentee to take a long view and create a vision

of what might be. Reflective practice should be encouraged during and after the mentoring

relationship.

Shon’s (1983) reflection-in-action model illuminates the expertise that knowledgeable

practitioners reveal in their spontaneous, skillful execution of a publicly observable performance.

The experts often have difficulty in making the performance verbally explicit; they

characteristically know more than they can say. Polyani (1967) coined the term tacit knowledge

to describe this type of knowledge. Mentors can model reflection-in-action by pausing and

verbalizing their thoughts about what they have done in order to discover how an action may

have contributed to both intended and unintended outcomes.

Copyright © A. T. Wong & K. Premkumar 2007. Source: An Introduction to Mentoring Principles, Processes and Strategies for

Facilitating Mentoring Relationships at a Distance. http://www.usask.ca/gmcte/drupal/?q=resources

Contact angie.wong@usask.ca or kalyani.premkumar@usask.ca.

Practitioners of a particular profession differ from one another in terms of their personal

experiences and styles of operation, but they also tend to share a common body of explicit

knowledge, a more or less systematically organized set of values, procedures, and norms in

terms of which they make sense of practice situations. This explicit knowledge constitutes an

acceptable professional conduct that mentors can share with their mentees. During the enabling

phase of the mentoring relationship, mentees are gradually initiated into the traditions of a

community of practitioners. They learn their conventions, languages, constraints, repertoire of

exemplars, and patterns of knowing-in-action.

Coming to closure in the mentoring relationship

When mentors and mentees are involved in a formal mentoring program, there is usually an

externally structured timeline for the mentoring relationship to come to an end. In informal

mentoring relationships, it is helpful for the partners to agree at the beginning on the process for

coming to closure.

The process of coming to closure can be situated around a focused conversation about the

specific learning that had taken place during and as a result of the mentoring relationship.

Murray (1999) pointed out that a constructive conversation is a blameless, no-fault, reflective

conversation about both the process and content of the learning. Both mentors and mentees share

what each had learned and how they might apply and leverage that knowledge in the future.

Zachary (2000) suggested that even when a mentoring relationship has become beset with

problems, reaching a learning-focused conclusion can turn the whole experience into a positive

one. The mentor could initiate a conversation with the following approaches:

•

•

•

Acknowledge the difficulty without casting blame – for example, “It looks as though

we’ve come to an impasse …”

Consider what went right with the relationship as well as what went wrong – for example,

“Let’s look at the pluses and minuses of our relationship so that we can each learn

something from the process we have undergone.”

Express appreciation – for example, “Although we haven’t been able to achieve all of

your objectives, I think we were successful in one area. I attribute this success to your

persistence and determination, characteristics which will be very helpful in your new

job.”

Copyright © A. T. Wong & K. Premkumar 2007. Source: An Introduction to Mentoring Principles, Processes and Strategies for

Facilitating Mentoring Relationships at a Distance. http://www.usask.ca/gmcte/drupal/?q=resources

Contact angie.wong@usask.ca or kalyani.premkumar@usask.ca.

Zachary (2000) further advised that it is important to celebrate the conclusion of a successful

mentoring relationship. Mentors could acknowledge and celebrate the mentee’s successful

journey via both verbal and written expressions of appreciation. Verbal comments should be

specific and focused on behaviours, for example:

•

•

•

“I admire …”

“You have a real knack for …”

“I especially appreciated it when you …”

Written notes from the mentor could offer a permanent record of support and encouragement as

well as a memento. For example, the note could focus on:

•

•

•

What you learned from your mentee

An incident that has special meaning for you

A motivational message for the future

Closure links the present to the future for both mentors and mentees.

Copyright © A. T. Wong & K. Premkumar 2007. Source: An Introduction to Mentoring Principles, Processes and Strategies for

Facilitating Mentoring Relationships at a Distance. http://www.usask.ca/gmcte/drupal/?q=resources

Contact angie.wong@usask.ca or kalyani.premkumar@usask.ca.

Appendix

Mentor Motivation Checklist

Some reasons why mentoring may appeal to an individual:

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

I like the feeling of having others seek me out for advice or guidance.

I find that helping others is personally satisfying.

I have a particular area of expertise that I want to pass on to others.

I enjoy collaborative learning; a mentoring relationship could be an opportunity for this

to happen.

I find working with others who are different from me to be energizing.

I feel it is my responsibility to help our staff become better contributors to our

organization.

Other people have made it possible for me to be where I am today; I feel I should do the

same to help others accelerate their career development.

I look for opportunities to further my own growth.

Mentor Readiness Checklist

The following generic process skills for mentors are modified from Zachary (2000).

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

Brokering relationships – laying the groundwork for mentees to connect with other

people who can be resources for them.

Coaching – helping mentees to fill particular knowledge or skill gaps by modeling the

behaviors.

Communicating –includes listening effectively, checking for understanding, articulating

clearly, picking up on non-verbal clues.

Encouraging – pushing at the right time and in an appropriate manner to inspire or

motivate.

Facilitating – establishing a friendly and respectful climate for learning; involving the

mentees in planning and evaluating the learning.

Goal-setting – assisting mentees in clarifying and setting realistic goals.

Managing conflict – engaging the mentees in the solution of a problem, not solving the

problem for them.

Reflecting – modeling the process of articulating and assessing learning and considering

the implication of that learning for future action.

Copyright © A. T. Wong & K. Premkumar 2007. Source: An Introduction to Mentoring Principles, Processes and Strategies for

Facilitating Mentoring Relationships at a Distance. http://www.usask.ca/gmcte/drupal/?q=resources

Contact angie.wong@usask.ca or kalyani.premkumar@usask.ca.

Mentor Journey Time Line

The following exercise for mentors is modified from Zachary (2000).

This exercise is intended to help you reflect on your own journey as an adult learner from the

past to today. Think about your mentoring experiences and the individuals who made a

difference in your life and helped you to grow and develop.

•

•

•

•

•

•

Who were my mentors?

At what point in my journey did they come into my life?

What were those experiences like? (e.g. how did the experience enhance my learning;

what methods did the mentor/s use to create a positive learning environment)

What critical learning and changes in thinking did I gain from each of my mentors?

What did I learn about being a mentee?

What did I learn that could contribute to my own development as a mentor?

The following questions for mentors are modified from Zachary (2000).

Before the first meeting with your mentee, reflect on:

•

•

•

•

•

What information do you have about your prospective mentee?

What additional information do you need?

What questions will you ask your prospective mentee to gather this information?

What information can you gather from other sources? List sources and information that

you can gather.

What more do you need to know about your mentee as a learner in order to have a better

sense of his or her journey?

After the first meeting with the mentee, reflect on:

•

•

•

What insights does your prospective mentee’s journey raise for you about your

similarities and differences in life experiences and learning styles?

What differences in approaches and styles could potentially have a negative impact on

the mentoring relationship?

What actions or approaches could potentially have a positive impact on the mentoring

relationship?

Copyright © A. T. Wong & K. Premkumar 2007. Source: An Introduction to Mentoring Principles, Processes and Strategies for

Facilitating Mentoring Relationships at a Distance. http://www.usask.ca/gmcte/drupal/?q=resources

Contact angie.wong@usask.ca or kalyani.premkumar@usask.ca.

Negotiating Outcomes and Processes

The following questions for mentors are modified from Zachary (2000).

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

What specific outcomes does the mentee wish to achieve as a result of this mentoring

relationship?

Are the desired outcomes achievable within the availability of your time?

Are there other resources (human and other) that are necessary to achieve the desired

outcomes?

Are the desired outcomes capable of being measured?

What should the mentee know and be able to do as a result of the mentoring process?

In what ways can a successful relationship be evaluated?

What ground rules should we mutually subscribe to facilitate the mentoring

relationship?

What actions can be adopted to check the progress of the mentoring relationship?

Sample Ground Rules for a Mentoring Relationship

Mentors and mentees should determine which ground rules they will mutually abide by and

establish checkpoints to explore how well each side is complying with them.

•

•

•

•

•

•

We will manage our time well.

We will each participate actively in the mentoring process.

We will communicate openly and honestly while respecting our differences.

We will respect each other’s experience and expertise.

We will clearly identify the times and locations for us to meet.

We will safeguard confidentiality.

Confidentiality is a sensitive issue that merits deeper exploration. Mentors and mentees can

check their assumptions about confidentiality by answering yes, no, or not sure to the following

statements.

•

•

•

•

•

What we discuss between us stays there unless you give me permission to talk about it

with others.

What we discuss between us stays there as long as we are engaged in our mentoring

relationship.

Some issues will be kept confidential, while others may not. We will alert each other

about what needs to be kept confidential.

If there is a demonstrated need to know, I can disclose our conversations and other

element

That pertain to the mentoring relationship.

Copyright © A. T. Wong & K. Premkumar 2007. Source: An Introduction to Mentoring Principles, Processes and Strategies for

Facilitating Mentoring Relationships at a Distance. http://www.usask.ca/gmcte/drupal/?q=resources

Contact angie.wong@usask.ca or kalyani.premkumar@usask.ca.

REFERENCES

Albom, M. (1997). Tuesdays with Morrie. New York: Doubleday.

Alliance. Celebrating excellence. (1995). Alliance, an Association for Alternative Degree

Programs, and American Council on Education. Washington, DC: Alliance. (ED 402 510)

Anderson, E. M. & Shannon, A. L. (1988.) Towards a conceptualization of mentoring. Journal of

Teacher Education, 39(1), 38-42.

Bateson, M. C. (1989). Composing a life. New York: Atlantic Monthly Press.

Bennett, D., Hupert, N., Tsikalas, K., Meade, T., & Honey, M. (1998). Critical issues in the

design and implementation of telementoring environments. Centre for Children and Technology.

Retrieved January 26, 2006, from

http://www2.edc.org/CCT/admin/publications/report/09_1998.pdf.

Bierema, L.L., Merriam, S.B. (2002.) E-mentoring: using computer medicated communication to

enhance the mentoring process. Innovative Higher Education 26(3), 211-227.

Brookfield, S. (1986). Understanding and facilitating adult learning. San Francisco: JosseyBass.

Brown, Bettina Lankard. (2001). Mentoring and Work-Based Learning. Trends and Issues Alert

No. 29. Columbus, Ohio: ERIC Clearinghouse on Adult, Career, and Vocational Education.

Caffarella, R. S. (1992). Psychosocial development of women: Linkages of teaching and

leadership in adult education (Information Series No. 50). Columbus, OH: ERIC Clearinghouse

on Adult, Career and Vocational Education. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED

354386)

Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act of 1998 http://www.ftc.gov/ogc/coppa1.htm

Cravens, J. (2003). Online mentoring: Programs and suggested practices as of February 2001.

Journal of Technology in Human Services, 21(1–2), 85–109.

Daloz, L. (1986). Effective teaching and mentoring: Realizing the transformative power of adult

learning experience. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Daloz, L. (1999). Mentor: Guiding the journey of adult learners (Rev. ed.). San Francisco:

Jossey-Bass.

Dewey, J. (1916). Democracy and education: An introduction to the philosophy of education.

New York: The Free Press.

Copyright © A. T. Wong & K. Premkumar 2007. Source: An Introduction to Mentoring Principles, Processes and Strategies for

Facilitating Mentoring Relationships at a Distance. http://www.usask.ca/gmcte/drupal/?q=resources

Contact angie.wong@usask.ca or kalyani.premkumar@usask.ca.

The Electronic Emissary http://www.tapr.org/emissary/

Elluminate® http://www.elluminate.com/vroom/

Ensher, E.A., and Murphy, S.E. (1997). Effects of Race, Gender, Perceived Similarity, and

Contact on Mentor Relationships. Journal of Vocational Behavior 50(3), 460-481. (EJ 543 999)

Ensher, E. A., Heun, C., & Blanchard, A. (2003). Online mentoring and computer-mediated

communication: New directions in research. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 63, 264–288.

Gordon, J. R., & Whelan, K. S. (1998). Successful professional women in midlife: How

organizations can more effectively understand and respond to the challenges. Academy of

Management Executive, 12(1), 8-27.

Hansman, C. A. (Ed.). (2002). Critical perspectives on mentoring: Trends and issues

(Information Series No. 388). Columbus, OH: ERIC Clearinghouse on Adult, Career and

Vocational Education. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 354386)

Jossi, F. (1997). Mentoring in Changing Times. Training & Development 51(8), 50-54. (EJ 548

533)

Knowles, M. (1980). The modern practice of adult education: From pedagogy to andragogy (2nd

ed.). New York: Association Press.

LearnWell eMentors http://www.learnwell.org/

Lewin, K. (1951). Field theory in social sciences. New York: Harper & Row.

Lyons, W., Scroggins, D., & Rule, P. B. (1990). The mentor in graduate education. Studies in

Higher Education, 15(3), 277-285.

Mentor Center http://mentorcenter.bbn.com/

MentorNet www.mentornet.net

Miller, H., & Griffiths, M. (2005). E-mentoring. In D. L. DuBois & M. J. Karcher (Eds.),

Handbook of youth mentoring (pp. 300–313). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Murray, M. (1991). Beyond the myths and magic of mentoring: How to facilitate an effective

mentoring program. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

National Mentoring Partnership http://www.ed.gov/pubs/YesYouCan/sect3-checklist.html

http://www.albion.com/netiquette/book/index.html

Copyright © A. T. Wong & K. Premkumar 2007. Source: An Introduction to Mentoring Principles, Processes and Strategies for

Facilitating Mentoring Relationships at a Distance. http://www.usask.ca/gmcte/drupal/?q=resources

Contact angie.wong@usask.ca or kalyani.premkumar@usask.ca.

National Mentoring Center (2002). Perspectives on e-mentoring: A virtual panel holds an online

dialogue. National Mentoring Center Newsletter, 9, 5–12. Retrieved January 26, 2006, from

http://www.nwrel.org/mentoring/pdf/bull9.pdf.

Oswald, P. (1996). Distance Learning in Psychology. Paper presented at the 10th Annual

Conference on Undergraduate Teaching of Psychology, Ellenville, NY, March 1996. (ED 405

024)

Piaget, J. (1969). The mechanisms of perception. New York: Routledge Kegan Paul.

Ragins, B. R. (1997). Diversified mentoring relationships in organizations: A power perspective.

Academy of Management Review, 22(2), 482-521.

Saito, R. N. & Sipe, C. L. (2003). E-mentoring: The digital heroes campaign Year Two

Evaluation Results. Unpublished report prepared for MENTOR/National Mentoring Partnership

and AOL Time Warner Foundation

Stalker, J. (1996). Women mentoring women: Contradictions, complexities and tensions. In

Proceedings of the 37th Annual Adult Education Research Conference, USA. (ERIC Document

Reproduction Service No. ED 419087).

Hewlett Packard telementoring program (www.telementor.org)

Shea, Virgina (1994). Netiquette Albion Books.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1981). The genesis of higher mental functions. In J. V. Wertsch (Ed.), The

concepts of activity in Soviet psychology. Armonk, New York: Sharpe.

Zachary, L. (2000). The mentor’s guide: Facilitating effective learning relationships. San

Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Copyright © A. T. Wong & K. Premkumar 2007. Source: An Introduction to Mentoring Principles, Processes and Strategies for

Facilitating Mentoring Relationships at a Distance. http://www.usask.ca/gmcte/drupal/?q=resources

Contact angie.wong@usask.ca or kalyani.premkumar@usask.ca.

GLOSSARY

Andragogy: A term coined by the adult educator Malcolm Knowles used to refer to the

principles and processes used in facilitating learning among adults.

Apprentice model: a model of mentoring where the mentee observes the mentor and learns.

Boundary setting: Within the context of a mentoring relationship, the mentor and the mentee

attempt to clarify their expectations of their mutual roles and responsibilities so as to avoid

potential misunderstandings. The agreed boundary helps to define the limits of factors such as

access, time, and place.

Competency model: a model of mentoring where the mentor gives the mentee systematic

feedback about performance, progress, skills and expertise.

Confidentiality: An expectation or agreement that anything said or done within a relationship

such as mentoring will be kept private.

Elluminate®: a software that can be used to facilitate online learning and collaboration

http://www.elluminate.com/

e-mentoring: online or electronic version of mentoring.

Explicit knowledge: A more or less systematically organized set of values, procedures and

norms of practice that members of a professional community subscribe to as acceptable

professional conduct.

Formal mentor relationships: a type of relationship that is organized by workplace and

organizations; not necessarily spontaneous.

Ground rules: Rules of procedure to guide interaction between mentors and mentees.

Informal mentor relationships: a type of relationship that is established spontaneously; largely

psychosocial that helps enhance the mentee’s self esteem and confidence by providing emotional

support and discovery of common interests.

Learning styles: A concept that refers to certain preferred patterns of behavior according to

which individuals approach learning experiences, including the ways in which individuals take in

information and develop new understanding and skills.

Mentee: also known as protégé; one who is being mentored.

Mentor: trusted counselor or teacher.

Copyright © A. T. Wong & K. Premkumar 2007. Source: An Introduction to Mentoring Principles, Processes and Strategies for

Facilitating Mentoring Relationships at a Distance. http://www.usask.ca/gmcte/drupal/?q=resources

Contact angie.wong@usask.ca or kalyani.premkumar@usask.ca.

Netiquette: formed from network etiquette; guidelines for online conduct to promote pleasant,

agreeable interactions.

Reflective model: a model of mentoring where the mentor helps the mentee become a reflective

practitioner; an important characteristic being the ability to critically analyze practice.

Tacit knowledge: A term coined by Michael Polyani to describe the kind of experience-based

knowledge that expert practitioners usually hold in their heads but find difficult to verbalize to

others.

Tutoring: provision of academic and remedial assistance in a particular area with a sole focus on

competence.

Zone of proximal development: refers to the difference between an individual solving a

problem independently and solving a problem together with a peer who is more advanced in

knowledge or skills.

Copyright © A. T. Wong & K. Premkumar 2007. Source: An Introduction to Mentoring Principles, Processes and Strategies for

Facilitating Mentoring Relationships at a Distance. http://www.usask.ca/gmcte/drupal/?q=resources

Contact angie.wong@usask.ca or kalyani.premkumar@usask.ca.

An Introduction to Mentoring Principles, Processes, and Strategies for Facilitating

Mentoring Relationships at a Distance

A.T. Wong

K. Premkumar

PART TWO

Mentoring at a distance

Technology has opened the way for mentoring to occur without the mentor/s and

mentee/s being physically present in the same room.

Online or electronic version of mentoring, variously referred to as e-mentoring,

electronic mentoring, telementoring, cyber mentoring, virtual mentoring or online ementoring is the online or electronic version of mentoring. Bierema and Merriam (2002)

define e-mentoring as "a computer medicated, mutually beneficial relationship between a

mentor and a protégé which provides learning, advising, encouraging, promoting, and

modelling, that is often boundaryless, egalitarian, and qualitatively different than

traditional face-to-face mentoring”.

E-mentoring is increasingly being used in schools to pair teachers and learners with

subject-matter experts in order to provide advice, guidance and feedback on learning

projects (e.g. Mentor Center, The Electronic Emissary, LearnWell, Brown, 2001).

Organizations, especially those with offices across the country and around the world,

utilize technology to connect mentors and protégés (Jossi 1997). It is also being used to

facilitate distance learning and improve retention and completion of degrees by distance

learners (Alliance 1995; Oswald 1996).

Typically email is used, but other tools such as videoconferencing, discussion boards, and

instant messaging may also be utilized. With the availability of a variety of newer

technological tools such as web cams and Elluminate® software it is possible for mentormentee communications to take place in many innovative ways.

No matter how the communication occurs, it is important to remember that e-mentoring

has the same purposes as traditional mentoring except that technology is used to facilitate

mentoring relationships. However, one should not be closed to the idea that e-mentoring

is qualitatively different and might provide as yet undetermined contexts and exchanges

that may not be possible to replicate in traditional mentoring relationships.

Categories of e-Mentoring

E-mentoring falls into two broad categories, mentoring for educational development and

mentoring for career development. Mentoring for educational purposes involves bringing

students in contact with subject matter experts in a classroom setting, online or a

Copyright © A. Wong & K. Premkumar 2007. Source: An Introduction to Mentoring Principles, Processes and

Strategies for Facilitating Mentoring Relationships at a Distance. http://www.usask.ca/gmcte/drupal/?q=resources

Contact angie.wong@usask.ca or kalyani.premkumar@usask.ca.

Mentoring/Mentoring at a Distance Modules: July 13, 2007

combination of both. One example is the Hewlett Packard telementoring program

(www.telementor.org), which has been successfully operating since 1995. In this case,

experts from across the world communicate with school children to improve mathematics

and science competencies and to increase the number of females and minorities studying

and teaching these subjects. This endeavour has included wider exposure to career

possibilities, experiential learning, improvement in math, and science skills.

Other prominent educational telementoring programs include one supported by the

National Science Foundation that links young women in science, engineering and

computing to experts in the field (The Telementoring Project

http://www.edc.org/CCT/telementoring/) with an aim to increase the presence of women

in male-dominated fields. Another successful program similar to that supported by the

National Science Foundation is that of MentorNet (www.mentornet.net).

E-mentoring is becoming increasingly important in career development due to the

changing face of workplace. Freelancing, consulting and work-from-home arrangements

are becoming commonplace with reduced opportunities of contact between potential

mentors and mentees. Many organizations are looking to telementoring for building

relationships.

Types of e-Mentoring

E-mentoring may take different forms. An expert may mentor a single student or a group

of mentees. Alternatively, a group of mentors may be assigned to one mentee, i.e. team

mentoring. The later is particularly rich as the mentee has access to mentors who can

address more facets of their lives. Also, the time commitment and pressure on an

individual mentor is reduced. Tripartite e-mentoring is an innovative type of mentoring

where in addition to the usual adult-youth relationship, the mentee serves as a mentor to a

younger person. In this type of relationship the individual has the experience of being

both a mentor and a mentee – a situation that can improve self-esteem, foster

responsibility and encourage involvement in the community. Another form of mentoring

is peer mentoring, where one participant mentors another colleague or one student

mentors another student.

Advantages provided by e-Mentoring

The use of technology in mentoring provides a number of advantages and yet also poses

many challenges.

Inherent advantages of the medium

The written medium of conversation allows for spontaneity and flexibility. Since online

communication does not require instant reaction, it allows for more thoughtful interaction

between mentor and mentee. It is also possible to exchange large amount of information

in a short span of time.

Copyright © A. T. Wong & K. Premkumar 2007. Source: An Introduction to Mentoring Principles, Processes and

Strategies for Facilitating Mentoring Relationships at a Distance. http://www.usask.ca/gmcte/drupal/?q=resources

Contact angie.wong@usask.ca or kalyani.premkumar@usask.ca.

Mentoring/Mentoring at a Distance Modules: July 13, 2007

Geographic considerations

Telementoring does not require travel and provides opportunities for mentors and

mentees separated geographically to interact. For example, a mentee from Canada could

interact with a mentor in Australia. Provided that the technology is accessible and

available, the mentor and mentee are not confined to a physical space and interactions

can be initiated or continued from anywhere – while traveling, or in a public space such

as a restaurant, or library.

Time considerations

Telementoring is attractive for mentors and mentees separated temporally, increasing

opportunities to interact by making it possible for interactions to occur at any time,

synchronous or asynchronously. Thus it lessens or eliminates any scheduling or time

zone issues.

Cost effectiveness

With telementoring it is possible to send any number of messages of any length with

minimal cost.

Anonymity

Since the relationship is largely computer-mediated, there is a certain degree of

anonymity from the part of both the mentees and mentors that may facilitate more open

exchange.

Bias reduction

It can lessen biases potentially inherent in physical relationships. E-mentoring breaks

down barriers such as nationalities, size of organizations, age, gender and appearance that

may exist in face-to-face mentoring (conversely, these barriers could also function as

identifiers and help build relationships, see below. Either way, this aspect does not factor

into e-mentoring to the same degree).

Process enhancements

The technological tools available for use during mentoring allow mentors to utilize a

variety of strategies to match mentee needs and learning styles.

Convenience

People who prefer not to mentor face-to-face may be willing to do so via their home or

work computers.

Improved Access

Because of its flexibility, e-mentoring allows for mentors who have a disability, mobility

issue, home obligation or work schedule to participate in a program. Telementoring has

the potential to equalize access to mentors for rural and marginalized students.

Copyright © A. T. Wong & K. Premkumar 2007. Source: An Introduction to Mentoring Principles, Processes and

Strategies for Facilitating Mentoring Relationships at a Distance. http://www.usask.ca/gmcte/drupal/?q=resources

Contact angie.wong@usask.ca or kalyani.premkumar@usask.ca.

Mentoring/Mentoring at a Distance Modules: July 13, 2007

Generational gaps

E-mentoring encourages young people to consider being a mentor. For example, more

young people use internet resources with ease and may find it preferable to communicate

online.

Ecological considerations

Online mentoring may be considered to be environmentally friendly as it reduces the

need for travel and use of paper.

Mentoring at a distance – special challenges

While e-mentoring provides numerous advantages, a key question that needs to be

answered is whether the relationships – the essence of mentoring – are optimized and

well-maintained. Is care and concern clearly present in the relationship? Is the

relationship personal and mutually satisfying? Is it based on understanding, appreciation

and respect? Does technology add yet another dimension to this relationship?

Along with advantages, e-mentoring poses special challenges. These include a higher

potential for miscommunication/misinterpretation, specific literacy requirements, issues

of security and confidentiality, possible increase in time commitment, formation of

weaker ties, slower progression of relationships, and the need for additional skills and

resources. In addition, the issue of gender differences in online communication styles,

and similar concerns involving culture, race and ethnicity may serve as potential barriers

to effective communication, which is a vital element in any mentoring relationship.

Miscommunication/ misinterpretation

One of the issues introduced by mentoring conducted through technology is that it lacks

the full range of communication cues that exist in direct face-to-face interactions.

Therefore, there is a greater risk for misunderstanding and misinterpretation in this type

of communication. For instance, mentors and mentees can misinterpret attempts at

humour and sarcasm. The tone of the message may be misread as negative when it was

not meant to be so. Furthermore, online communication has a tendency to lower the

inhibitions of the communicator leading them to write things that they may hesitate to say

face-to-face.

Another common cause of misinterpretation is delayed responses to messages. Since ementoring is typically text-based, asynchronous and relatively fast, there is an

expectation for responses from participants to be quick. A busy mentor may think nothing

of letting a few days elapse before responding to a message. But this may be

misinterpreted by a mentee as a lack of interest, sign of anger or rejection.

Copyright © A. T. Wong & K. Premkumar 2007. Source: An Introduction to Mentoring Principles, Processes and

Strategies for Facilitating Mentoring Relationships at a Distance. http://www.usask.ca/gmcte/drupal/?q=resources

Contact angie.wong@usask.ca or kalyani.premkumar@usask.ca.

Mentoring/Mentoring at a Distance Modules: July 13, 2007

With the addition of web-cam and the ability to see each other, miscommunications can

be overcome to some extent, but here, communication has to occur synchronously. Use of

emoticons and training in netiquette are two ways by which interactions can be

improved. It is essential for both mentors and mentees to be trained in online

communication. Refer to the appendix at the end of this paper for the following

information and tips that can help you become a better online communicator:

1. Common emoticons and abbreviations that can be used during

communications.

2. Information on netiquette – etiquette while using the internet.

3. Tips to help mentors communicate better online.

Despite the use of such strategies, the question of whether digital technology promotes

the depth and breadth of relationships that face-to-face communications provide remains

vital, and an unanswered question.

Literacy requirements

One hidden challenge in e-mentoring is the question of literacy. In telementoring, the

participants have to be careful and rapid readers. Also, the participant’s level of

proficiency in the English language of communication may serve as an impediment to

communication. Despite the flexibility of time inputs for text composition, and the

availability of grammar and spell-check programs, elevated writing ability tends to be

required.

Technology by itself can be intimidating to some. If a person is not familiar with using

technology to communicate (e.g. unfamiliarity with the unique culture of online

exchanges, the rules of “netiquette,” or the vagaries of computer viruses), this may

function as a communication inhibitor and create anxiety for the participant.

Security and Confidentiality

Managers of programs have legitimate concerns about data security and confidentiality,

especially where the participants are part of a vulnerable population. Participants may be

inhibited from making authentic disclosures or sharing their mistakes (an important

strategy for building trust) because of their awareness that online mentoring creates

written records. Also, as part of the business culture, adults tend to be discouraged from

making statements that could be misinterpreted in a court of law. Another confidentiality

issue that may inhibit communication is the fact that sponsoring agencies and employers

have the legal right to open and read electronic communications.

Potential increase in time commitment

Because of its flexibility, telementoring can add more activity into a person’s already

busy schedule. In situations where the hardware is slow, a considerable amount of time

can be wasted connecting to the network.

Copyright © A. T. Wong & K. Premkumar 2007. Source: An Introduction to Mentoring Principles, Processes and

Strategies for Facilitating Mentoring Relationships at a Distance.http://www.usask.ca/gmcte/drupal/?q=resources

Contact angie.wong@usask.ca or kalyani.premkumar@usask.ca.

Mentoring/Mentoring at a Distance Modules: July 13, 2007

Creation of weaker ties

There is evidence to show that exclusively online relationships can compete with, and

ultimately supplant, closer ties (Saito & Sipe, 2003). Telementoring tends to establish

weak ties characterized by less contact, more narrow focus, and more superficial and

easily broken bonds as opposed to strong ties characterized by frequent contact across

many life areas, deep affection and mutual obligation. Understandably, strong ties are

associated with better social and psychological outcomes.

Slower progression of relationships

Relationships in telementoring tend to progress at a slower rate because of the reduced

availability of information that helps to form lasting impressions, such as race, age,

physical appearance, emotions, and personal disclosures. Occasionally, network and

computer breakdown can prevent contact and slow down progress.

Need for additional skills and resources

With telementoring, access to technology is assumed. However, not everyone has access

to the internet. Inaccessibility is more common in the less educated and those from lowincome communities. With reduced access, there is less comfort and familiarity with

computers. All this creates barriers to launching programs in areas and for people who

may need it the most. In addition, the issue of technology costs should not be ignored.

Gender differences in online communication styles

Studies show that the differences in the way men and women communicate online could

serve as a potential barrier (Ensher 1997). While men communicate to the point and tend

to be factual, the communications of women tend to resemble face-to-face conversations.

Culture, race and ethnicity

If proper attention is not paid to gender, culture, sexual orientation and racial issues while

communicating online, it may serve as a barrier to building relationships.

Strategies for Establishing e-Mentoring Programs and Overcoming Challenges

The potential benefits of e-mentoring in higher education has prompted many

organizations to establish formal e-mentoring programs. Some strategies for establishing

e-mentoring programs are summarized.

Below are some tips for overcoming challenges in e-mentoring (adapted from to the

National Mentoring Partnership http://www.ed.gov/pub/YesYouCan/index.html)

Copyright © A. T. Wong & K. Premkumar 2007. Source: An Introduction to Mentoring Principles, Processes and

Strategies for Facilitating Mentoring Relationships at a Distance. http://www.usask.ca/gmcte/drupal/?q=resources

Contact angie.wong@usask.ca or kalyani.premkumar@usask.ca.

Mentoring/Mentoring at a Distance Modules: July 13, 2007

State purpose and establish a long-range plan

Once the purpose of the e-mentoring program is clearly identified with input from all

stakeholders, the organization’s readiness and capacity to create and sustain such a

program has to be established. A realistic, attainable, and adaptable operational plan has

to be formed. The goals, objectives, timelines and accountability for all aspects of the

plan have to be established. Funding and resource development plans have to be mapped

along with the program evaluation plan.

Incorporate elements of successful mentoring practice into e-mentoring situations

It is important to remember that e-mentoring is the same as traditional mentoring except

that technology is used. As such, best practices of traditional mentoring have to be

incorporated and adapted to e-mentoring.

Decide on what technology to use

Electronic mail, whether addressed individually or to a group distribution lists, is the

primary and common technology used in e-mentoring. It is advantageous as it is textbased, and asynchronous. It also results in messages that appear in the participants email

inbox, thus making it difficult for participants to ignore the conversations.

Web-based bulletin boards and chat lines may also be used, but both require more of the

participants. Here, participants have to be motivated and disciplined to access the bulletin

board or chat system to participate. In addition, chat systems, being synchronous, may

discourage participation by individuals who type slowly, or cannot access the system

because of scheduling conflicts.

Identify a technology implementation strategy

Taking into account the goals of the program and the participants, an appropriate

communication system has to be identified.

The communication system has to be available to all participants – both mentors and

mentees should have free access to the communication system. Take into account that if

participants’ accessibility to computers is only in the workplace, this may restrict

duration and frequency of communication. The participants may be able to communicate

only on weekdays during working hours. The communication system also has to be safe

for all participants – policies regarding privacy and security of the participant’s data and

communication have to be put in place. Identify the areas that may require reference

checks (e.g. criminal record checks). A code of conduct, and a method for archiving

emails to meet the safety and/or evaluation needs of the program will need to be

established (see Netiquette in the appendix section).

Copyright © A. T. Wong & K. Premkumar 2007. Source: An Introduction to Mentoring Principles, Processes and

Strategies for Facilitating Mentoring Relationships at a Distance. http://www.usask.ca/gmcte/drupal/?q=resources

Contact angie.wong@usask.ca or kalyani.premkumar@usask.ca.

Mentoring/Mentoring at a Distance Modules: July 13, 2007

A process for addressing and raising concerns relating to safety and privacy also has to be

established. Advise participants to never respond to messages that are suggestive,

obscene, belligerent, threatening, or that make them feel uncomfortable. Encourage them

to contact the designated person in your program if they encounter such messages.

Advise online participants never to give out personal information online (their home

address, their phone number, etc.). Advise participants never to meet anyone in person

they have met online, even in conjunction with your organization's online program,

except at officially sponsored events. This is generally recognized when dealing with

young people, but is also important to incorporate where program involve people

unfamiliar or apprehensive about the use of technology.

Establish a recruitment plan for mentors and mentees

Initially, the expectations and benefits of an e-mentoring program have to be identified

and used to market the program to the target population.

Identify eligibility screening for mentors and mentees

Chart out the application process and review.

List suitability criteria given the purpose and goals of the program. In addition, take into

account the characteristics of an effective mentor. It is important to establish successful

completion of training and orientation as one criteria. Refer to the following resources

found in the appendix section. These resources can help you with establishing suitability

criteria:

Considerations for program coordinator brokering mentor-mentee relationships:

Characteristics of a effective mentor.

Criteria that may be considered when brokering mentor-mentee relationship:

Common Suitability criteria for mentors.

Identify a strategy for matching mentors and mentees

Depending on the program goals, appropriate criteria have to be established. Some

criteria that may be considered while matching include gender, age, race, language,

availability, needs, interest, geography, individual preferences of mentor and mentee, life

experience, and/or temperament.

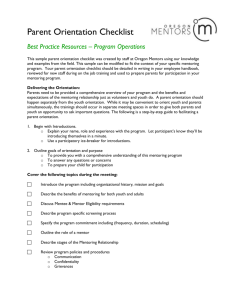

Orient both mentors and mentees separately

In most cases, initial orientation will have to occur online in the form of email messages.

In the orientation, the following aspects will need to be addressed:

•

•

•

•

Program overview and goals

Expectations and restrictions

Description of eligibility, screening process, logistics and suitability requirements

Description of how the technology works and equipment needed

Copyright © A. T. Wong & K. Premkumar 2007. Source: An Introduction to Mentoring Principles, Processes and

Strategies for Facilitating Mentoring Relationships at a Distance. http://www.usask.ca/gmcte/drupal/?q=resources

Contact angie.wong@usask.ca or kalyani.premkumar@usask.ca.

Mentoring/Mentoring at a Distance Modules: July 13, 2007

•

•

•

•

•

If required, training in the use of technology identified has to be provided

The level of commitment expected in terms of time, energy, flexibility, and

frequency

The benefits and rewards of participation

Summary of program policies, including those governing privacy, reporting,

communications and evaluation.

Safety and security, especially around the use of the internet.

Establish a training curriculum for all mentors and mentees

The training should be provided by qualified program trainers, preferably face-to-face. If

face-to-face training is not possible, training may be provided in the form of online

handbooks. During training, activities that build commitment to the program should be

planned and conducted. It is important to develop the appropriate skills and competency

for online communications. Training modules should address cultural/heritage sensitivity,

and role descriptions. Participants should be made aware of any problem-solving

resources that are available. It is important to provide support materials and ongoing

training as necessary.

Ascertain a monitoring process

The program planners have to communicate regularly and consistently with the staff,

mentors and mentees. A tracking system for ongoing assessment and monitoring has to

be in place. Special mentoring software exists for facilitating telementoring relationships.

Such software provides a centralized area where mentors and mentee communications are

directed, conducted and monitored. It also provides an area for discussion between

mentors and sharing of experiences between mentees. As well, it directs communications

from the mentor to mentee in a safe environment. The area can also provide resources for

both mentees and mentors in building relationships, and proficiencies in online

communications among others. It can also provides separate areas for discussion between

mentors and sharing of experiences between mentees.

See “Additional e-Mentoring Resources” in the appendix section.

Create a support, recognition and retention strategy

To support mentors and mentees, a mechanism has to be put in place to manage

grievances, re-matching, interpersonal problem solving, crisis management and provision

of closure to prematurely-ended relationships. The provision of separate discussion

boards for mentors and mentees is one aspect of providing ongoing peer support. The

presence of a program coordinator is another. In addition, there should be a system for

providing ongoing recognition and appreciation. One supportive strategy is to have a

formal kick-off for the program, followed by ongoing updates where stakeholders are

kept informed on the program and progress. This may be communicated to them in the

form of newsletters or other communications.

Copyright © A. T. Wong & K. Premkumar 2007. Source: An Introduction to Mentoring Principles, Processes and

Strategies for Facilitating Mentoring Relationships at a Distance. http://www.usask.ca/gmcte/drupal/?q=resources

Contact angie.wong@usask.ca or kalyani.premkumar@usask.ca.

Mentoring/Mentoring at a Distance Modules: July 13, 2007

Determine steps for closure

Closure may be in the form of private and confidential exit interviews with mentors and

mentees. Remember to provide assistance to the mentees in defining the next steps to

follow the program.

Establish strategies for program evaluation

Develop a plan to measure program process. Select indicators of program implementation

viability and participant fidelity, such as, training hours, meeting frequency and

relationship duration; and develop a system for collecting and managing specified data.

Develop a plan to measure expected outcomes: specify expected outcomes; select

appropriate instruments to measure outcomes, such as questionnaires, surveys and

interviews; and implement an evaluation design.

Create a process to reflect on and disseminate evaluation findings. Refine the program

design and operations based on the findings. Develop and deliver reports to program

constituents, funders and the media (at minimum yearly; optimally, each quarter).

Conclusion

Mentoring is an intentional, nurturing and insightful process that provides a powerful

growth experience for both the mentor and mentee. The mentoring relationship

progresses through four stages—preparing, negotiating, enabling and reaching closure.

All four phases have to be carefully considered for successful programs. Due to its

availability and accessibility, technology is increasingly used in the mentoring process.

While the use of technology provides a number of advantages, the many challenges that it

poses have yet to be completely overcome. It is important to realize that the purpose and

goals of the mentoring program and the human nature of the mentoring relationships

must drive the mentoring process, rather than the advantages provided by technology.

A number of questions relating to e-mentoring still remain unanswered. Are the goals and

outcomes of e-mentoring the same as traditional mentoring? Is it possible to develop a

deep and close relationship between mentor and mentee online? What steps result in

effective e-mentoring relationships? What are the situations where online-mentoring is

more appropriate? What effect does technology have on the quality and nature of thementoring process? What can we learn from current e-mentoring relationships?

While experts agree that exclusively online relationships should be resorted to only when

face-to-face connections are unavailable, unfeasible or inappropriate, a combination of

face-to-face meetings supplemented by online communications can offer the best of both

worlds.

Copyright © A. T. Wong & K. Premkumar 2007. Source: An Introduction to Mentoring Principles, Processes and

Strategies for Facilitating Mentoring Relationships at a Distance. http://www.usask.ca/gmcte/drupal/?q=resources

Contact angie.wong@usask.ca or kalyani.premkumar@usask.ca.

Mentoring/Mentoring at a Distance Modules: July 13, 2007

_______________________________________________________________________

Additional Resources on e-Mentoring

The Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act of 1998. Available at:

http://www.ftc.gov/ogc/coppa1.htm.

Friedman, A. A., Zibit, M, & Coote, M. (2004). Telementoring as a collaborative agent

for change. Journal of Technology, Learning, and Assessment, 3(1). Available from

http://www.jtla.org

International Telementor Program Evaluation Results from Teacher, Mentor, and Student

Surveys April 2002 – June 2005 Research and Development Center for the Advancement

of Student Learning Co-Directors: Michael DeMiranda, Ph.D. and Ellyn Dickmann,

Ph.D. http://www.telementor.org/research/Research_2002-2005.pdf Evaluation report

August 2005

Yes, You Can: A Guide for Establishing Mentoring Programs to Prepare Youth for

College http://www.ed.gov/pubs/YesYouCan/index.html

Zappie-Ferradino, Kristi. Incorporating effective practices for Successful e-Mentoring

http://nationalserviceresources.org/epicenter/practices/index.php?ep_action=view&ep_i

d=939

MentorPlace at http://www.mentorplace.org/ddm/mpthome.htm has very useful

guidelines and tips for e-mentoring.

The Center for Children and Technology (CCT) continues to support organizations

interested in learning about how to set up this kind of program and the value of such

programs for young women. See http://www.edc.org/CCT/telementoring/

A guide to program mentor listings is available at:

http://www.peer.ca/mentorprograms.html

Systers is the world’s largest email community of technical women in computing. Many

Systers members credit the list for helping them make good career decisions, and steering

them through difficult professional situations. Systers’ is a forum for all women involved

in the technical aspects of computing. See http://anitaborg.org/initiatives/systers

Mighty Media Mentors is a free, public service that enables teachers to mentor each other

via email on issues such as improving teaching techniques and troubleshooting classroom

problems. See www.mightymedia.com/mentors

Copyright © A. T. Wong & K. Premkumar 2007. Source: An Introduction to Mentoring Principles, Processes and

Strategies for Facilitating Mentoring Relationships at a Distance.http://www.usask.ca/gmcte/drupal/?q=resources

Contact angie.wong@usask.ca or kalyani.premkumar@usask.ca.

Mentoring/Mentoring at a Distance Modules: July 13, 2007

DO-IT serves to increase the participation of individuals with disabilities in challenging

academic programs and careers. It promotes the use of computer and networking

technologies to increase independence, productivity, and participation in education and

employment. See http://www.washington.edu/doit/Brochures/Programs/scholars.html

Copyright © A. T. Wong & K. Premkumar 2007. Source: An Introduction to Mentoring Principles, Processes and

Strategies for Facilitating Mentoring Relationships at a Distance. http://www.usask.ca/gmcte/drupal/?q=resources

Contact angie.wong@usask.ca or kalyani.premkumar@usask.ca.

Mentoring/Mentoring at a Distance Modules: July 13, 2007

Appendix

Common emoticons and abbreviations that can be used during communications

(adapted from http://www.mentorplace.org/ddm/MPTCCommunication.htm)

Emoticons and abbreviations are used in electronic communications to compensate for

the lack of body language that helps interpret communications.

Emoticons are characters that resemble a face turned on its side, that are added at the end

of sentences to reflect emotions. Some common emoticons that can be used during

mentor-mentee communications are:

:-) or : ) Smile; happy

: ( or :-< Sad

;-) Winking smile

:-\ Undecided

:-o Shocked

|-| Boredom (sleepy)

:-# My lips are sealed.

:-I Hmmm.....

:-p Sticking my tongue out

(-: I am left-handed.

{:-) I part my hair in the middle.

-:-) I have a mohawk.

8-) I wear glasses.

::-) I wear bifocals.

*<;-) Party; celebration; happy birthday

To save time and thereby the cost of using technology (cost of text messaging using cell

phones and internet connections) and reduce reading, people have resorted to using

abbreviations to communicate electronically. Such abbreviations are quite common in

newsgroup postings, instant messaging and blogs. Below are some common

abbreviations. The Netlingo website (http://www.netlingo.com/emailsh.cfm) may be

accessed for a comprehensive list of abbreviations, if a mentor or mentee has difficulty

understanding an abbreviation used by a participant.

U = you

2 = to

4 = for

<g> Grinning, smiling

<vbg> Very big grin

<l> Laughing

Copyright © A. T. Wong & K. Premkumar 2007. Source: An Introduction to Mentoring Principles, Processes and

Strategies for Facilitating Mentoring Relationships at a Distance. http://www.usask.ca/gmcte/drupal/?q=resources

Contact angie.wong@usask.ca or kalyani.premkumar@usask.ca.

Mentoring/Mentoring at a Distance Modules: July 13, 2007

< Sighing

<jk> Just kidding

<> No comment

B/C = because

BFN Bye for now

BTW = by the way

CYA = see ya (see you)

G2G = got to go

J/K = just kidding