University of Saskatchewan Faculty Survey on Attitudes towards Teaching and Learning 2009

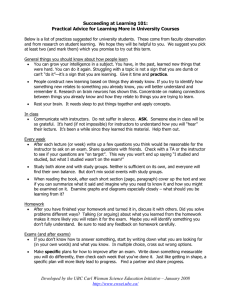

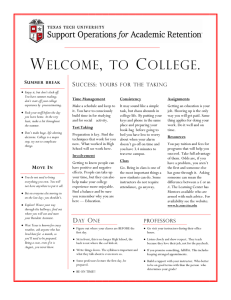

advertisement