Enthusiasm Conquers the Killjoys: A Way to Enhance Student Learning

advertisement

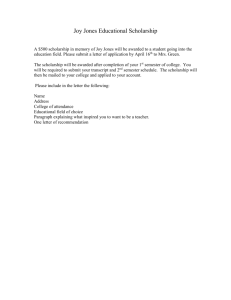

V o l u m e 1 • I s s u e 5 • October 2 0 0 2 An International Forum for Innovative Teaching CONTENTS 1 Commentary Deborah Frazier Jennifer Methvin 3 Integrating Theory and Concepts with Application in a Capstone Business Administration Course W. Kevin Baker, Ph.D. 5 Teaching Our Students the Language of Scholarship Robert W. Barnett Philip T. Greenfield 7 Generating Effective In-Class Discussions Calvin S. Kalman, Ph.D. 9 Motivating Students to Achieve: Six Strategies for Success Nichola D. Gutgold, Ph.D. 10 The Story of Your Name Kim Cuny 12 Meet the Authors • • • • • • • • • • • C O M M E N T A R Y Enthusiasm Conquers the Killjoys: A Way to Enhance Student Learning Deborah Frazier Vice Chancellor of Academic Affairs dfrazier@uaccb.edu Jennifer Methvin Instructor of English jmethvin@uaccb.edu University of Arkansas Community College at Batesville Batesville, Arkansas In his 1998 book, The Courage to Teach, Parker J. Palmer aptly describes successful professors: “I am a teacher at heart, and there are moments in the classroom when I can hardly hold the joy” (p. 1). Joy. Palmer used the word joy. Because it is difficult to define, much less objectify and quantify, joy and its cousins enthusiasm, thrill, passion, and fervor, have enjoyed little in-depth treatment in most explorations of teaching effectiveness and subsequent student learning. Ask any students, however, to talk about a teacher from whom they have learned much, and they describe an impassioned instructor with a love for her content area and for her students. Spend fifteen minutes observing any instructor who has been deemed “highly effective” by awards, student evaluations, course outcomes, and the like, and you will find a person who loves his job, is enthralled by his content area, and radiates enthusiasm in the classroom. Most know that instructor enthusiasm is a key element in effective teaching. Yet for many faculty, the thrill of teaching is gone. Largely this loss is due to some obstacle or obstacles that block these faculty from their joy. In our exploration of the importance of instructor enthusiasm in student learning, we have come to call these obstacles “killjoys.” In order to maintain teaching integrity, instructors have a responsibility to conquer the killjoys and reclaim the thrill of teaching. If those of us who teach want to continue to engage students in learning, maintaining our enthusiasm is as much our responsibility as keeping abreast in our content area and developing effective approaches for our classroom, things most dissatisfied instructors do not do anyway. Below are a few of the killjoys we have discovered in our own teaching careers and a few strategies for incarcerating those killjoys. We hope this discussion leads others to reclaim their thrill for teaching and thereby become more successful professors. Memory. In his “Hooked on Music,” Mac Davis sings a series of scenarios depicting a young man as he becomes, as the title implies, “hooked on music, hooked on music from that moment on.” What a long way we would go in maintaining our love for teaching if we, like Davis, kept handy a list of moments of pure teaching joy. Perhaps our biggest killjoys are bad moments and poor memories. continued on pg. 2.......... Enthusiasm Conquers the Killjoys. continued from pg. 1.......... The Successful Professor™ (ISSΝ 03087) is published 6 times a year by Simek Publishing LLC PO Box 1606 Millersville, MD 21108 See our website at www.thesuccessfulprofessor.com for Subscription Rates, Disclaimer, and Copyright Notice. Stanley J. Kajs Editor/Publisher Contact us at editor@thesuccessfulprofessor.com • • • • • • • • • • • • Would you like to share your teaching successes with your colleagues from other colleges and universities? If so, then submit an article describing your most effective teaching strategy or technique to The Successful Professor™. Visit our website to view the Guidelines for Articles. www.thesuccessfulprofessor.com The Successful Professor™ Most of us, unfortunately, dwell on the negative. Certainly, instructors should analyze bad teaching moments, but wallowing in failure can temper enthusiasm. Even when things are going well, those of us who have been in the classroom for some years can become desensitized to the wonder of student learning. We must find ways to remind ourselves of the important and profound nature of our profession. We suggest dwelling on those moments of teaching brilliance. Like Mac Davis, create a list of memories of when you became hooked on teaching, moments when, as Parker Palmer says, “things were going so well you knew you were born to teach” (p. 67). Share these memories with colleagues and drag them out of your memory occasionally just for pure enjoyment. Encourage colleagues to do the same, and share, share, share. The best faculty meeting we ever attended centered around everyone narrating a joyous teaching moment. Even taciturn and disgruntled faculty shared and smiled. Take time to remember the good work you do, and you will conquer this killjoy. Duty and Responsibility. Involved faculty members are easy to identify. They are the faculty who never say no. They serve not only on faculty committees but also as chairpersons. They are faculty advisors to student organizations and are the first to volunteer for community service projects. They do this for the intrinsic value these activities add to their lives. They might also garner the slightest hope that they are modeling desirable behavior. As we place all of these teaching functions, personal commitments, and institutional responsibilities in perspective, please note it is okay to say no. Know it will be okay that you are not chairperson this semester. Co-sponsor the student organization and let another know the joy this can bring. Choose the one activity that brings the greatest reward and learn to say no to the others. Routine. When an instructor has taught the same world literature class fifteen times in the VOLUME 1 • ISSUE 5 past ten years, that teaching has become routine, and routine can be a killjoy. Not having to start from scratch each time we step into the classroom is a blessing. However, never creating anything new will led us to boredom, and bored instructors are not effective instructors. Despite the heavy workload most faculty carry, we suggest continually breaking the routine by incorporating something new into each course each semester and making that something new very exciting for yourself. Last semester, for instance, that world literature instructor created a multi-media presentation which used 1960s and 1970s song lyrics to lead students to an understanding of the formal aspects of Romanticism poetry. Recording the songs for the presentation at 11:00 p.m. was not an imposition on sleeping time: it was a sing-fest. Surfing the web for confirmation that the memory had the lyrics right was not a dreaded task: it was a marvel at song-writing genius. Hearing students guffaw at the old music while finally coming to an understanding of the importance of metaphor and alliteration was not an embarrassment or a humdrum routine: it was teaching, an extremely thrilling job. The break in routine could be simple, like adding a new topic to an old course, or it could be consuming, like developing a new course or participating in an alternative instructional method. Whatever the strategy you choose, maintain enthusiasm by combating boredom. Workload. Within the college culture, faculty wear many hats. They serve on division, faculty, and institutional committees. They are mentors, advisors, and counselors. These services are in addition to the main focus of their employment, teaching. Teaching involves development, delivery, and assessment time. The art of time management is a required skill for the joyous faculty member. In Getting Things Done, Davis Allen outlines a method continued on pg. 3.......... 2 Enthusiasm Conquers the Killjoys. continued from pg. 2.......... for successfully reducing stress in project management. The method involves reviewing the project to determine if action is required. If action is required, take the next step. This may be as simple as filing a document or as complex as creating a timeline for completion. Once the initial action is taken, the project is forwarded to the “next action category.” Allen indicates that as projects are placed in the next action category, they are reviewed to ensure advancement. If initial evaluation concludes that no further action is required, these projects become “non-actionable transaction” items, and the project completion is achieved. The non-actionable transaction may lead you straight to the recycling bin. Climate. While very little has been written about faculty enthusiasm, much has been written about institutional climate and faculty dissatisfaction. Faculty dissatisfaction can diminish student learning, and a given institutional climate can dissatisfy faculty. Many instructors list their administrations, systems, state-mandates, accreditation requirements, fellow faculty, and a myriad of other items as killjoys. What is important to remember is that we can choose to be victims, or we can react with intelligence. Do not let the situation outside the classroom kill the joy within. Attitude. In Wake Up Calls, Joan Lunden states that “attitudes are contagious. Is yours worth catching?” (p. 7). As professional educators, we must realize the power of attitudes in lecture halls, offices, and walkways on our campuses. Lunden quotes Amy Tan with this statement: “If you can’t change your fate—change your attitude” (p. 86). Be reminded, we hold the power of change within us. Conclusion. In his book Tuesdays with Morrie, Mitch Albom reveals the The Successful Professor™ effect great teachers have on students. His personal experience with his teacher was lifechanging. Remember the first class you taught? Remember the first lecture when you knew your students knew? Remember that feeling of unbelievable delight, and remember that’s why you choose to teach. For the sake of student learning, conquer the killjoys and reclaim the thrill of teaching. References Albom, Mitch. (1997). Tuesdays with Morrie: An old man, a young man, and life’s greatest lesson. New York: Doubleday. Allen, D. (2001). Getting things done: The art of stress-free productivity. New York: Penguin. Davis, M. Hooked on music. On Mac Davis: Very best and more [CD]. New York: PolyGram. Lunden, J. (2001). Wake-up calls. New York: McGraw-Hill. Palmer, P. J. (1998). The courage to teach: Exploring the inner landscape of a teacher’s life. San Francisco: JosseyBass. ••••••••••••••• December Commentary Larry D. Head, Assistant Professor of Aviation Technologies at Southern Illinois University at Carbondale, is the author of the December Commentary. The title of his article is “A Mechanic’s Call to Arms.” Integrating Theory and Concepts with Application in a Capstone Business Administration Course W. Kevin Baker, Ph.D. Associate Professor Business Administrations Roanoke College Salem, Virginia baker@roanoke.edu Introduction One of the most difficult obstacles to overcome in pedagogy is integrating application or real-world aspects into the student’s learning experience. Too often we are accused of residing in an “ivory tower” and teaching courses devoid of practical application. This accusation is especially true in capstone courses that virtually demand integrating the concepts with application—especially in Business Administration curricula. In 1994, I restructured our Business Policy (Strategic Management) course with the goal of making this class function as a major integrative course utilizing effective applications. The results derived from outcomes assessments have indicated outstanding success. Business Policy The course Business Policy serves as our capstone course for the Department, and one of the goals of the course is to have students incorporate the knowledge they have learned in the major into a coherent whole. An academic reality precipitated by the high degree of specialization today is that students tend to learn continued on pg. 4.......... VOLUME 1 • ISSUE 5 3 Capstone Business Administration Course continued from pg. 3........... the different subjects piecemeal in a core curriculum without comprehensive integration. The use of extensive applications in Business Policy would allow students to see the “big picture” in terms of the different subjects form and function as a coherent whole. An academic reality precipitated by the high degree of specialization today is that students tend to learn the different subjects piecemeal in a core curriculum without comprehensive integration. Students enter Business Policy possessing the compartmentalized knowledge gained from three years of Business courses in various disciplines. In the course, the students learn Strategic Management concepts to use as a framework to apply and integrate this knowledge. These concepts serve as the supporting structure to integrate the other disciplines the students earn in our Department, i.e., Accounting, HRM, Economics, Finance, etc. However, it became apparent that learning the way these disciplines work together would require extensive applications to take the knowledge from the abstract and make it more reality-based and tangible to the student. Team-Based Learning The first major component of the course is to have the class itself function in teams just as industry does. The students work in groups of four or five. The preference is for teams of five to facilitate decisionmaking. These student groups will mimic autonomous work teams. Given assignments with deadlines, the groups decide The Successful Professor™ on the appropriate methods and work scheduling to accomplish the task. They also received unplanned tasks, just as in industry, to allow them to refine their skills further in decision-making and scheduling. Working in these groups also serves to demonstrate group dynamics, leadership, and interpersonal/intragroup communication. Evaluations are important components for groups, and an industry standard 360degree evaluation process is used. The professor, Business Administration faculty, and leaders of the business community evaluate the group members. Additionally, the group also evaluate each other’s individual performance at the end of the course. Because the groups are autonomous, they may also decide to eliminate a non-performing member at any time during the semester. Effectively removing a person from the course is indeed a drastic measure that the group must justify and the professor must approve.This action provides an incentive for active participation and involvement by all team members. Policy Project A second major component used for learning application is called the “Policy Project.” The groups must construct all the plans contingent on starting a viable business entity. Not only do the students learn to apply all they have learned from their Business Administration education, but they also learn innovation and entrepreneurship. The plans must be very detailed, with all areas researched and documented. Faculty members and business leaders from each discipline in the Department set the minimum requirements for information needed to satisfy their areas. For example, the financial area may require five-year pro forma balance sheets and income statements, cash budgets, fiveyear statements of equity/debt structure, ratio analyses, breakeven calculations, start-up cost breakdowns, five-year capital VOLUME 1 • ISSUE 5 expenditures, etc. It is important to note that each item and figure in these required statements must be researched separately to construct the statements. These requirements have grown to be quite extensive and detailed and they ensure consistency among the business plans. Each group will conduct marketing research, analyze the data, and justify demand for its business. At the end of the semester, the business plans are presented formally to the faculty and community business leaders for reviewing and grading. Our alumni indicate that this project was their most significant learning experience even after completing graduate school. Several of these projects have been developed to be very successful business entities in our community. Case Analysis The third component is the use of extensive case analysis. Thorough and detailed cases are used that reflect reallife experiences of corporations. The cases cover a wide variety of industries and are inclusive of all functional areas within these firms. The key is the use of comprehensive cases that examine an organization in its totality. Students will learn how to identify problem areas within the myriad of information and antecedent conditions. The student teams approach continued on pg. 5......... 4 Capstone Business Administration Course continued from pg. 4........... the cases as consulting firms, analyzing the organizations and making their recommendations. There is, of course, no precise right or wrong answer, but the key is how the teams justify their decisions. The results are presented to the class where they are further challenged to support and justify their recommendations. It can be quite adversarial in nature at times, but this further emulates strategic business sessions and hones the student’s communication skills. Simulation The fourth key component is the use of a business simulation. The simulation in this case allows the students to manage their own regional commuter airline. The realistic simulation is very detailed and designed by airline executives. All the classes compete against one another on the simulation, and their stock prices are graphed and posted in the classroom weekly. Each week represents a quarter of the year, and the simulation lasts 10 weeks (21⁄2 years’ simulation time). Groups that exceed a specified stock price barrier are included in the simulation “hall of fame” permanently—an achievement they perceive as quite an honor. To add to the sense of history of the simulation, every semester an alumni group will also compete against the students. This challenge is quite competitive and a great learning experience, not only for strategy but also group dynamics. In addition, teams will construct key business components for their airline, such as a mission statement, a marketing plan, and HRM components as major assignments. Grading Grades for the course are composed of both team grades (cases, project, and simulation) and individual grades (mid- The Successful Professor™ term and final examinations). All team grades are weighted by contribution as assessed by the group members at the end of the semester. For example, if a team member is judged by his or her teammates as contributing to only 90% of the completed work, then all this person’s team grades are multiplied by this percentage to derive group grades. Outcomes Assessment I am very proud of the results and the profound impact Business Policy has had in the Department and especially for our students. In exit surveys, we ask the students to indicate the most valuable courses in our Department. For the past seven years, Business Policy has been named as our most valuable course by an exceptional margin. In the latest surveys, Business Policy was mentioned by 100 % of the students as our most valuable course. For the past seven years, Business Policy has been named as our most valuable course by an exceptional margin. It is important to note that Business Policy was rarely mentioned at all as the most valuable course in the 1993-1994 exit surveys before the restructuring. Additionally, students rate all our courses on a seven-point scale from 1 (least valuable) to 7 (most valuable). Business Policy’s impressive rating of 6.99 was by a significant margin the highest rated course in the Department. The course has evolved to become the distinctive competency for our Department that generates much publicity for our college. ••••••••••••••• VOLUME 1 • ISSUE 5 Teaching Our Students the Language of Scholarship Robert W. Barnett Associate Professor of Composition and Rhetoric Director of the Writing Center The University of Michigan-Flint rbarnett@umflint.edu Philip T. Greenfield Lecturer, Composition Mott Community College Flint, Michigan pgreenfi@edtech.mcc.edu Introduction In a 1998 Language Arts Journal of Michigan article, “Bringing Theory, Practice, and Reality Together in the Teacher-Training Classroom,” Robert W. Barnett argues that “. . . good classroom practice is informed by a solid understanding of theory and that we as educators have a responsibility to incorporate this concept into the training of our students, many of whom will eventually become teachers themselves” (60). He goes on to illustrate how we can help students learn about our profession by immersing them in the very discussions and writing projects that define us as professionals in our field. Barnett uses the Theory into Practice Project (TIPP) as his model, a nontraditional research project that allows students to think as professionals by engaging other professionals in focused topics through their established scholarships. In a theoretical section of the project, the articles that students read become voices in a dialogue led by a student. In a practical section, students learn the importance of cementing that dialogue in application. In the end, continued on pg. 6.......... 5 Teaching the Language of Scholarship continued from pg. 5........... students learn the significance of incorporating sources to support their own views. More important, perhaps, students begin learning the craft that will contribute to their becoming scholars. Barnett’s initial aim of the TIPP was to introduce students to and engage them in the discourse of our discipline. As future members of a specialized community with its own specialized language, students should be given as many chances as possible to practice and learn the language. And because a good deal of the language of our field is embedded in our scholarship, we should focus some of our teaching on the language of our scholarship. By challenging them to think beyond traditional presentations of research and writing, we can help students more effectively apply their own experiences to their emerging knowledge of our field. In this article, we will further Barnett’s discussion of the TIPP by offering it as a model for teaching students the content and language that defines our field. For students to actively participate in our professional dialogues, we need to teach them the importance of (1) thoroughly understanding and problematizing an issue or idea, (2) synthesizing existing viewpoints, and (3) creating practical classroom applications. In short, by teaching students to learn the language of scholarship, to think and write as scholars, we are asking them not only to think and speak in theoretical and philosophical ways but also to react to the ideas that they are creating, to apply their knowledge to real life situations. The TIPP Introduction: Problematizing the Issue The opening of the TIPP represents an immediate departure from the traditional research paper, the introduction of which usually produces vague, formulaic, and The Successful Professor™ elusive statements that rarely contribute much intellectual thought to the paper. How many times have we seen papers open with statements like, “The topic of tutoring learning disabled students is very controversial,” or “A lot of factors contributed to the fall of classical rhetoric.” Eventually, a thesis emerges, but the old five-paragraph essay style seems to muffle the richness of a fully presented issue. The problem, in part, is that we ask students to make short, declarative thesis statements in a mere sentence or two when, in fact, we should encourage them to do what established writers do: pose many questions for themselves about the topic. In a 10-15 page TIPP, students usually take one and a half to two pages to introduce the topic. The answers, complications, and/or implications associated with their questions surely help them move closer to the heart of the issue. In this way, the TIPP introduction liberates students from the constraints of declarative writing and encourages them to write in response to questions they create for themselves and for their audience. Instead of padding a lengthy thesis statement with jargon, the TIPP introduction allows students to think through a topic and to make some sense of it for themselves. A short list of questions may easily be inserted into the TIPP assignment sheet to start students thinking beyond the micromanagement of a topic and on to a point where they can more clearly develop ideas that will sustain the paper. Questions like, “Why is this topic important to practitioners in your field? What are the implications of this topic on student learning? or Why is this topic significant to you? will stimulate much more critical thought, and thus more intellectually informed prose. By the end of the introductory section of the TIPP, the reader should notice a clear thesis emerging, accompanied by a clear sense of voice—two cornerstones of good scholarship. VOLUME 1 • ISSUE 5 The TIPP Theory: Synthesizing Existing Viewpoints The second section of the TIPP is also unique because it asks student writers to facilitate and contribute to a professional discussion as a way of further exploring, clarifying, and advancing the topic. Students cannot merely regurgitate information found in their source material. Rather, they must “find what others have to say about the topic, to analyze those opinions, to compare them to each other, and finally to blend those views with their own argument” (62). The emerging voice of authority that began in the opening section is allowed to continue here. The writer is given control of the discussion and becomes responsible for deepening the reader’s understanding of the topic by articulating the views of her sources at the same time she articulates her own. The underlying value in this approach is that students begin moving away from a style of writing that traps them into supporting what the professionals have to say at the expense of their own views. In the language of good scholarship, the writer is well supported by source material, not eclipsed by it. As teachers and professional writers, we too infrequently model good scholarly techniques for our students or engage them in discussions that reveal rhetorical markers indicative of good academic prose. Perhaps doing so will help our student writers take the control necessary to present new and interesting issues of their own to contribute to the developing scholarship of our fields. In the language of good scholarship, the writer is well supported by source material, not eclipsed by it. continued on pg. 7......... 6 Teaching the Language of Scholarship continued from pg. 6........... The TIPP Practice: Creating Application The final practice section of the TIPP best exemplifies the language of scholarship because it teaches students what we as scholars already know: that good theory is informed by good practice. In the classroom, we are most effective when we engage students in meaningful activities which have grown out of good theories. And students begin to make connections in their writing between theory and practice, as Barnett illustrates in the following observation of one of his own students: “[Eliot’s] topic was the noise factor in the campus Writing Center. After researching and analyzing the problems associated with the noise factor, Eliot concluded that we should reconfigure our Writing Center, with more space, to accommodate both open and private tutoring. After a discussion and rationale for the change, he drew a new floor plan for the Center”(63). Eliot had already begun thinking as a scholar by analyzing and researching noise and its effect on student learning. And to that extent, he entered the language of scholarship by articulating those aspects with language he had learned from other established scholars. But had he ended with only that argument, as the traditional research paper might ask, he would have been forgetting the actual problem. He was not simply looking at noise for noise’s sake; he was addressing a crucial concern. And he offered a viable solution to the problem he posed by creating a practical plan that would reduce the noise factor. Scholarship, similarly, begins with a problem, a question to be answered. “How do we bring down the noise that is currently permeating our Writing Center?” To become satisfied with theory alone is to leave the question unanswered, in essence stopping The Successful Professor™ the language of scholarship in mid-sentence. The TIPP’s practical portion finishes the sentence and answers the question. Furthermore, the setup of rationale, detailed explanation of how the project is carried out, and visual representation of the project, which the practice section calls for, fosters further critical thinking in students by urging them to provide detail and pragmatics as a part of their practical applications. Summary When we provide frequent opportunities for our students to problematize, to synthesize, and to ask intelligent questions as they write and when we use our professional dialogues as models for them to emulate, we are exposing them to the theory and the practice of our field. And when we fully immerse students in our discourse community through research, writing, and discussion—we can be sure we are teaching them the language of our scholarship. The TIPP may not offer a template for professional writing, but it will help open the door for students’ developing understanding of our language, helping them develop the critical skills necessary to become good scholars. Once they begin mastering those skills, they will better understand what it means to be a scholar, and their writing will begin to take on the same characteristics that make up the language of our scholarship. Reference Barnett, Robert W. “Bringing Theory, Practice, and Reality to the Teacher Training Classroom.” Language Arts Journal of Michigan Vol. 13.1 (Spring 1997), 60-63. ••••••••••••••• Generating Effective In-Class Discussions Calvin S. Kalman, Ph.D. Department of Physics and Centre for the Study of Learning and Performance Concordia University Montreal, QC, Canada H3G 1M8 KALMAN@VAX2.CONCORDIA.CA How can you have a really meaningful discussion in class? You want the discussion to be primarily student-based with you the instructor acting primarily as chair and resource person. Your intentions maybe to • • • breakup your lectures when students’ attention begins to wander, examine in-depth salient points in the course, and permit students to construct their own knowledge throughout the entire course. Each discussion is to be on a short topic (pericope) that you can place on a single sheet of paper or transparency. You want the students to engage metacognitively with this material, share their thoughts with a neighbour, and then open the discussion to the whole class. All of this is achieved using reflective-writepair share (Kalman,1999). The first step is for the students to read the pericope, and if desirable (from the students’ point of view), write notes or summarize the contents. Next they use reflective writing for a short, fixed time to examine its conceptual underpinnings of the material. My introductory calculus-based mechanics course begins with a description continued on pg. 8.......... VOLUME 1 • ISSUE 5 7 In-Class Discussions continued from pg. 7........... of nature in terms of displacement, instantaneous velocity, and acceleration. During each of the first three weeks, I use one reflective-write-pair-share activity to explore these concepts. In the first week, I use it so that students are to see that v=0 at one particular time does not imply that the body is stopped and in the second week so that students are to see that a=0 at one particular time does not imply that a body has constant velocity. The third intervention uses a reflective-write-pair-share exercise to contrast Galileo’s views with Aristotle’s about bodies falling near the earth’s surface in a vacuum. It is pointed out that Aristotle is against idealizations. Since a vacuum does not exist, according to Aristotle, the speed of a body in a vacuum should not be considered. Students are introduced to Galileo’s viewpoint that it is useful to consider idealizations of phenomenon occurring in the real world. Reflective Writing Reflective writing is based upon the notion of “freewriting” popularized by Peter Elbow (1973). J. Countryman defines freewriting as writing rapidly for a short and fixed period of time (1992, p. 14). Freewriting falls within J. Britton’s notion of expressive writing (Britton et. al. 1975). Britton uses the term expressive writing to refer to writing to oneself—as in diaries, journals and first-draft papers—or to trusted people who are very close to the writer, as in personal letters. Because expressive writing is not intended for external audiences, it has few of the constraints of form and style. Expressive writing often looks like speech written down; usually it is characterized by first-person pronouns, informal style, and colloquial diction. Toby Fulwiler (1987) comments that “some writing activities promote independent thought more than others do. Expressive The Successful Professor™ or self-sponsored writing, for example, seems to advance thought further than note copying” (p. 21). Many examples of such writing are found in the works of Fulwiler. In particular, Verner Jensen proposes a section in “Writing in College Physics” that “understanding can be enhanced through a free-writing experience . . . Physics students can use the writing process to clarify their thinking and understandings about physical phenomena through their written articulation of relationships. Learning physics requires many different mind processes, including abstract thinking. Writing can assist the student with this process” (p. 330). In general the use of writing in science and mathematics has been to have students examine material after it has been discussed in class. See D. K. Pugalee (1997), for example, who reviews the various uses of writing in the teaching of mathematics. Freewriting has also been used as a way for students to pinpoint their difficulties in solving quantitative problems (Countryman, 1992, Mayer & Hillman, 1996, Kalman, 2001). Previous research on freewriting has been done in multiple subjects and levels of formal schooling (Countryman, 1992, Kalman & Kalman, 1996, Goldberg & Bendall, 1995). These studies have typically included freewriting as a learning intervention treatment in a quasi-experimental study. From the results of these studies, there is evidence that freewriting enhances the elaboration of subject matter concepts through writing. The term reflective writing is used to refer to the use of freewriting to interact with material in a manner that includes self-monitoring of the understanding of the conceptual underpinnings of each reading. My student Nabilla put it this way: “If there’s a new concept, you’re trying to understand what is it about . . . and that’s what you freewrite about, what you think about the new concept, and how does it make sense to you.” The instructions VOLUME 1 • ISSUE 5 for reflective writing: Think carefully about the material presented to you. If you normally write notes on material you read, do this at the same time. Then write freely about the material. “Write freely” includes the following points adapted from Elbow’s work (1973): “Just write and keep writing. Talk to yourself in your writing” (p. 61). “If you stop involuntarily in the middle of a sentence, force yourself to keep writing and write to yourself whatever it is you have to say about that sentence: why it is stupid or wrong, how you noticed it, whatever” (p. 74). Along these lines, my student Solomon notes that “typically I’d write. I don’t understand this concept, what does it have to do with anything, and then well, I guess maybe it works this way or that way and I’ll actually ask myself questions about the material . . . for more clarification; typically it’s because I don’t understand a link . . . how two things fit in the puzzle.” Another student, Alexei, stated that “it’s a little bit like thinking out loud and then putting it on paper; so it’s pretty much like what I always used to do; it’s just that it’s quite surprising to see how much more it’s helpful once it’s put down on paper . . . it’s also helpful because even if I don’t find the answers at least I will find the questions. If there is something I don’t understand, or if there’s a popular concept I find difficult, at least I can find why I don’t understand it even if I won’t understand it, or like not right now, but at least I’ll be able to find the questions. Sometimes I find that is the first step . . . so in order to find the answers you need to find the right questions.” After completing their reflective writing on the pericope, students share their ideas with their neighbours, and then the discussion is opened up to the entire class. continued on pg. 9.......... 8 In-Class Discussions continued from pg. 8........... References Britton, J. et. al. (1975). The development of writing abilities 11 - 18. (London: Macmillan). Countryman, J. (1992). Writing to learn mathematics: Strategies that work. (Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann). Elbow, P. (1973).Writing without teachers. (New York, NY: Oxford University Press). Fulwiler, T. (1987). The Journal Book. (Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann). Fulwiler , T. “Writing an Act of Cognition” In C. W. Griffin (ED.) New Directions for Teaching and Learning:Teaching Writing in all Disciplines, no. 12. San Francisco: Jossey Bass, Dec. 1982. Goldberg, F. and Bendall, S. (1995). “Making the Invisible visible: A teaching/learning environment that builds on a new view of the physics learner.” American Journal of Physics 63, 978-990. Jensen, Verner. “Writing in College Physics.” section 35 pp 330-336 in Fulwiler, T. (1987). The Journal Book. Portsmouth, NH:Heinemann. Kalman, J. and Kalman, C. (1996). “Writing to learn.” American Journal of Physics 64, 954- 955. Kalman, C. S. (1999). “Teaching science to non-science students using a student-centred classroom.” In K. Ahmet and S. Fallows (Eds.), Inspiring students: Case studies in motivating the learner (pp. 17-24).(London, England: SEDA: Staff and Educational Development Series Kogan Page Limited.) Kalman, C. S. (2001). “Teaching Students to Solve Quantitative Problems in Science Courses by Writing Their Way into the Solution. The Successful Professor. Sample Issue, 3-4. Mayer, J. & Hillman, S. (1996), “Assessing Students’ Thinking through Writing.” The Mathematics Teacher 89,428-432. Pugalee, D. K. (1997). Connecting Writing to the Mathematics Curriculum. The Mathematics Teacher 90, 308-310. ••••••••••••••• The Successful Professor™ Motivating Students to Achieve: Six Strategies for Success Nichola D. Gutgold, Ph.D. Assistant Professor of Speech Communication Penn State Berks-Lehigh Valley College Fogelsville, Pennsylvania dgn2@psu.edu As professors, one of our main objectives in the classroom is to motivate students. We have all had students that seem to lack the energy commitment to perform well in class, so motivating them could mean the difference between success and failure. But how can we motivate? What can we do to make our students want to do well? Most of us can think of some theories of motivation – B.F. Skinner, the Hawthorne Studies, Abraham Maslow, and others. But the question is, are we, as professors, motivated to motivate our students? Although motivation comes from within, in other words, people motivate themselves, we as professors can create a communication climate in our courses for students to motivate themselves. What follows are six principles for motivating others put forth by Professor Mel Silberman in his Training and Performance Sourcebook. I have adapted those principles for use in our classrooms. These are ways we can enliven our courses with positive energy and encourage our students to do what they should to learn and succeed! Six Principles For Motivating Students 1. Positive Thoughts Motivate. What conditions motivate people? Recall the teacher, friend or parent who motivated you to do well by telling you that you could succeed. This is an example of our VOLUME 1 • ISSUE 5 first principle of motivation: Positive thoughts motivate. In Your Class: Try to identify the strengths in your students and encourage them to pursue academic goals that match their strengths and interests. I teach communication skills, and one very motivating factor in my class is I give students credit for what that they are already doing well. My doing so takes practice, but the payoff is big. Students will appreciate your thinking about their specific strengths and your noticing them. Try to identify the strengths in your students and encourage them to pursue academic goals that match their strengths and interests. 2. Enjoyment Motivates. Maybe you can remember a time when doing something fun made you continue. Recall an exercise program or a research project that, for example, took on a life of its own and provided you with much pleasure. In Your Class: Lighten up a little and introduce students to the idea that learning can really be fun. Have mini speaking contests through-out the semester: give away candy bars or other small tokens to show that there is a prize for winning, and let students be the judges. Take students on as many out-of-class experiences that time and budget allow. Bring in guest speakers. These are all ways to enliven the learning and make it enjoyable to the students. 3. Feeling Important Motivates. Do you remember a time when your opinions were sought? Have you ever been invited to contribute an article or make a presentation? I bet it motivated you! continued on pg. 10.......... 9 Motivating Students continued from pg. 9........... In Your Class: Empower students to shape the course. As the course progresses, assess the course. Give little surveys. Ask students to help create assignments and tests. Ask students to offer their opinions about what makes a good professor or learning environment. Show students that you take their advice by putting their reasonable requests into practice in your class. Do you remember your BEST teachers? They were the ones who taught with you constantly in mind. They tailored the course to meet the needs of each specific class. 4. Success Motivates. For many people motivation occurs when they do something well. You feel part of a worthwhile endeavor and you work hard to ensure continued success. The saying is true: nothing succeeds like success! In Your Class: Give credit for little victories. In public speaking class, little victories can be found for a student who was too afraid to speak, who managed to speak to a small group, to the skilled speaker refining transition statements in a speech. The key here is that success is very specific to the individuals in the class. 5 Personal Benefits Motivate. What’s in it for me? Most people want to know the answer up front. Many people need to see the reward system before they can get excited about performing well. In Your Class: Be very clear about your grading and the penalties for not completing assignments. This is a hallmark of good teaching. In speech class, I show sample speeches that are “A” “B” and “C” grade speeches. I give a very detailed description of how they are graded. I also make the statement in the first class: “This course is designed for you to succeed.” This sets the tone and lets students know that their destiny is in their own hands. The Successful Professor™ Many people need to see the reward system before they can get excited about performing well. 6. Clarity Motivates. If our task is unclear, we cannot know what we need to do to be successful. This point is a close cousin to #5, because being clear―letting people know what they need to do to be successful—usually makes people very successful. In Your Class: Spell out your goals and expectations for students as clearly as you can. Bring in sample work from the previous year and describe projects in great detail. Give specific information about formatting, length, and due dates. The clearer you are, the more students will be able to live up to your clear expectations. Remember that lifting up students is a sure-fire way to make your courses more effective, your time better spent, and your teaching more successful. Reference Silberman, Mel. (Ed.). (1999). “How to motivate others.” Training and Performance Sourcebook. New York: McGraw-Hill. ••••••••••••••• The Story of Your Name Kim Cuny Director of The Storytelling Project Department of Communication Monmouth University West Long Branch, New Jersey kcuny@yahoo.com Introduction For ten years I started each class off with the same ice breaking “circle of friends” activity because the students liked it and it accomplished the desired goals. After team teaching The Power of Story at Monmouth University for a year with Claire B. Johnson, I was challenged to come up with an even better ice breaker. Claire encouraged me to find a way that the first day ice breaker might also serve as an introduction to the performance elements that I would later cover in great detail. What resulted is a class activity which fosters a sense of community, allows students to face their communication apprehension in a non-threatening way, introduces some of the performance elements of speaking (eye contact, rate, and volume), and creates a positive atmosphere in which the rest of the semester can flourish. This activity can be beneficial to anyone who teaches classes which require student presentations, discussion, in-class activities, or other forms of oral communication. Beyond my Children at Atlantic Highlands Elementary School in New Jersey enjoy a story about a man who needs a hearing aid. (Credit for the photograph goes to Jim Reme.) continued on pg. 11.......... VOLUME 1 • ISSUE 5 10 The Story of Your Name possible. Make it clear that only one person should be talking at any point in each group. communication courses, I have used it in my interdisciplinary class and in workshops with 4th-6th graders with great success. 4. After all students have had the chance to share their story with their group of four, create groups of eight (again in circles) by joining two groups of four. Have them take turns telling the story of their name until all eight people in the group have had the opportunity to speak. No reading once again. Make it clear that only one person should be talking at any point in each group. continued from pg. 10.......... What to do before the activity: Be sure your class has been assigned to a room which will allow for chairs and desks to be moved. Students will need to move their seats as the activity progresses. Students will stay seated during the entire activity. This activity can be beneficial to anyone who teaches classes which require student presentation, discussion, in-class activities, or other forms of oral communication. What to do during the activity: 1. Instruct students to write down the story of their name. Tell them to be sure to include everything they know relating to their name. This might include the reason they were so named and/or anything that has happened to them to date related to their name. From this point on, all members of the class will participate in each step of this activity at the same time. (It will get loud at times.). 2. Pair students up in teams of two and have them read their name stories to each other. 3. After all students have had the chance to share their story with a partner, pair teams of two together forming circles made up of groups of four students. Have them take turns telling the story of their name until all four people in the group have had the opportunity to speak. This time tell them not to read but instead look at the others in the group as much as The Successful Professor™ the content of the course. I like to follow my review of the syllabus with this activity. I have sometimes facilitated the discussion on the second day due to time restrictions. At the end of each semester when students are asked to reflect on their progress for the semester, they often point to the name story activity as the reason they were able to start out so successfully. One former student, now studying education in graduate school, recently commented on the power of story to transform the classroom on that very first day of the semester. 5. After all of the groups of eight have finished, split the class into two large circles. Have the students take turns telling the story of their name until all in the circle have spoken. No reading. Make it clear that only one person should be talking at any point in each group. 6. The last step involves the entire class forming one large circle. One at a time individuals, including the faculty members tell the story of their names to the entire class. No reading. What to do after the activity: Facilitate a discussion or assign a written reflection which focuses on any of the following: • What are the common themes heard in the stories? • What are personal adjustments made in presenting the story as the audience grew? • What changes did they notice in the stories of others as they were repeated? • What are the benefits of practicing a public address before the formal presentation? • What might someone have learned as a result of participating in the activity? Monmouth storyteller Stephen Bridgemohan tells students at Bradley Primary School in Asbury Park, NewJersey about his proud heritage through the story of his name. ••••••••••••••• Kim serves on the Communicating Common Ground (CCG) national leadership team. CCG (http://www.natcom.org/Instruction/ CCG/ccg.htm) is a partnership of the National Communication Association, American Association of Higher Education, Southern Poverty Law Center, and Campus Compact which is dedicated to stopping hate, hate speech, and hate crimes by teaching tolerance to kids. To find out more about The Storytelling Project visit www.monmouth.edu/~story. Conclusion The questions used after the activity can be designed to focus on the specifics of VOLUME 1 • ISSUE 5 11 Meet the Authors Deborah Frazier has been employed with the University of Arkansas Community College at Batesville since 1987. She has served as an instructor; lead faculty; chair for the Division of Business, Technology and Public Service; and is currently Vice Chancellor for Academic Affairs. She is a past UACCB Outstanding Faculty Award winner and Faculty Senate President. Ms. Frazier’s community service includes tenures on the United Way Board, the Independence County Fair Board, Christmas Brings Hope, Children of North Central Arkansas, and Midland School Board. She is currently a candidate in the Doctoral of Higher Education program at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock. Jennifer Methvin, an English instructor at the University of Arkansas Community College at Batesville, has been teaching English in Arkansas two-year colleges for over ten years. She teaches basic writing, freshman composition, technical writing, creative writing and world literature courses. Methvin holds a B.F.A. in Creative Writing from Arkansas Tech University and an M.A. in English from Oklahoma State University. In 1997 and 1999, she received an Arkansas Association of Two-Year College Outstanding Faculty Award. Currently she serves on the Board of Directors of the Ozark Foothills FilmFest and is the Past-President of the Arkansas Association of Two-Year Colleges. W. Kevin Baker, Ph.D., has taught in the Business Administration Department at Roanoke College for the past 9 years. He has 18 years of overall of teaching experience at both the graduate and undergraduate levels. He earned his doctorate from the Pamplin School of Business at Virginia Tech. He teaches the capstone course of Business Policy for the Department. His research interests include affective responses to the workplace/classroom and organization culture. Robert W. Barnett has published in the areas of WAC, writing centers and composition studies. His most recent book is titled The Allyn & Bacon Guide to Writing Center Theory and Practice. He is currently working on a new manuscript, Centering Basic Writers: A Writing Center Based Approach. He lives in Flint, Michigan, with his partner Philip. Philip T. Greenfield has worked in writing centers, developmental writing, Internet writing, and corporate writing. His research includes writing in mathematics and composition on the Internet. He currently teaches freshman composition and business technical writing at Mott Community College. He lives in Flint, Michigan, with his partner Bob. The Successful Professor™ VOLUME 1 • ISSUE 5 12 Meet the Authors Dr. Calvin S. Kalman is professor of physics at Concordia University in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. He is a Fellow of the Science College and a member of the Centre for the Study of Learning and Performance. He earned his doctorate from the University of Rochester. In 1980, he received the Concordia Unversity Council of Student Life Teaching Award and, in 1999, the Canadian Association of Physicists Medal for Excellence in Teaching. In addition to publishing in his field, he has refereed for numerous journals of physics. Nichola D. Gutgold, Ph.D. is an assistant professor of speech communication at Penn State Berks-Lehigh Valley College. Her work includes pedagogy related to teaching public speaking and rhetoric of women. Her recent projects include a book on the rhetoric of Elizabeth Dole and a chapter on the rhetoric of Betty Ford. An active consultant, she enjoys teaching public speaking, professional and organizational communication, and negotiation skills. Kim Cuny is the Director of The Storytelling Project within the Department of Communication at Monmouth University. Kim’s dedication to teaching and learning were first recognized in 1998 when she received a Teaching Excellence Award in North Carolina. Regularly featured in Teaching Ideas for the Basic Communication Course, Kim is responsible for the new tradition of featuring Great Ideas for Teaching Speech/Communication (G.I.F.T.S.) sessions at the annual communication conferences in both New Jersey and the Carolinas. (Credit for the photograph goes to Jim Reme.) The Successful Professor™ VOLUME 1 • ISSUE 5 13