A Q U AT I C I N... A handbook for education efforts Written by: Mandy Beall Autumn 2005

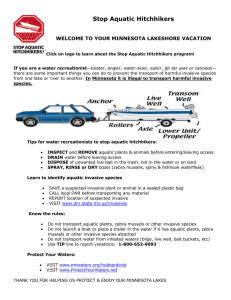

advertisement