Erethizon dorsatum Porcupine

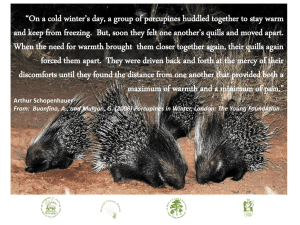

advertisement

Rebecca Clarke Erethizon dorsatum Porcupine Description: Erethizon dorsatum (the common porcupine) is near the high end of the rodent bodyweight spectum. In North America, only Castor canadensis surpasses it (Roze 1989). It has a large chunky body with a high arching back, small head, short legs, and short thick tail (National Wildlife Federation 2002 http://www.enature.com). Upwards of 30,000 quills cover every part of the body except the under-parts, muzzle, and the ears (Woods 1973). Quills are modified guard hairs measuring up to 75 mm long and 2 mm wide. The longest quills on a mature porcupine are located on the rump and may measure up to 10 cm in length. The shafts are white and the tips are black. The tips of the quills carry microscopic downward pointing barbs (Roze 1989). The feet are naked and modified for arboreal life. The incisors are heavy and deep orange (Ward 2003 http://www.scz.org/animals/p/prcpine.html). The dental formula is: inscisors 1/1, canines 0/0, premolars 1/1, and molars 3/3 = 20 teeth. Their rooted cheek teeth have occlusal patterns dominated by re-entrant enamel folds. The skull is robust and the rostrum is deep (Legras 1998 http://www.chez.com/rodent/Erethizontidae/Erethizontidae.html#F). External measurements: Weight, 5-14 kg (males) total length, 808 mm; tail, 235 mm; hind foot, 98 mm; (females) 737-230-81 mm. (Texas Parks and Wildlife Department 1994 http://www.nsrl.ttu.edu/tmot1/eretdors.htm). Distribution: E. dorsatum inhabits much of North America between the Arctic Ocean and Northern Mexico (Kurta 1995). In the east they occur in the New England states, New York, Pennsylvania, Michigan and Wisconsin (Woods 1973). They live in the northern twothirds of Wisconsin in a territory that extends in a V-shape from about the Ellsworth area in Peirce county down to Wisconsin Dells and back up toward Green Bay (Martin 2003 http://www.wnrmag.com/stories/1996/feb96/rodent.htm). It has been exterminated form the southern areas of the state because the land is now dominated by farmland. In the north it lives in deciduous and coniferous woodlands. Erethizontidaie has a long fossil history dating back more than 30 million years to the Oligocene epoch. The family originated in South America and slowly spread northward during the Pliocene epoch. Today most species still live in Central and South America (Kurta 1995). Reproduction: Breeding in E. dorsatum occurs in the fall and early winter. Female porcupines reach sexual maturity at about 18 months old. The estrous cycle is 29 days, and they have more than one period of estrus in a year. They are in heat for a period of 8 to 12 hours (Legras 1998). As a female approaches her estrus the membrane that had obstructed the vaginal orifice weakens and dissolves. The vagina begins to secrete a thick mucus, serving as an olfactory cue for males (Roze 1989). An elaborate courtship takes place that includes grunts, and whines a “dance”, and the male showering the female with urine (Kurta 1995). During the mating season, males wander more widely than in the months before. Mating success in males is positively correlated with weight and size of his non-winter territory. It is possible that a single dominant male may inseminate all the females within his home range. Females will form a copulation plug after mating has occurred. Essentially every female bears one young per year (Roze 1989). The gestation period averages 210 days with the young born in April-June. The average weight of the precocial newborn is 21 ounces. Young display typical defense reactions within a few days. Infant mortality is very low and mothers will remain with their young for up to six months. Porcupines grow for three or four years before they reach adult body size (Legras 1998). ECOLOGY Diet: E. dorsatum is a renowned feeding generalist exhibiting seasonal shifts in diet (Snyder and Linhart 1997). During the summer and spring they feed extensively on leaves and ground vegetation. Over winter they feed on the cambrium, phloem, and foliage of a variety of woody shrubs, and deciduous and coniferous trees (Zimmerling and Croft 2001). The minimum protein requirement for rodents is 15% nitrogen and low levels of nitrogen or crude protein in porcupine winter diets result in mass loss as fat deposits are utilized as a dietary supplement. Porcupines undergo severe nutritional stress in late winter (Sweitzer 1996). Porcupine feeding damage has been identified as a serious threat to survival and growth of conifers in some areas. Utah- Pinus contorta, MinnesotaPinus sylvestris, Oregon, South Dakota, and Wyoming- Pinus ponderosa, Alaska- Picea sitchensis, and Tsuga heterophylla (Zimmerling and Croft 2001). Salt is often intensively sought after by E. dorsatum and they will gnaw on antlers and bones when found (Nowak 1983). They are semi-arboreal and spend much of their time in trees (Roze 1989). Summer home ranges average 14 hectares, winter home ranges are smaller averaging 5 hectares. They den in rock crevices or hollow trees (Pittman 2001 http://www.ku.edu/~mammals/erethizon.html). Behavior: Porcupines are primarily nocturnal. They don’t hibernate but spend much of their time in dens during the winter. Although porcupines are basically solitary, several will share the same den during the winter (Pittman 2001). Predation and Defense: E. dorsatum is the only mammal in North America that uses quills to deter predators (Sweitzer 1996). Porcupines will evade predators by arching their back to expose their barbed spines, and drawing their head partly under their body or forcing it into a protected area. If a predator encounters E. dorsatum, it will forcefully slap its tail against the head of the predator, firmly imbedding the spines in the face, lips, and mouth. Quills are not thrown but instead easily detach from the porcupines body (Pittman 2002). Martes pennanti, though a much smaller carnivore, is the most effective predator of E. dorsatum. It kills by attacking the quill-less face. They can then turn the porcupine over and begin feeding on its ventral surface. Another important predator is Felis concolor. Minor predators include Lynz canadensis, Lynz rufus, Canis latrans, Bubo virginianus, Canis lupus, Gulo gulo (Roze 1989). Remarks: Native Americans used the quills of E. dorsatum for embroidery, baskets, and artwork (Marin 2003). Today, in many areas of North America where logging is a major industry, the winter-feeding habits of the common porcupine bring the animal into direct conflict with the forest industry because of damage caused by foraging (Zimmerling and Croft 2001). References: eNature.com Inc. 2003. Common porcupine. http://www.enature.com Accessed 2 Dec 2003. Kurta, A. 1995. Mammals of great lakes region. The University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA. Legras, M. 1998. Erethizon dorsatum. <http://www.chez.com/rodent/Erethizontidae/Erethizontidae.html#B>. Accessed 28 Nov 2003. Martin, D. A. 2003 Dec. Wisconsin’s prickly rodent, Wisconsin natural resource magazine 1996. <http://www.wnrmag.com/stories/1996/feb96/rodent.htm>. Accessed 27 Nov 2003. Nowak, R.M. 1991. Walker’s Mammals of the World, 5th Edition, Vol. I. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, Maryland, USA. Pittman, G. 2002. Porcupine, Erethizon dorsatum bruneri Swenk. <http://www.ku.edu/~mammals/erethizon.html>. Accessed 1 Dec 2003. Roze, U. 1989. The North American porcupine. Smithsonian Inst. Press, Washington, D.C. USA. Snyder, A. M., and Y. B. Linhart. 1997. Porcupine feeding patterns: selectivity by a generalist herbivore. Canadian Journal of Zoology 75: 2107-2111. Sweitzer, A. R. 1996. Predation or starvation: consequences of foraging decisions by porcupines (Erethizon dorsatum). Journal of Mammalogy 77(4): 1068- 1077. Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. 1994. Porcupine, The mammals of Texas online edition. <http://www.nsrl.ttu.edu/tmot1/eretdors.htm>. Accessed 1 Dec 2003. Ward, B. 2003 Mar. Sedgvick county zoo, Erethizon dorsatum. <http://www.scz.org/animals/p/prcpine.html>. Accessed 2 Dec 2003. Woods, C. A. 1973. Erethizon dorsatum. Mammalian Species 29: 1-6. Zimmerling, N. T., C. D. Croft. 2001. Resource selection by porcupines: winter den site location and forage tree choices. Western Journal of Applied Forestry. 16(2): 53-63. Reference written by Rebecca Clarke, Biol 378: Edited by Chris Yahnke. Page last updated.