Tapirus terrestris Brazilian Tapir

advertisement

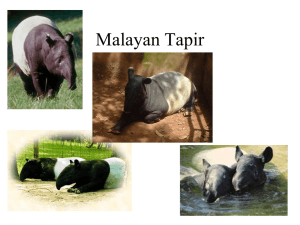

Tapirus terrestris Brazilian Tapir Physical Description Brazilian tapirs are large terrestrial mammals. Tapirs have short, robust bodies and are about the size of a pony. Adult tapirs are around 84-110 cm (19-45 in.) at their shoulder and from 227-363 kg (500-800 lbs.). In adult tapirs the body, head, and legs are a uniform blackish-brown color and the belly region is a lighter color. Young tapirs are dark with bright yellow or white longitudinal stripes alternating with lines of spots and a white belly. The skin of the tapir is grey and they are partially covered in a short, smooth hair. They also have a short, stiff mane of longer, darker hair that runs in a narrow stripe from the forehead to the shoulder. The distinctive nose and upper lip of the tapir form a trunk-like proboscis with transverse nostrils located at the tip. The eyes of the tapir are small and flush with the sides of the head. They have ears that are oval, erect, and not very mobile. The tips of the ears are also white. The tail of the tapir is just a short stump. The hind feet of the tapir have three toes and the forefeet have four toes. The Brazilian tapir has brachy-lophodont cheek teeth for grinding leaves. The typical dental formula for them is I3/3, C1/1, P4/3, M3/3 = 42 (Emmons, 1997). Distribution Brazilian tapirs are found in South America, east of the Andes Mountains from northern Columbia to southern Brazil and northern Argentina to Paraguay. They are found up to at least 2,200 meters in elevation (Emmons, 1997). Tapirs are found all through Paraguay. Ontogeny and Behavior The Brazilian tapir like most ungulates is herbivorous. They eat mostly water plants, leaves, buds, twigs, and fruits. The tapir has a simple digestive tract with an enlarged cecum where microorganisms live and digest the cellulose from the plants (Emmons, 1997). Since plants are not an extremely efficient source of energy the tapir needs to spend most of its day foraging for leaves in order to obtain adequate energy. Tapirs are mostly nocturnal but they are partly diurnal. They travel to watering areas to feed in the morning and evening. During the day they rest in thick vegetation, wade in the water, or wallow in the mud. Wallowing helps to rid themselves of parasites and pests (World Book, 1972). Tapirs are solitary, wary creatures; although, many tapirs live in the same area. They are shy and silent and are rarely seen in the wild. They are good runners, hillclimbers, sliders, waders, divers, and swimmers. When swimming they occasionally dive to the bottom to root and dig for water plants. Tapirs are generally silent but they do communicate with a loud whistle. They will also grunt or stamp their feet when they are alarmed. Usually when tapirs are alarmed they will run to the nearest water, dive in, and sink below the surface. If they have to tapirs will defend themselves by biting in a swine-like fashion (Anderson & Jones, 1967). The senses of hearing and smell are highly developed in tapirs. Their enemies include jaguars, pumas, and humans. Ecology and Reproduction Brazilian tapirs are found in rainforests, gallery forests, dry forests, the Chaco, and open grassy habitats with water and dense vegetation for refuge. They favor waterside habitats like swamps, river edges, and lush stream bottoms (Emmons, 1997). Mating takes place anytime of the year but is most common right before the rainy season. Gestation period is about 390 days but varies from 392-405 days (Anderson & Jones, 1967). Females most often give birth to one offspring every second year. They will rarely give birth to two offspring. The young tapirs are born with a dark coat patterned with yellow and white stripes and spots. This coloration makes the calves hard to see in leafy shadows. The calves keep this coloration for about six months. Calves stay with their mothers for six to eight months before living on their own. The average lifespan of the Brazilian tapir is about 25 years in captivity (National Geographic Book of Mammals, 1981). Remarks The Brazilian tapir is the only extant native New World odd-toed ungulate (Emmons, 1997). The tapir is locally common, but it is scarce in over-hunted regions. The meat of the tapir is prized and they are easy to locate with dogs or calls and are vulnerable to local extinction. As of 1983 the IUCN classifies Tapirus terrestris as an endangered species (Nowak & Paradiso, 1983). References Anderson, Sydney and J. Knox-Jones Jr. Recent Mammals of the World: A synopsis of families. The Ronald Press Company. New York. 1967. pp. 377-379. Emmons, Louise H. Neotropical Rainforest Mammals: A Field Guide. Second Edition. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago. 1997. pp.173-174. Nowak, Ronald M. and John L. Paradiso. Walker’s Mammals of the World Fourth Edition. The John’s Hopkins University Press. Baltimore. 1983. Vol. 2, pp.11631165. The World Book Encyclopedia. Field Enterprises Educational Corporation. Chicago. 1972. Vol.19. pp. 30-31 Reference written by Cori Ankenbrandt, Biology 378 (Mammalogy), University of Wisconsin – Stevens Point. Edited by Christopher Yahnke. Page last updated August 15, 2005